hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

How martial law forces in Gwangju opened fire on minibus carrying 17 people

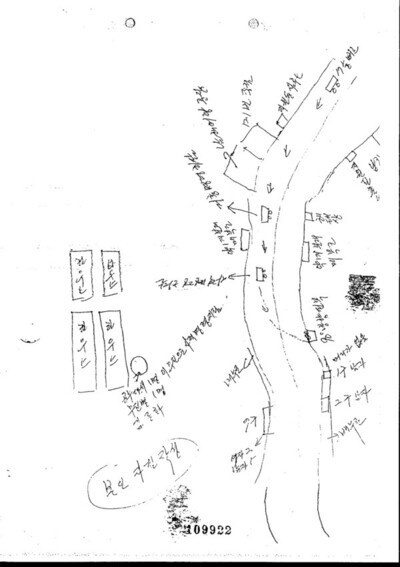

It was May 25, 1980, and a minibus carrying 17 people from Gwangju to Hwasun rounded the corner on the road next to Junam Village.

“Fire!” The military officer carrying a walkie-talkie issued the order as he looked at the minibus.

The officer gave the order to open fire in a sharp and deep voice. The sound of gunfire exploded as soldiers who had been hiding on both sides of the road began shooting at the minibus. As the tires punctured, the bus eventually came to a halt lying at a 90-degree angle on the edge of the opposite side of the road.

The soldiers continued to unleash a barrage of bullets for 2-3 minutes. After several rounds, it appeared as if they were shooting again to make sure everyone was dead.

Kim Jong-hwa, 74, who then owned a flower farm near Junam Village, witnessed the massacre in vivid detail.

Born in Masan, South Gyeongsang Province, he moved to Gwangju in December 1977 at the recommendation of a battle buddy. Right before the incident, Kim met with an officer from the airborne unit whose insignia displayed the rank of captain, as well as a radio operator, when they came to visit his greenhouse.

“Have you seen anyone suspicious passing by?” the captain asked him. “Oh, how could I have see anything?” Kim replied, to which the officer asked if he was from Gyeongsang Province. The captain appeared to be from the same region as him. Kim tried to dissuade the captain, yelling that the people were ordinary citizens on their way home and not members of the citizens’ militia, but it was no use.

The attack on the minibus came at around 8:10 to 8:20 am. “When my wife, an elementary school teacher, called me to come and eat breakfast, I asked her why she hadn’t gone to work yet, and she said that the schools had been ordered to close,” Kim said. “That’s why I remember the exact time.”

The soldiers pulled the bodies from the minibus and threw them into a sewer on the other side of the road. On May 25, Kim told the airborne unit captain, “I saw you burying the bodies, and it frightens me to death,” and asked him to identify the bodies so they could be returned to the families. After initially reacting with anger, the captain brought ten guards and assigned them to Kim, instructing him to “process [the bodies] quickly.”

The temporary burial site was a horrific scene. Around 5-10 centimeters (2-4 inches) of dirt had been scraped over the ten bodies, including those of two women, with a putrid smell and maggots everywhere. Most of the bodies had been shot anywhere from several to several dozen times.

Along with a junior of his surnamed Jung who lived nearby, Kim went to the sewer and searched through the personal belongings of the deceased, finding contact details for three of them.

One of the women was carrying an employee card for the Ilshin Spinning Company. After the army’s suppression campaign came to an end on May 27, Kim visited the company and handed over her personal information.

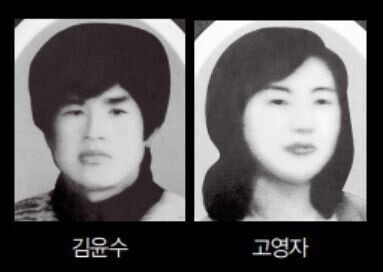

The woman, Koh Yeong-ja, 26 at the time, was a laborer at the company killed while returning to her hometown in Hwasun. Thanks to Kim, her family was at least able to receive her body.

“It’s so unfair that she was killed on her way home from the factory,” Kim said.

In 1983, Kim held a “soul wedding” for Koh and Kim Yoon-su, 27 at the time, the driver of the minibus.

The May 18 bus mass shooting at Junam Village consisted of at least five incidents, according to findings of the May 18 Democratization Movement Truth Commission, and led to at least 17 deaths based on a situation report by the Combat Training Command, but only 12 of the bodies were identified, including Koh Yeong-ja and Kim Yoon-su.

Kim, who also ran a flower shop in Gwangju, was enraged after seeing the brutal massacre at the hands of the martial law army. The body of a young man – Kim Yong-pyo, 22 – who had been shot dead outside the Labor Office on May 21 was also recovered on a stretcher.

Perhaps indicative of his readiness to die, he had left a handwritten note in his back pocket that listed his address and personal information. “I wished for his soul to go peacefully and placed a lot of budding flowers in his coffin,” Kim said.

While Kim was driving to Damyang with the coffin and the boy’s parents, his pickup truck came under fire from the martial law army in front of the old Gwangju Prison. They held a temporary burial on the outskirts of Mudeung Mountain and later moved the body to a graveyard in Gwangju.

“Does it make any sense for soldiers to turn their guns on citizens?,” Kim asked in an interview with the Hankyoreh at a farm he owns now in Gwangju on May 10.

Kim Jong-cheol, a symbolic figure in the Bu-Ma Democratic Protests that took place in Busan and Masan in October 1979, was Kim’s younger brother.

After gaining admission to Korea University’s School of Law in 1975, he had taken time off and taken part in the Bu-Ma Democratic Protests in Masan, later suffering from the aftereffects of torture. He eventually died at the age of 42 after a battle with cancer.

Kim pulled out a book called “The Era and Habits of Kim Jong-cheol,” a not-for-sale book that contains records of his brother’s life and career. “The perpetrators of the horrendous atrocities in the Gwangju Uprising should be brought to justice,” Kim said.

By Jung Dae-ha, senior staff writer

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors

- 3Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 4After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 5BTS says it wants to continue to “speak out against anti-Asian hate”

- 6AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 7Noting shared ‘values,’ Korea hints at passport-free travel with Japan

- 8Gangnam murderer says he killed “because women have always ignored me”

- 9South Korea officially an aged society just 17 years after becoming aging society

- 10Ethnic Koreans in Japan's Utoro village wait for Seoul's help