hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

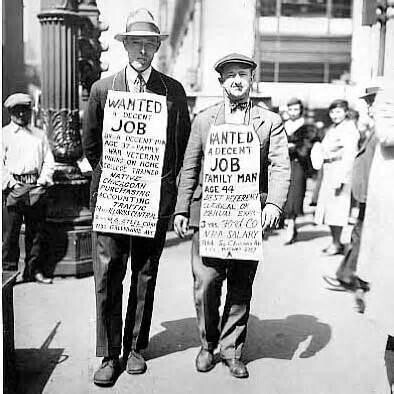

Why America is facing the worst inequality since the Depression, and what can be done

Editor’s note: The leader of South Korea’s main opposition party went on a hunger strike, a motion consenting to his arrest was passed by the National Assembly, which led to a protest by his supporters, and a warrant for his arrest was requested and then subsequently rejected. The intense political confrontation currently unfolding in Korea is not unusual, however. Even in the United States, which has long portrayed itself as a bastion of democracy, the Capitol was overtaken by rioters three years ago, and a former president is now under indictment. We are witnessing the rise of a climate where political opponents are increasingly seen as “enemies.” This crisis of democracy, intertwined with challenges like a struggle for global hegemony, wars, and inflation, is exacerbating public unease. In light of these developments, the Hankyoreh is publishing a series of articles in anticipation of the Asia Future Forum, which will be held on Wednesday, Oct. 11. The pieces in this series will delve into the root causes of these crises and explore potential solutions, in line with the forum’s theme: “The Age of the Polycrisis: A Way to Coexistence.”

This year’s John Bates Clark Medal was awarded to Gabriel Zucman, a professor of economics at UC Berkeley. The honor is presented each year by the American Economic Association to an economist under the age of 40 who has made significant contributions to the field. Zucman’s sophisticated tracking of tax evasion and measuring of income inequality were cited in the association’s reason for choosing to honor him.

On Wednesday, Oct. 11, Zucman will give a keynote presentation titled “The Price of Inequality, and Who Pays the Bigger Bill” at the Asia Future Forum, which is hosted by the Hankyoreh. Here we present our interview with the economist, which took place on Sept. 11 over Zoom.

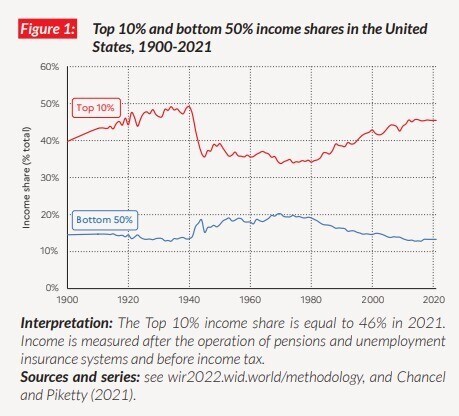

Zucman: The top 1% highest income earners in the US used to earn about 10% of total national income in the 1980s, and today they earn more than 20% of total national income, so their share of total national income has been multiplied by two. This share of 20% for the top 1% highest earners is about the same as their share in 1929 on the eve of the Great Depression. In terms of income inequality, the US is back to the very high level of inequality that existed in the 1920s — and that’s the highest level of inequality that’s been observed in the US since its creation.

If you look at wealth, the picture is pretty much the same. Wealth is more concentrated than income pretty much everywhere and always. But the dynamics have shown a very significant increase, just like income. In 1980, the top 1% used to own 20%-25% of total wealth, and today the top 1% by wealth owns about 40% of total wealth. Again, we’re back to the level of concentration that was observed a century ago, at the beginning of the 20th century.

Hankyoreh: What’s caused inequality to become so severe?Zucman: A mixture of factors, what is sometimes called the turn to market fundamentalism in the 1980s: decline in tax progressivity, fall of minimum wage, decline in public investment in infrastructure and higher education, changes in the regulation of money in politics.

Hankyoreh: What sort of negative effects has inequality had?Zucman: For the very rich, wealth is power. It’s the power to influence policymaking; it’s the power to influence politics more broadly. It’s the power to influence the prevailing ideology by newspapers or media. It’s the power to influence markets by buying companies, new entrants, by protecting monopoly positions. So wealth is power for the rich, which means that an extreme concentration of wealth leads to an extreme concentration of economic and political power. So there’s a tension between democratic ideals on the one hand and the concentration of wealth on the other hand.

Zucman: We see that inequality varies a lot across time and space, suggesting a key role for policies. Many people have become convinced that there’s not a lot that the government can do to regulate the economy, to regulate inequality. That’s what’s been told to the population for many decades: That in a globalized world, what the government can achieve is very limited because if you try to tax corporations they will go abroad, if you try to encourage unions and high working-class wages, then production is going to be outsourced. There are many different forms of globalization that are possible. It falls on us, as interconnected nations, to decide what form of globalization we want.

It’s not the case that inequality has increased at the same pace everywhere. There are, in fact, very important differences. In the US, the top 1% income share has increased from 10% in 1980 to 20% today. If you look at continental Europe, it has increased from about 10% in 1980 — the same starting point as the US — to about 12% today. This suggests that what really matters is the different policy options that have been chosen by countries. If it was only technological change, or international trade, or globalization, we should have seen inequality increase very fast in Europe, for instance. But I’m more convinced by the argument that domestic policy, like taxation, market regulation, minimum wages have had a bigger role.

Hankyoreh: What happened in the US in the ’80s?Zucman: When Reagan enters the White House in 1981, the top marginal income tax rate is 70%. At the time, it’s the highest tax rate for high earners among all industrialized countries. And then in 1986 — just five years after — this rate is reduced to 28%. That’s the lowest rate of all industrialized countries at the time. It’s clear that by and large that that has not been a success; it’s been a pretty large failure. The reality is that the growth performance of the US has been quite poor since the 1980s. Not only has growth declined, but growth and income have become much more unequally distributed. You have a situation where about half the population has been excluded from economic growth since the 1980s.

The US has gone very far in one direction of saying: Look, we are going to allow people to become very, very rich if they want to; we’re not going to collect taxes, and it’s going to trickle down and eventually benefit the rest of the population. But that has not been enough. The core engine of economic growth is not low taxes for the rich, it is access to high-quality education for all, access to good health care for all, and good public infrastructure.

Hankyoreh: Do we need to bolster progressive taxes and implement a wealth tax?Zucman: Taxation is probably the most powerful tool for regulating inequality. If we want to break the cycle of extreme wealth concentrating into extreme political power, we have to start by taxing the super-rich. And the way that this is going to work is with a progressive wealth tax on wealth itself. We need to introduce taxes that are really going to be binding and biting for wealthy people.

By Ryu Yi-geun, senior staff writer; Ro Young-joon, research assistant at the Hankyoreh Economy and Society Research Institute

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 21 in 5 unwed Korean women want child-free life, study shows

- 3Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 4Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 5[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 6[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 7Marriages nosedived 40% over last 10 years in Korea, a factor in low birth rate

- 8[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 9‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 10Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?