hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] Bleak premonitions of a redo of the First Sino-Japanese War

By Gil Yun-hyung, editorial writer

The long-awaited confrontation between the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Combined Fleet, led by Marshal-Admiral Sukeyuki Ito (1843-1914), and the Chinese Beiyang Fleet took place a mere two days after the Battle of Pyongyang, on Sept. 17, 1894.

The Combined Fleet, which departed its anchorage of Jangsan Cape in Hwanghae Province on Sept. 16, at 5 pm, proceeded toward Haiyang Island, located to the northwest. At 10:23 am, the fleet spotted black smoke billowing from an enemy vessel on the northeastern horizon.

Cognizant of each other’s presence, the two fleets entered a battle in the Yalu River estuary that would go down in the history of modern naval warfare. The fleet to emerge triumphant from this conflict would secure control of the Yellow Sea and ultimately the Korean Peninsula.

At approximately 12:50 pm, the flagship of the Beiyang Fleet, the Dingyuan, with a displacement tonnage of 7,337, charged toward the enemy, firing its first salvo from its 30.5 cm main guns at the Yoshino, a Combined Fleet vessel with a displacement tonnage of 4,216, that was located around 5,800 meters away. So started the Battle of the Yellow Sea.

Before any shots were fired, many projected that the Beiyang Fleet, which possessed the Dingyuan and the Zhenyuan, considered the best warships in Asia, would win. But reality proved those theories false.

Ding Ruchang (1836-1895), a Chinese commander who took his own life the next year, chose to utilize a line abreast formation, where ships are arranged side by side and charge the enemy simultaneously, while the Combined Fleet adopted a line ahead formation, where vessels are put in single file. The deciding factor that solidified who won and lost was the speed of the ships.

Japan was set to win the battle when the vanguard squadron of four ships led by Kozo Tsuboi successfully passed the Beiyang Fleet’s front at high speed and executed a sharp right turn. As a result, the cruisers at the far right of the formation — the Yangwei and Chaoyong — were scuttled after a mere 30 minutes, due to concentrated enemy fire. Having lost its combat capability, the Beiyang Fleet withdrew to its naval base in Weihaiwei, Shandong Province.

How do the Chinese remember this combat? After visiting the site that was previously the naval base for the Beiyang Fleet on June 12, 2018, Chinese President Xi Jinping commented, “The doors to our hefty, heavy history have swung wide open to educate me of the warnings we can take from war and various other lessons.” What does that comment mean?

According to “The Politics of Xi Jinping,” written by Takashi Suzuki, a professor at Daito Bunka University, Xi gathered high-ranking officers at the rank of senior colonel and above in May 2017 to say, “I have repeatedly referred to the First Sino-Japanese War as an example. The collapse of the Beiyang Fleet wrecked the gate protecting our seas, allowing alien invaders to come and go as they pleased, ultimately conquering and occupying our lands. The Treaty of Shimonoseki approved Japan’s rule over Korea and ceded the Liaodong Peninsula, Taiwan and the Penghu Islands to Japan. It was from this point in time that the seeds of trouble over Taiwan were sown. These historical events left deep, lasting wounds in our hearts.”

What international order will China, which still cradles this historical trauma, pursue? Xi, who became the leader of China in March 2013, has adhered to a singular national goal: “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” This great rejuvenation probably involves bringing back the international order of East Asia to the state it was in before the Sino-Japanese War.

If that is to happen, China will need to complete its goal of unification by absorbing Taiwan, and reincorporate the entire Korean Peninsula, which was its former vassal state, back into its sphere of influence.

That explains why Xi made the extreme claim that “Korea used to be a part of China,” according to Donald Trump, during his first face-to-face meeting with the US president in April 2017, leading Trump, who likely possessed little insight into East Asian history, to comment, “After listening [to Xi] for 10 minutes I realized that [East Asian history] is not so easy,” during an interview with The Wall Street Journal on April 12, 2017.

We cannot dismiss Xi’s call on Jan. 5 for South Korea to stand “on the right side of history” as something trivial. If the US and China, now dubbed the G2, implement a grand bargain that divides the Pacific, the Chinese people’s passion to overcome historical trauma will clash with the identity of Koreans, who have carved out their lives as citizens of a democratic nation. If Korea resists, we will have to endure humiliation worse than what Japan is experiencing.

