hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

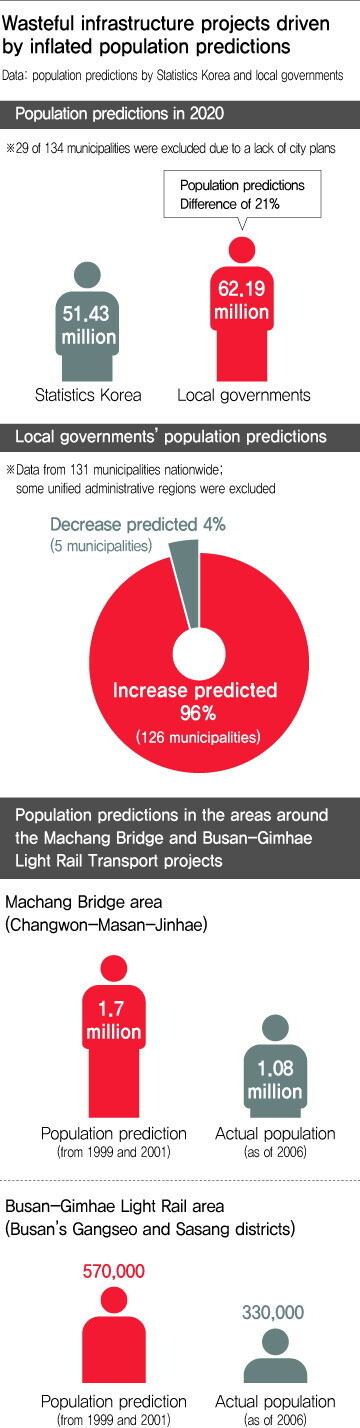

[Special report] Inflated population stats lead to wasteful public infrastructure

By Ryu Yi-geun, staff reporter

“The magical bridge that will tie the Masan, Changwon, and Jinhae areas together into a single community.”

At one time, South Gyeongsang Province was proud of Machang Bridge, but today the bridge is an example of troublesome privately funded public works projects. Last year alone, the province had to hand over 11.3 billion won (US$10.63 million) in taxpayer money to the operator, as required by the minimum revenue guarantee system.

This absurd situation results from the fact that only 45% as many cars actually use the bridge than was predicted.

Minimum revenue guarantee is a system according to which the government must provide the difference between the predicted usage and actual usage of a public infrastructure to the private operator.

In reality, the unrealistic estimate of traffic on the bridge reflects a complete failure of demographic predictions.

When Seoul National University (1999) and Keungil (2001) were predicting the number of vehicles that would use Machang Bridge, they assumed that the population of the Masan, Changwon, and Jinhae area would total 1.7 million in 2006. But the actual population that year was only 1.08 million. The two estimates were 57% off the mark.

The same problem occurred at Busan-Geoje Fixed Link bridge-tunnel (Geoga Bridge), which is located a few dozen kilometers south of the Machang Bridge in Jinhae Bay.

The Yooshin Engineering Corporation, which was commissioned in 1998 to estimate demand for the roadway, predicted that the population of Geoje Island and Busan in 2008 would be 16% larger than it actually turned out to be.

This is also one of the major reasons why the actual traffic on the fixed link in 2012 was 40% of the estimate, forcing local government to pay 60.3 billion won (about US$56.8 million) in taxpayer money to the operators.

“The assumption was that an increase in population would lead to an increase in vehicles, and in increase in vehicles would lead to an increase in traffic,” said Kim Hae-yeon, adjunct professor at Koje College and former councilor for South Gyeongsang Province. “Since they used a faulty population sample, it was inevitable that actual traffic would not meet the inflated expectations.”

Similar problems are affecting Busan-Gimhae Light Rail Transit. In 2012, only 18% of the estimated number of passengers actually rode the system. The city of Gimhae alone had to compensate the private operator 53 billion won from public coffers.

Once again, one of the biggest factors here was that the planners’ population projection for the Gangseo and Sasang districts of Busan - the people who would be using the rail line - turned out to be 72% too high.

There was something in common about how the number of users was calculated for these problematic projects: the estimates relied on the master plans of local governments. The reality is that the population estimates in these master plans were largely inflated, which led to construction of unneeded public infrastructure.

The most important factor to be considered when building such infrastructure - in which trillions of won are invested every year - is the future population of the area.

The question of whether or not to initiate a construction project is largely determined by estimated demand, which is an attempt to assess the financial feasibility of the infrastructure.

