hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Interview] Understanding the power of the common masses

“We very much admire the decades-old traditions of street protest and other forms of resistance in Korea. [. . . ] We conceive of the multitude as a political project that must be organized. [. . .] We totally agree that the multitude must be organized to contest exactly the hatred and exclusion that you indicate.”

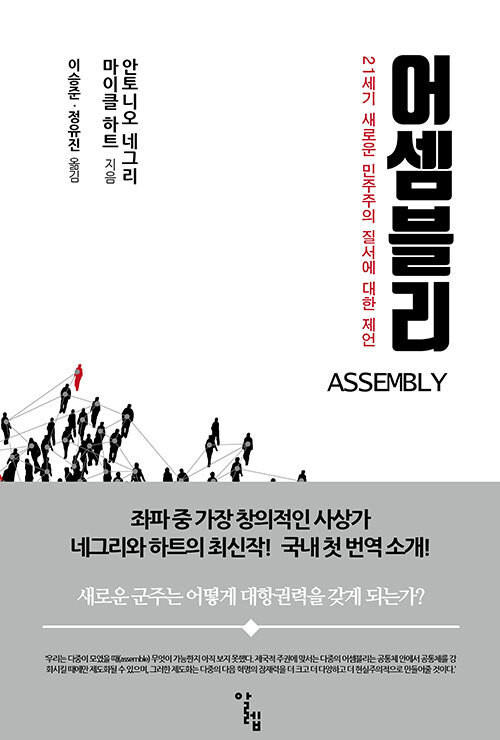

This was the response provided in an email interview with the Hankyoreh by Antonio Negri, 87, and Michael Hardt, 60, two thinkers who have offered the most intense inspiration to planning leftist political movements in the world today. The interview, which was conducted on Apr. 13 by way of their New York agency, was organized to commemorate the release of a Korean translation of their 2017 work “Assembly” (Aleph Books). In the book, the authors explore the subjectivity and practice of new polities in an attempt to investigate their potential for democratic politics in the 21st century. Negri currently travels between Paris and Venice writing and speaking before the public, while Hardt works as a professor of literature at Duke University.

Ironically, the publication of “Assembly” in South Korea comes at a time when various meetings and gatherings have been banned amid the novel coronavirus pandemic. One might expect it to be equally unsettling for the authors, who have focused their attention on assemblies and politics involving agents of political resistance -- but like the masterful analysts of global capitalist dominance that they are, they had different ideas.

“The crisis highlights, in fact, although it was already obvious before, how much capitalist production and capitalist society depends on the common [including gendered social services],” they said.

“Digital forms of assembly and of social cooperation will be essential in the era of the crisis,” they also noted.

“Keep in mind that [. . .] the common and the various modes of assembly that we relate to it are key to liberation in the future. In a post-crisis world the common and its modes of assembly will have to return, perhaps in more powerful forms,” they predicted.

South Korean readers refer to the two authors’ previous works “Empire” (2000/Korean translation 2001), “Multitude” (2004/2008), and “Commonwealth” (2009/2014) as the “Empire Trilogy.” This has to do with their interconnection in terms of the idea that the polity of the “multitude” as “new political actors” will represent a new form of practice in opposition to global capital and the order of social rule.

In their previous works, Hardt and Negri told the Hankyoreh in their response, they “attempted to understand the contemporary forms of domination exerted by global capital” and that their “projects of liberation [… involve] struggling over the meaning of concepts that […] have now been corrupted, such as democracy, freedom, and autonomy.” As part of this project, they mentioned their struggle over the vocabulary and terms used by the political left and right.

“One primary objective of our work involves struggling over concepts and developing the political vocabulary of the left,” the two writers said. “Our view is that we should not abandon the concept of democracy but instead we must struggle over its meaning because the struggle for democracy is such a central part of our tradition and expressed the hopes of so many who struggled and died before us.”

Hardt and Negri explained how “the reactionaries had taken and transformed our concepts; here we want to take one of theirs.” That concept is entrepreneurship, which they define as “a collective project to organize social cooperation.” They went on to offer the examples of “an empty building occupied by young people to create a social center” or “the practices of ‘feminist strike’ that many Latin American feminist movements have been [using to protest] against femicide and sexual violence.”

“We thought at one point of titling our book ‘Enterprise’ instead of ‘Assembly’ and having the emblem of the Starship Enterprise [from the Star Trek media franchise] on the cover — but we decided [that] kind of humor and irony [. . .] might not be grasped by some readers,” the two authors added.

When the Hankyoreh reporter observed that South Korea’s street protests have come to include radical rightists and moderate conservatives and that this “multitude” encompasses complex forms of hatred and exclusion grounded in gender, place of birth, residence, and class, Hardt and Negri offered the following rejoinder: “Not all social movements are progressive or aimed at liberation. [. . .] We should emphasize [. . .] that our notion of ‘the multitude’ does not simply designate the masses or the population as a whole in an indifferent way.”

“Feminist and proletarian political projects must find ways to cooperate in a shared struggle. [. . .] Capitalist domination and patriarchy are intimately intertwined,” the authors also said.

“Our concept of the multitude is close to — and we have learned a great deal from — the theory of intersectionality developed by black feminists in the United States.”

By Lee Yu-jin, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 4Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 5Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 6No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 7[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 8Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 9N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 10Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report