hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

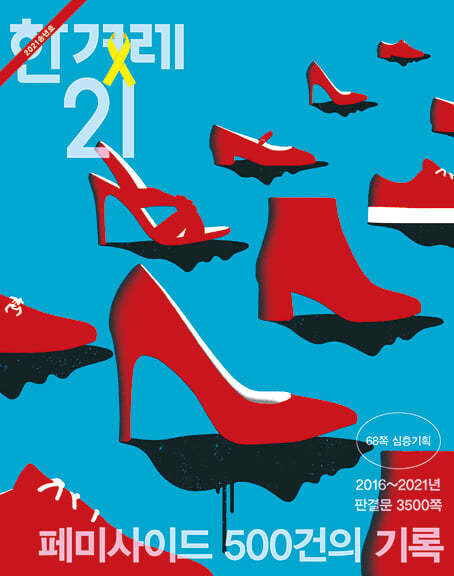

500 femicides: The epidemic of violence against women in Korea

The bodies of two young girls were discovered in the flower beds on the grounds of an apartment complex in Cheongju, North Chungcheong Province, this past May. The teenagers had courageously been speaking out about the sexual assault they had suffered.

Then in July, a woman in her 20s was gravely injured by a man she had dated in her flat in Seoul’s Mapo District. She was taken to the hospital but later died from her injuries.

In August, a criminal who had cut off his electronic ankle monitor and fled the police took the lives of two women who were working as “karaoke room assistants.”

Back in April, a woman in her 50s was killed by her husband in her apartment. Her husband had abused her for 30 years.

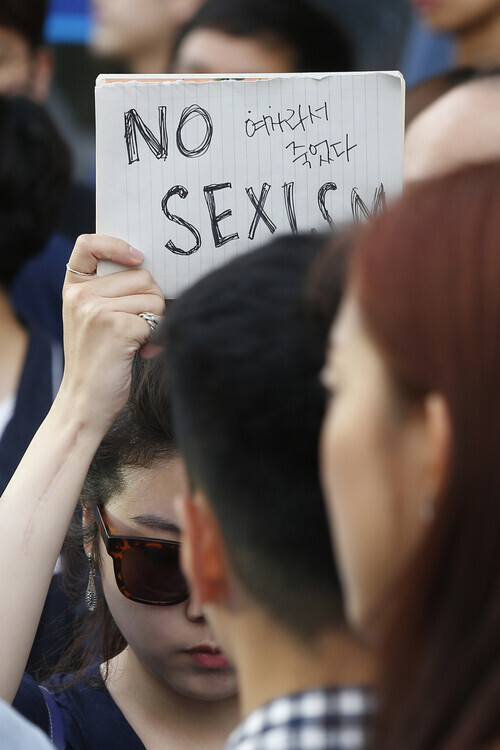

Women of all ages, in all regions, and in all classes are being killed — by men. The most extreme violence that women can suffer is called femicide, which combines “femina,” the Latin word for woman, with the suffix “-cide,” as in “homicide.”

There’s a pattern behind these deaths. The Hankyoreh 21 traced that pattern by searching press reports and court judgments. Reporters analyzed 3,500 pages of decisions in 427 criminal cases in which the first court reached a verdict between January 2016 and November 2021 and met with members of the victims’ families.

When a man kills a woman and then ends his own life, the investigators close the case, removing such incidents from crime statistics. The Hankyoreh also looked into 73 cases that ended in such a manner.

A history of abuse in 36% of these killingsNo one stopped the deaths, despite warning signs.

In 126 of 347 (36%) verdicts on the murder of a woman by an intimate partner, such as a boyfriend or husband, the killer had a history of abusing his victim. That included threatening to kill the woman (from a 2020 verdict), surveillance using a phone app for tracking someone’s location (from a 2018 verdict), and intimidating behavior such as driving into the guardrails at 140 kilometers an hour (from a 2019 verdict).

One man had been given a suspended sentence after stabbing a woman just two months before he went on to kill her (from a 2017 verdict). In short, the victims were already survivors — survivors of the daily threat of death before being killed.

Among the victims, 23 (6.6%) of 347 had even asked the police for help. But their cries for help weren’t taken seriously.

As a 2018 verdict recounts, a woman in her 30s in Seoul’s Gwanak District called the police 10 times between January and April 2018 on the man with whom she was in a common-law marriage. He stabbed her and inflicted bone-breaking injuries, and he was booked nine times on criminal charges.

