hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[K-pop: To Love or Let Go] The dark side of K-pop light sticks

Back when I was a fan of BTS, I used to have an Army Bomb, as the group’s official light sticks are called. Not just one, though, but three, and all in different versions.

I remember being so excited when I bought my first Army Bomb in 2015. I’d picked it up for my first pop idol concert, and back then, a light stick just felt like something you get to “cheer” for an idol. (Sidebar: that’s exactly what the Korean word for light stick, or eungwonbong, means: “cheering stick.”)

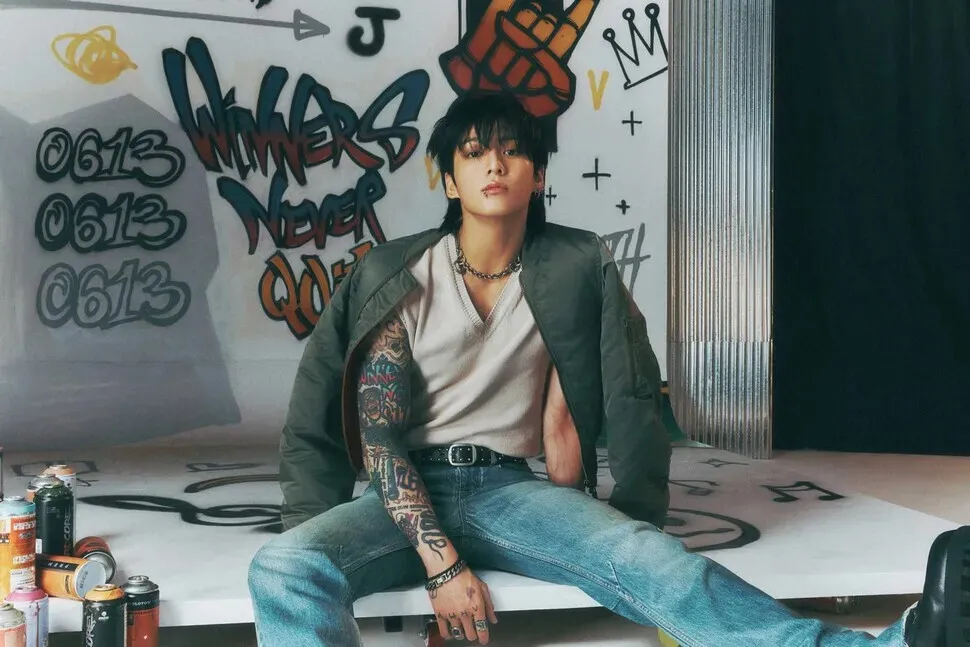

When I saw Jungkook, the youngest member of BTS, break into tears during his rendition of “Born Singer” at that concert, my whole body trembled with intense emotion. That was when my Army Bomb became something more than a piece of merchandise. It was a talisman that could evoke the concert hall and its atmosphere.

But when I purchased my second and third Army Bomb, I wasn’t as happy or as excited as before. The light stick I had before was in perfectly good condition, and I was pressured to drop it for the next version. It looked slightly different.

It also had a new function that I wasn’t exactly thrilled about. It was fitted with Bluetooth technology that allowed the lights to be controlled remotely during performances. Without even being given the option to reject, it’d become a part of my light stick. The function’s stated purpose was to create more spectacular concerts.

In concerts where I brought my second and third light sticks featuring this new function, I didn’t wave the light sticks as I did before. Rather, I just passively held it. The light stick was physically in my hand, but it didn’t feel real. Since the concert planners had control of its features, perhaps this was a given.

Moreover, I had to invest more labor and capital into the new light sticks. I had to switch the stick to the right mode before the concert, and throughout each concert, I’d constantly fret about the light stick maintaining power and brightness, so I’d inevitably have to purchase an extra set of batteries. The kicker is that if your light stick ever breaks, it’s not repairable.

Naturally, if I were dissatisfied with these drawbacks, I could have simply not purchased the new iterations. Or I could have shut off the Bluetooth mode that allows the concert coordinators to control the light stick. I could have “resisted” in such ways.

Superficially, it was all my choice. However, to be there in the crowd at a concert and not partake in rituals is considerably difficult. To use a dramatic word, resisting constitutes a “betrayal” of an unspoken promise between the idols and the fans. Just imagine: When all the light sticks in the stadium turn the color purple, which represents BTS and us fans known as “Army,” I’d be the only one not holding a light stick. Or mine would be the only light stick that’s shut off. Can you imagine how awkward that would be? How much I would stick out?

To some people, it’s probably no big deal. When you purchase light sticks and other merchandise as a K-pop fan, you pay the price to become the owner, which gives you the ultimate right over what you do with it. So in a way, it feels like your own “free choice.” However, that’s not the case.

In the case of light sticks, it’s the concert coordinators, not the purchaser (owner), who control them during concerts. This control is handed over without any compensation, which is highly unusual when compared to the ownership rights of other products.

Control over a product is normally transferred to the purchaser (owner) at the moment of purchase. To loan or transfer this control to another person, there needs to be a clear expression of intent. If control is taken without this clear expression of the owner’s intentions, we normally refer to such an act as “theft.”

These concepts of ownership and ownership rights, which have been foundational to our free-market society, are then erased through a “feature upgrade” and the pretext of “participating” in an idol concert. My capital and my labor were taken without a trace or sound and transferred to the very people who encouraged me to purchase the light stick. They even took capital and labor that I’d never explicitly thought of as mine.

