hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Why Russia overwhelmingly voted to give Putin a 30-year dictatorial rule

The Hankyoreh’s senior staff writer Jung E-gil breaks down common questions, offering easy-to-understand interpretations of global news.

Getting up to speed

In the Russian presidential election that ended on Sunday, incumbent Vladimir Putin, 72, secured a fifth term by an overwhelming margin. After his victory, he declared that Russia “needs to be stronger and more efficient.” [. . .] The Russian news agency TASS cited an announcement from the Russian Central Election Commission stating that Putin had earned 87.21% of the vote with 90% of ballots counted. This was the highest rate ever in Russian presidential election history. But in the rest of the international committee, the election has been strongly criticized as “unfair,” with no registered candidates opposing the war in Ukraine. (Hankyoreh, March 18)

Q: Thirty years in power? That’s a long time.

A: Putin rose to Russia’s most powerful position for the first time on Dec. 31, 1999. It marked the eve of the end of one millennium and the beginning of the next.

Without question, Putin has changed Russia. Some indication of how adept he is at wielding power can be seen in the way he settled in the position of prime minister to avoid a constitutional provision barring presidents from serving a third consecutive term, before eventually returning.

While serving as prime minister from 2008 to 2012, he had Dmitry Medvedev serve as something of a proxy president, appointing himself the role of “retired emperor” until his return to the presidency in 2012. Even the ironfisted Soviet leader Joseph Stalin was unable to achieve a similar feat.

Putin also enabled his own reelection through a July 2020 amendment to Russia’s constitution extending the president’s term from four years to six. This paved the way for him to remain in power until 2036.

By that time, he would be 84 years old — although this does not seem all that strange if we consider that 81-year-old Joe Biden is vying for reelection in the US right now.

Q: Didn’t Putin himself claim that former Russian President Boris Yeltsin wanted to transfer power to him at first, and that he turned it down at the time? How has he managed to stay in power for so long?

A: As many people are aware, Putin worked during the Soviet era as an agent for the KGB, a secret intelligence organization. He is also said to have worked as a taxi driver for a time amid the economic woes that followed the Soviet Union’s collapse.

After assisting with an election campaign for the Saint Petersburg mayoral race, he moved in 1996 to Moscow, where he was successfully promoted to deputy chief of the Presidential Property Management Directorate and deputy head of the Executive Office of the President. His duties involved the relocation of previous Soviet assets to Russia.

It was a time when corruption and collection was rife between bureaucrats and the oligarchs, business entrepreneurs who had amassed wealth by acquiring formerly state-owned assets after the Soviet Union’s dissolution. Putin appears to have fully grasped the core contradiction in Russia at the time: the workings of plutocracy.

From there, he went from strength to strength. In May 1998, he became the director of the Federal Security Service, the successor of the KGB. On Aug. 9 of the following year, he was appointed first deputy prime minister and acting prime minister. Then-President Boris Yeltsin even made the shocking announcement that Putin would be his successor.

On the same day, Putin announced that he had agreed to run for the presidency. Power had suddenly fallen into his hands.

At the time, Yeltsin’s popularity was at rock bottom, owing to the social disorder and economic devastation that had persisted over his 10 years in power. He was also suffering from the physical and psychological ravages of alcohol abuse. Allegations of corruption involving himself and his family had started to emerge.

Yeltsin needed to avoid going to prison, and he saw Putin as the only person who could guarantee him a future after he stepped down.

Putin’s first day as acting president came on Dec. 31, 1999. That day, he paid a visit to Chechnya, which had declared its independence and was opposing Russia. While there, Putin vowed not to retreat. This was his declaration of the return of Russia as a major power.

After that, he signed his first presidential order, which handed out pardons for the corruption charges facing Yeltsin’s family. On May 26, 2000, he became the official president, earning 53% of the vote in the election.

Q: Why do Russians like Putin so much?

A: It’s a combination of his own capabilities and Russia’s situation. To some extent, he was able to resolve the issues of government-business collusion between the oligarchs and bureaucrats that had persisted in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse.

Of course, this also meant the elimination of potential political rivals. In their place, he left a group of oligarchs who were more favorable for him.

He also revamped laws on land, taxation, and labor to establish a state management system. As petroleum and other raw material prices climbed, the Russian economy made a comeback. When he came to power in 2000, petroleum cost around US$20 a barrel; by the time he finished his second term in 2008, that was up to US$140.

Besides petroleum, natural gas and other abundant raw materials further enriched Russia’s coffers.

If you look at World Bank statistics, Russia’s GDP in 2000 was US$1 trillion dollars in terms of purchasing power parity. Eight years later, it was 3 trillion. Right before the war in Ukraine, it had jumped up to 5.327 trillion.

Law and order have been restored, the economy is improving, and he gave Russians the hope of seeing Russia reemerge as a global superpower. Isn’t it obvious that his public approval is going to go up?