But when the man was about to be put behind bars, the victim submitted a petition saying she didn’t want him prosecuted. Two months later, the man attacked her again — this time, fatally. Ten cries for help went unheard by the police, but her single request not to prosecute the man was listened to in earnest.

When such crimes take place at home, distress signals go disregarded. And in fact, the home was where 285 (67%) of the femicides occurred. Home meant the residence of the victim and killer in 177 cases, the residence of the victim in 68, and the residence of the killer in 40.

According to a 2020 Supreme Prosecutors’ Office analysis of crimes, just 47% of all homicides take place in the victim’s residence.

Explaining the importance of the settings where femicides occur, women’s studies scholar Jeong Hee-jin said, “Society is tolerant of violence that takes place in the home, a setting that can be controlled by individual men.”

“But homicides become problematic when they take place on the street, where public authorities exert an influence. That’s because it shows the impotence of male authorities,” she explained.

“Thus the question of where someone died ends up becoming a more important issue than women’s human rights.”

31% of crimes considered "brutal"Each night, individual homes are the scenes of vicious assaults. In 31% of the 107 cases of femicide referred for trial on homicide charges, the brutality of the crimes was mentioned as an aggravating factor.

Some of the perpetrators inflicted injuries through multiple attacks and the use of various implements.

In one 2018 case, a man in central Seoul’s Jung District murdered his partner by stabbing her 145 times when she attempted to break up with him.

These acts of sexist terrorism are not directed only at woman from a particular age group. Homicide can occur in all age groups and all types of relationships. Among the victims whose age was identified in their court ruling, 125 (29.3%) were in their 30s or younger, while 216 (50.6%) were in their 40s or 50s and 80 (18.7%) were aged 60 or older.

The emotional state of the male perpetrators has been a salient factor in terms of motive. The defendant’s emotional motives were cited in 300 of the cases (70%), including “resentment,” “feeling disregarded,” and “jealousy.”

In one homicide trial in 2016, the defendant said he had been “treated with disrespect for messing around and not earning money.” In another in 2017, the defendant said he was “angry after hearing [the victim] disparage his sexual prowess.”

Even women who were not close with the perpetrator have ended up slain for “provoking” a man’s emotions. They include one woman who was killed after mocking an older workplace colleague’s advice (2016 verdict), and another who was killed during a fight with a male tenant over financial matters (2021 verdict). In one 2015 case, the perpetrator killed a woman younger than him for speaking “disrespectfully” when giving him directions.

Among the murders committed in the context of a close relationship, 215 (62%) had motives directly tied to some general form of possessiveness on the perpetrator’s part, including cases involving infidelity and partners attempting to end a relationship.

One clear trend concerned the events that precipitated the attack: 98 of the victims (29%) were attacked either when either told the perpetrator they wanted to end the relationship or, in cases of divorce or separation, when they refused to reunite.

Indeed, an examination of rulings in 142 cases involving homicide against a romantic partner showed the durations of the relationships between perpetrator and victim to have been surprisingly short in some cases.

Six of the male perpetrators (4.2%) killed the victim within one month of the relationship officially beginning. Thirty-seven of the homicides (26%) happened within six months. Ninety-six of the 142 cases (70%) involved women killed within two months of the relationship beginning.

This suggests a situation where the female victims became aware of the perpetrator’s controlling tendencies early on in the relationship and attempted to either end or improve the relationship.

Do perpetrators end up paying justly for their crimes? In 57 cases involving isolated homicides with no aggravating or extenuating factors, the average sentence awarded in the first trial was 14.4 years. An examination of sentencing for all homicides according to the same standards in a 2019 annual report published by the Supreme Court’s Sentencing Commission showed a similar average of 14.8 years.

But in cases of isolated homicides involving the killing of a female spouse with aggravating and extenuating factors taken into account, the average was 12.8 years — markedly shorter than the 14.4-year average sentence for all isolated homicides.

In cases involving the murder of a female spouse, factors such as the surviving family members opposing punishment appear to have played a large part. In just 39 out of the 427 total homicide cases (9%), opposition to punishment was reflected as an extenuating factor. But in cases involving the murder of a female spouse, the rate was 36 out of 205 cases (17%).

By Um Ji-won, Hankyoreh 21 staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3Up-and-coming Indonesian group StarBe spills what it learned during K-pop training in Seoul

- 4[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 5Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 6[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 7[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 8Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 9Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 10Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government