The truth is, it’s not just about light sticks. Without being aware of it, the productivity of the K-pop fans is delicately straddling the line between voluntary fanhood and fan culture and the industry’s pressure on fans to purchase and consume. In the process, big business and capital is pillaging every little thing they can from fans.

As indicated by terms like “K-pop stan,” the longstanding stereotype about K-pop fans is that they’re irrational and they engage in unproductive and consumptive behavior. A lot of fandom researchers have tried to dispel this image.

According to the book “Understanding Fandom: An Introduction to the Study of Media Fan Culture,” by Mark Duffett, an associate professor of media studies at the University of Chester, this perception is based on a longstanding misunderstanding. Fandoms do not simply consume. The same goes for K-pop fandoms. Driven by their passion for someone, fans consistently make things, meet people, and form organizations and relations. What results is not only influence but an entirely new market and economy.

For instance, dolls based on idols were originally unofficial products made by fans, but now they’ve evolved into official merchandise. Since the second generation of K-pop idols, the industry has aggressively absorbed this type of fandom productivity to directly produce profit.

The same goes for the light sticks that were used in last year’s pro-impeachment demonstrations, which lit up to symbolize solidarity among the protesters. They, too, are fandom products that have been appropriated by the K-pop industry. When it came to the production or purchase of the balloons and placards that preceded the light sticks, the choice was more or less in the hands of the fans. Since then, the industry has solidified its fan management strategies and concepts of intellectual property. Now, the fan is entirely and aggressively managed by the industry.

Merchandise produced organically by the fans, as well as other forms of fan labor, have gradually been distorted into an unlicensed and “unofficial” production line belonging to the entertainment agencies. A border has started forming between official and unofficial. We are also seeing a gap between hierarchy and legitimacy forming. The light stick is an official product, and its status as a symbol of the relationship between idol and fan is recognized.

This is why the fans purchase light sticks without a fight, and light sticks are now an official merchandise line and source of profit. Through the fluid nature of the light sticks, entertainment agencies have successfully transferred a portion of the cost of managing a concert onto the fans, a cost that they originally would have had to pay. Staging a show using the light sticks is now a customary part of the industry.

While unilaterally expanding their revenue channels and growing their market through such methods, the K-pop industry has resisted being transparent about their profit generation or distributing their earnings.

Improvement in labor rights is not only lagging pertaining not only to the idols but to the production crews and staff, who are forced to endure inhumane labor conditions because that’s simply the way the industry is.

It goes without saying that the same lack of progress is relevant to fandom rights. The cost of producing an idol group is astronomical, and it carries considerable risk. Therefore, the profits should go to the entertainment agency that made the initial investment. This is how the industry justifies it, but customs and culture within the industry exhibit a high level of unfairness when compared to the sheer scale of the industry.

When considering the intimate correlation between industry fairness and sustainability, we need to take a good look at what the future K-pop industry needs.

By Jang Ji-hyeon, idol researcher and co-author of “Femidology”

Many Koreans grew up with K-pop. While they were gravitating first toward one favorite group and then another, K-pop was expanding into a dominant genre in the global music industry and a cultural juggernaut often mentioned in the context of Korea’s national interest.

But it’s uncertain whether it will be possible to keep viewing K-pop through such rose-tinted glasses. Music labels are obsessed with profit, and fans are sick of being milked for labor under the guise of showing their support. The genre has also had its share of incidents and scandals.

In our feature series “K-pop: To Love or Let Go,” we will tackle questions that are as uncomfortable as they are essential and discuss ways to make K-pop more sustainable.

This series is brought to you by the Hankyoreh in collaboration with Women With K-pop and Field Fire.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Back to the bad old pre‑WWII days [Column] Back to the bad old pre‑WWII days](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2026/0203/2317701066525269.jpg) [Column] Back to the bad old pre‑WWII days

[Column] Back to the bad old pre‑WWII days![[Guest essay] Will humans be crushed by the AI tide, or carried by it? [Guest essay] Will humans be crushed by the AI tide, or carried by it?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2026/0203/7217701098163121.jpg) [Guest essay] Will humans be crushed by the AI tide, or carried by it?

[Guest essay] Will humans be crushed by the AI tide, or carried by it?- [Guest essay] UNC is not the boss here — Korea needs to say so

- [Column] Bond warfare threatens mutually assured destruction

- [Column] How North Korea’s upcoming party congress could change history

- [Column] American democracy is dying, and masked agents are killing it

- [Editorial] As Seoul takes on greater defense duties, UNC must adapt as well

- [Correspondent’s column] Welcome to never-ending tariff negotiation hell

- [Column] Atlas the robot and the A-bomb

- [Editorial] A slap on the wrist for Korea’s former first lady

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Dawn of the age of fascism

- 2KOSPI’s rollercoaster ride continues: Index rallies 7% to new high after 5% drop

- 3Non-homeowners suffer most from unfair surges in home prices, says Lee

- 4[Column] Telling workers that automation is unavoidable helps no one

- 5[Letters from Gaza] The war forced my mother to choose between life and limb

- 6[Column] How North Korea’s upcoming party congress could change history

- 7‘Golden’ from ‘KPop Demon Hunters’ wins K-pop its first Grammy

- 8With a click, 220,000+ member Telegram room generates illegal deepfake porn

- 9[Column] Back to the bad old pre‑WWII days

- 10[Guest essay] UNC is not the boss here — Korea needs to say so