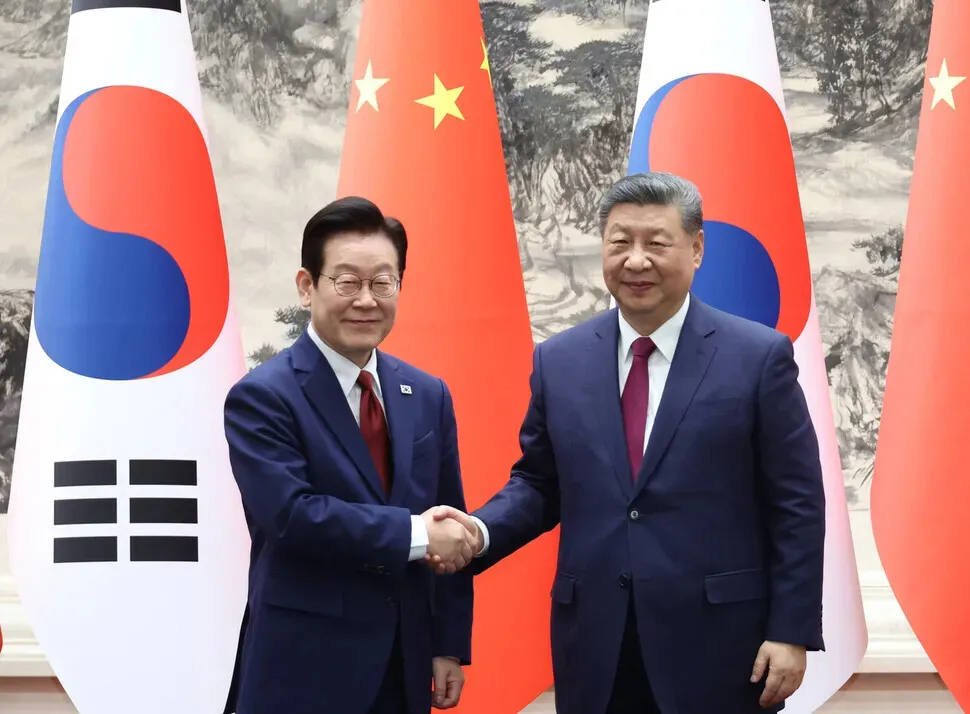

President Lee Jae Myung’s visits to China and Japan achieved a lot, but it seems clear that all of East Asia is entering an era of uncertainty that harkens back to the late 19th century. As for now, all I can say is that I have a bleak premonition of what may come.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] 23-year sentence for Han is a fitting condemnation of self-coup [Editorial] 23-year sentence for Han is a fitting condemnation of self-coup](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2026/0122/5117690709860757.jpg) [Editorial] 23-year sentence for Han is a fitting condemnation of self-coup

[Editorial] 23-year sentence for Han is a fitting condemnation of self-coup![[Column] Bleak premonitions of a redo of the First Sino-Japanese War [Column] Bleak premonitions of a redo of the First Sino-Japanese War](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2026/0122/3117690705949079.jpg) [Column] Bleak premonitions of a redo of the First Sino-Japanese War

[Column] Bleak premonitions of a redo of the First Sino-Japanese War- [Editorial] All ties between Shincheonji and PPP must be revealed

- [Editorial] Why did former staffers in Yoon’s presidential office fly drones into North Korea?

- [Editorial] Trump must stop destabilizing world with threats of conquest

- [Column] After 16 years, Korea’s ‘K-shaped’ economy is back

- [Column] Trump overturns the world order

- [Editorial] One tariff after another

- [Editorial] Obstruction conviction is first step toward bringing Yoon to justice

- [Column] ‘Be Good’ and America’s democracy

Most viewed articles

- 1[Interview] Judith Butler: Repressive acts by anti-democratic regimes are ‘confessions’ of fear

- 2‘Being alive is uncomfortable’: North Korean POWs in Ukraine speak a year after capture

- 3Korean court rules 2024 martial law crisis an ‘insurrection,’ sentences ex-PM to 23 years

- 4[Column] Bleak premonitions of a redo of the First Sino-Japanese War

- 5How conviction of Korea’s former PM could impact verdict in Yoon’s insurrection trial

- 6‘Not comparable to past insurrections’: Why court threw the book at Korea’s former PM

- 7[Editorial] 23-year sentence for Han is a fitting condemnation of self-coup

- 8Religious interference in politics a ‘road to ruin for a country,’ says Lee

- 9‘Poverty amid plenty’: Why Korea’s exchange rate is rising despite abundance of dollars, according to BOK

- 10Investigators secure testimony that Lee Man-hee ordered Shincheonji followers to join PPP