Q: OK, I get that Putin improved the economy. But he’s a brutal dictator. People say he has mountains of assets stored offshore. How could such an unsavory character stay in power for so long?

A: I’ll offer some historical context. Some say that Putin, the 21st-century czar, is a product of an expansionist police state that arose from the traditional security anxiety inherent to the Russian people. George Frost Kennan, the American diplomat who aptly predicted the Soviet Union’s collapse decades before it happened, wrote in his “Long Telegram” to the Truman administration that the Kremlin's “neurotic view of world affairs” is based on a “traditional and instinctive Russian sense of insecurity.”

Following the creation of the principality of Moscow, Russia has consistently pursued an expansionist policy. Born from the vast Eurasian plains, protected by no natural barriers, Russia was under constant threat from its hostile nomadic neighbors. You could say it began expanding its territory from a perspective of self-preservation. Yet by expanding its territory to encompass the various tribes of surrounding territories, it now faced the challenge of governing all these foreign peoples. These foundational conditions gave the Russian people a taste for militaristic nationalism and autocratic strongmen who could allay their anxiety about domestic stability and national security.

Following World War II, the Soviet Union acquired vast amounts of territory, from East Germany in the west to the island of Sakhalin in the east. The Russian empire, so to speak, had reached its largest size in history. The Soviets employed Eastern Europe as a shield against the West, and yet in doing so, they once again inherited the challenges of governing various peoples and nationalities.

Having preemptively sensed the Soviets’ internal contradictions and insecurity, Kennan called for their containment. He accurately predicted that continuous containment would allow the Russians’ inherent contradictions and insecurities to boil over into the Soviets’ collapse. While Kennan accurately predicted the Soviet collapse, Russia’s geopolitical cycle of insecurity-expansion-collapse is not over. It’s just entering a new era.

The decade of chaos and instability following the Soviet collapse gave rise to another autocratic leader: Putin. Once again, the Russian people sought a strongman who could resurrect the secret police and state security apparatuses reminiscent of those that reigned under imperialist czars and Stalin. Of course, that was none other than Putin.

Q: You said that when Putin became acting president, he immediately turned his attention toward Chechnya. Didn’t Putin ruthlessly suppress political resistance in that region?

A: The Chechen separatist movement was symbolic of waning Russian influence following the Soviet collapse. Chechnya is also home to the Caucasus Mountains, which had effectively served as a natural southern barrier. If Chechnya had been allowed to separate, that would have caused a separatist chain reaction among the Muslim peoples within Russia. That chain reaction would have gone off like a bomb.

Yeltsin was a bit of a pushover; Putin was not. He immediately mobilized the military to quell the separatist movement. Movsar Barayev, a Chechen Islamist leader, seized the Dubrovka Theater in Moscow in 2002, taking over 800 hostages and demanding Russia’s withdrawal from Chechnya. To resolve the crisis, Putin dispatched a Spetsnaz unit, who filled the theater with gas to kill the hostiles. The Russian special forces succeeded in suppressing the Chechen militants, but at the expense of at least 150 hostages.

It was a defining moment for Putin. Russia was once again at the cusp of an expansionist era. Seduced by nostalgia for a great Russian empire, the Russian people opened their arms to Putin.

Q: But doesn’t economic development usually lead to a development toward democracy? Putin’s supposed popularity seems based on his suppression of any political opposition. Navalny died in prison right before the election. Doesn’t this suggest that, deep down, Putin fears political opposition?

A: There are certainly opposition forces within Russia. It is also true that Putin works tirelessly to suppress them. But it’s also true that these opposition forces aren’t enough to threaten Putin’s rule. The Russia of today is not the Russia of Stalin’s days, where even a whisper against the government was silenced. Protests against the war in Ukraine recently broke out in both Moscow and St. Petersburg. Some newscasters even openly criticize the war on camera.

However, the majority of Russians support Putin. Regardless of how you may feel about Putin, anybody who wants to understand Russia needs to look that fact straight in the face.

Q: Western nations hit Russia with heavy sanctions after the war broke out. Yet you’re telling us that Russia’s economy is doing fine?

A: According to Russia’s Federal State Statistics Service, Russia’s GDP in 2023 increased by 3.6% compared to the previous year. The IMF also says that Russia’s economy grew by 3% in 2023, and projects a growth rate of 2.6% for this year. This growth rate exceeds that of the US and any other G7 nation.

The US hit Russia with unprecedented sanctions following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The sanctions froze US$300 billion in overseas assets, cut Russians off from the SWIFT financial message network, reduced Russian oil and gas exports, and pulled Western companies out of Russia. At the onset of the war, the Russian ruble tanked, and the country suffered various shortages of essential supplies. The economic growth rate for 2022 was minus 1.2%.

However, Russia quickly recovered its industrial capacity. They sold gas and oil to India and China at reduced rates. India and China did not partake in the sanctions, and have since fortified their economic relationship with Russia. Even Saudi Arabia, technically a US ally, did not partake in the sanctions, raised their own oil prices, which worked in Russia’s favor.