Population is a key factor in estimating demand, or in other words predicting how many people will make use of a road, bridge, railway, or some other facility.

An exaggerated population estimate can not only lead to an inflated estimate of demand but also inevitably leads to excessive investment in infrastructure that reflect the estimated demand.

The structural cause for infrastructure projects that have been bleeding public funds for dozens of years is to be found in inflated population estimates.

On Oct. 13, the Hankyoreh reviewed the population predictions found in master plans from 134 local governments across South Korea. The analysis found that according to these predictions, the population of South Korea around 2020 (the year varied according to region) would exceed 62.19 million people.

This is a wildly inflated figure, more than 21% higher than the 51.43 million people in the 2020 population projections by Statistics Korea, which provides the most accurate population statistics.

The gap between these projections becomes even wider if the 29 local governments that have not prepared master plans are included.

As the master plans from local governments containing these population projections have legal precedence, they are reflected when local governments estimate how many people will use local infrastructure projects that they are promoting.

Only five of 131 local governments - including Seoul, Jeju City and Seogwipo - had drawn up plans in which the 2020 population was expected to fall below the number of residents who were registered in 2012.

(There are a total of 134 local governments, but this article excludes unified administrative regions such as Changwon that are inappropriate for purposes of comparison.)

That is to say, more than 96% of local governments in South Korea forecast that the population in their region is going to increase. This is the complete opposite of what is actually happening. With the exception of Seoul and its surrounding cities, the population is falling in most cities and counties in South Korea.

One particularly egregious example is the counties of Yeongam in South Jeolla Province and Hadong in South Gyeongsang Province which assume that their populations will increase by a factor of three. This would mean, for example, that public infrastructure used by three people would be built with ten people in mind. The inevitable result of such reasoning is a surplus of public infrastructure.

It also results in huge expenditure of public funds. Projects are undertaken that were not financially feasible to begin with, and local governments find themselves obliged by minimum revenue guarantee agreements to compensate private operators for the shortfall in toll revenue resulting from the gap between the expected and actual number of users.

“Population is the basis of city planning, whether we’re talking about roads, drinking water, plumbing, or waste disposal,” said Jang Kyung-seok, an analyst at the National Assembly Research Service. “If the population indicators are not correct, the result is an excess supply of public infrastructure. This leads to the frivolous use of public monies.”

There is an obvious reason why nearly all local governments draft master plans on the assumption that their population will grow.

It is only when population increases that opportunities for development increase as well.

“Population projections form the basis for how we plan to use land and how we calculate demand for various uses of that land, whether residential, commercial, and industrial,” said Lee Jeong-seop, researcher at the Institute for Rice, Life, and Civilization at Chonbuk National University. “When population does not increase, regions are unable to set aside land for development that is needed for helping cities develop.”

Local governments generally employ the same trick to inflate their population predictions. This is the so-called “social increase” method, which assumes that various projects planned for the region will attract people to that region from surrounding areas.

This tactic breeds a vicious cycle, with unconfirmed development plans serving as the evidence for assuming future population growth, with this inflated population than becoming the excuse for additional, and unnecessary, development.

In an attempt to regulate this, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport devised guidelines for setting up master plans for cities and counties, but they have little effect.

“Approval for the plans is handled by the cities and provinces,” said an official working with the ministry’s urban policy division, on condition of anonymity. “The only thing we can do is ask them to reconsider.”

“When there is a problem with the method of calculating population or when the local governments make plans that calculate social increase using unconfirmed infrastructure projects in order to make it look like the population will increase, all we can do is inform the government in question about these issues and ask them to respond. Many local governments are violating the regulations, but there are not any penalties to speak of,” the source said.

Backing up these excessive population estimates is an obsession with development and growth.

“The leaders of local governments don’t get votes unless they say that the city is going to grow,” said Byeon Chang-heum, professor at Sejong University. “It might be painful, but we need to create a new urban paradigm. We must try to improve the welfare and satisfaction of residents in a way that is appropriate for a decreasing population.”

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Life on our Trisolaris [Column] Life on our Trisolaris](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0505/4817148682278544.jpg) [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

[Column] Life on our Trisolaris![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2New sex-ed guidelines forbid teaching about homosexuality

- 3[Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- 4OECD upgrades Korea’s growth forecast from 2.2% to 2.6%

- 5Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 6Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 7S. Korea discusses participation in defense development with AUKUS alliance

- 8Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 9[Reporter’s notebook] In Min’s world, she’s the artist — and NewJeans is her art

- 10[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press