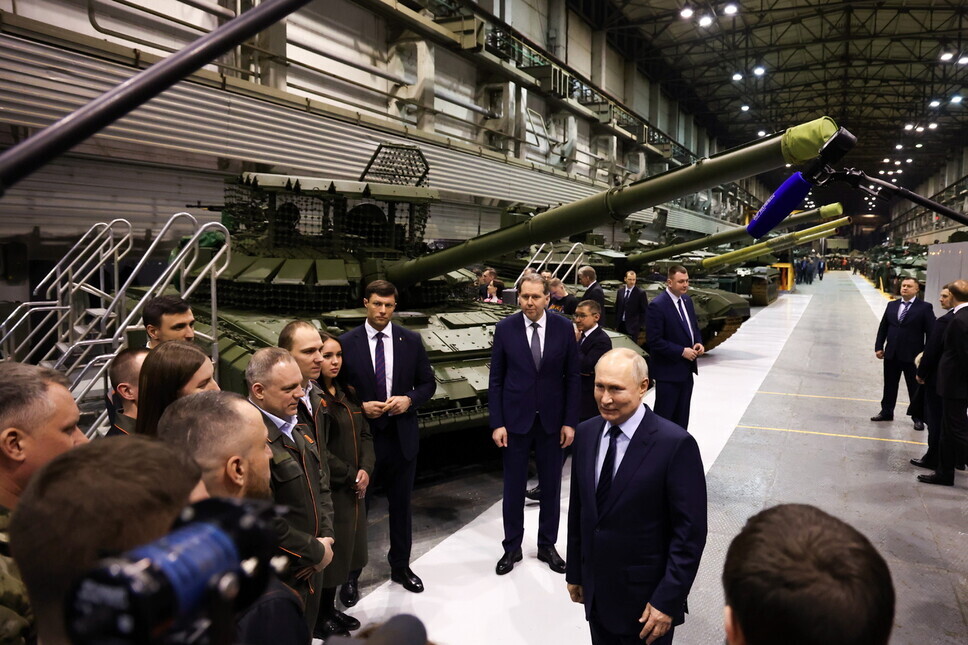

In a way, the potential productivity of Russia’s heavy industry has recovered. Russia’s heavy industry grew out of the global arms race during the Soviet era. In a sense, war has actually tapped into Russian industry’s productivity.

Q: That makes sense when you’re talking about the munitions industry, but doesn’t isolation from the West lead to a lull in technological innovation when it comes to cutting-edge industries? Wouldn’t that lead to an overall economic regression?

A: Simply put, that is the case. When Russia and China seemed to have resigned themselves to separating from the West at this point, and are attempting to form their own economic bloc. In a sense, they’re diversifying. Trade between Russia and China in 2023 amounted to US$240.1 billion. That’s an increase of 26% from the previous year. The two countries have increased cooperation on the energy front in oil and gas. They’re also attempting to build an international monetary network that excludes the US dollar in the form of BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa). Last year, BRICS moved to accept the membership of Saudi Arabia, Iran, Egypt, Argentina, Ethiopia and the United Arab Emirates.

Obviously, Russia and China will be hurt by being cut off from the West’s technological innovations, but we’ll have to see what happens going forward. When Russia, with its abundant resources and technology, joins forces with the production powerhouse and massive population/market of China, then you sprinkle India, Brazil and South Africa on top to boot, you’re looking at a force to be reckoned with.

Q: So now that the election’s over, will Putin make a trip to North Korea? Will Yoon send Putin a letter congratulating him on his reelection?

A: Putin will likely set down in North Korea this coming April or May. As far as North Korea sees it, the current situation is as good as things have gotten since the fall of the socialist bloc in the early 1990s. Following the breakdown of its summit with the US in Hanoi in 2019, North Korea threw in the towel on negotiations with Washington and Seoul and decided to ramp up its nuclear might instead. In this multipolar world order with China and Russia, Pyongyang sees new room for maneuvering.

In an interview broadcast locally on March 13, Putin said that North Korea “has its own nuclear umbrella,” all but explicitly saying that Russia will recognize the North as a nuclear weapon state. If Pyongyang beefs up its ties with Moscow, it will feel less of a need to rely on dialogue or negotiations with Washington or Seoul.

Every since he was running for president, President Yoon Suk-yeol has bad-mouthed China and Russia. Then, once he took office, he went all-in on trilateral, and triangular, cooperation with the US and Japan. Last year in April, he mentioned the possibility of Seoul providing military aid to Ukraine, nearly doing in South Korea’s relations with Russia all together.

So, you ask if he’ll send a congratulatory letter to Putin? Sure, maybe — provided that the US or Japan does so first. But do we really think that will happen?

By Jung E-gil, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 3[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 4Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 5Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 6[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 7[Special report- Part III] Curses, verbal abuse, and impossible quotas

- 8Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 9S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 10The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan