hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Russian architect personally witnessed Empress Myeongseong’s assassination by Japanese ronin, account reveals

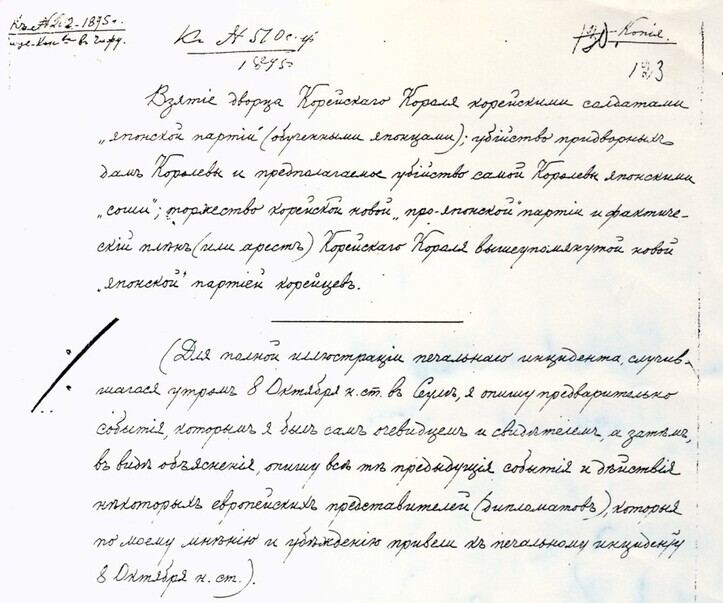

“Japanese ronin murdered women believed to be royal concubines and the empress; the Joseon king has been effectively imprisoned by an exultant new ‘pro-Japanese wing’ in Joseon.”

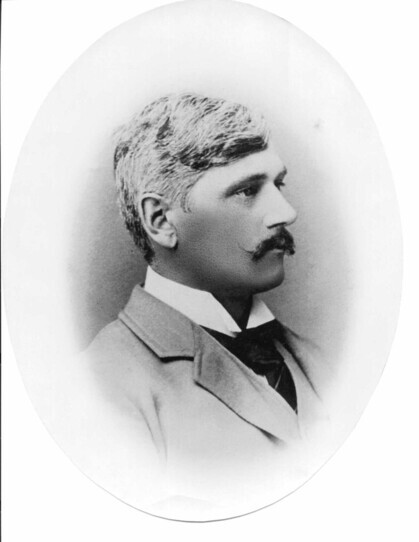

This sentence opens an eyewitness account penned 125 years ago by a Russian-born architect in his 30s, which survives today as a record of atrocities by Japan that were very nearly lost to history. The writer’s name is Afanasy Ivanovich Seredin-Sabatin (1860-1921). As a guard to the royal family, he was the only foreigner to witness and record the events early in the morning of Oct. 8, 1895, when Empress Myeongseong, wife of then Emperor Gojong, was brutally slain by Japanese ronin who had forced their way into their Gyeongbok Palace residence.

“I saw in detail the atrocity committed by Japanese thugs in the empress’s chambers. [. . .] The Japanese grabbed the Korean women by the hair and dragged them before throwing them out of the window. As I was standing in the courtyard of the empress’s chambers, the Japanese threw 10 to 12 palace women out of the window.”

“The leader of the Japanese came to me again and said, in a very stern tone, ‘We still haven't found the empress. Do you know where the empress is?’”

These passages from Seredin-Sabatin’s record, which convey the events at the time in the grisliest detail, served as conclusive evidence proving that the assassination known as the “Eulmi Incident” -- considered one of the most humiliating events in Korean history -- was orchestrated by Japan.

Arriving in Joseon in 1883 as an Incheon customs worker and civil engineer without having undergone a professional architectural education, Seredin-Sabatin made the acquaintance of the late Joseon Emperor Gojong and his wife by means of the Russian Legation. It was a truly unfortunate twist of fate. Not only was he forced to witness the events of Empress Myeongseong’s assassination, but he also spent the years from 1885 to 1890 designing and building the Russian Legation building in Seoul’s Jeong-dong neighborhood where the emperor would flee from 1896 to 1897, cowed by Japan’s intimidation. Numerous buildings that have left a major imprint on modern Korean history -- including Jungmyeong and Dondeok Halls at Deoksu Palace, Independence Gate, and Gwanmun Hall at Gyeongbok Palace -- either were designed by Seredin-Sabatin or had his involvement in their construction. Such was the tumultuous life in late 19th and early 20th century Joseon for a Russian architect born the descendant of Ukrainian nobility.

Oct. 20 marks the opening date of “The Young Russian Sabatin Comes to Joseon in 1883,” a special exhibition that commemorates the 30th anniversary of South Korea-Russia diplomatic relations by focusing on Seredin-Sabatin, a figure involved in the design and construction of numerous late Joseon buildings. Taking place on the second floor of Jungmyeong Hall, the exhibition is not large in scale, but it is significant in the way it reexamines someone who left a winding trail of footprints across Korea’s modern political and architectural history. Beginning with the prologue section that introduces Seredein-Sabatin’s records of the Eulmi Incident, the exhibition is divided into three sections titled “The Young Russian Sabatin Comes to Joseon,” “The Russian Legation Meets Sabatin’s Hand,” and “Sabatin’s Strolls through Jemulpo and Hanseong.”

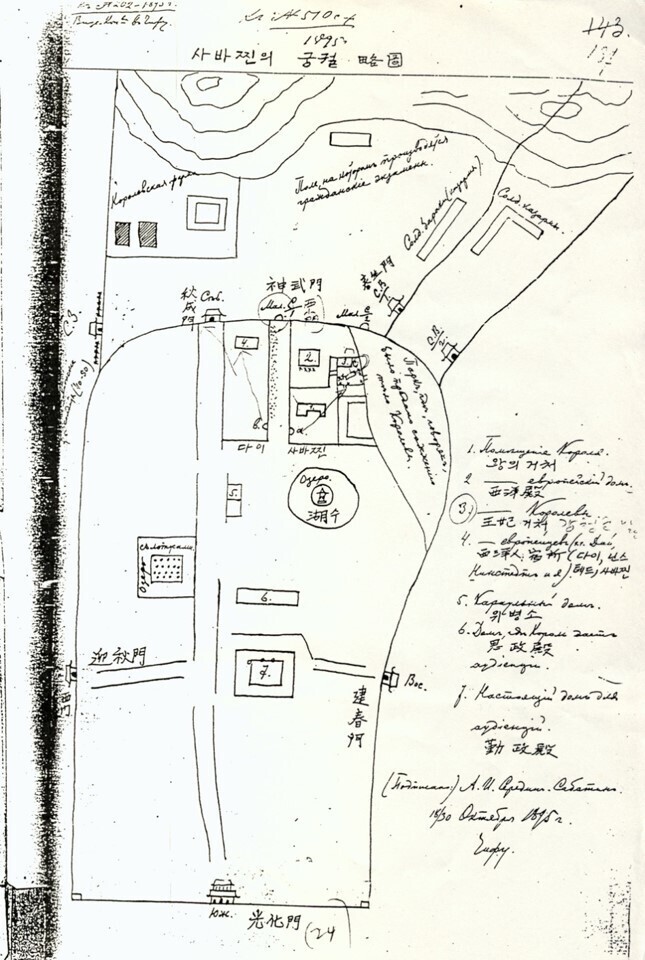

Particularly noteworthy are Seredin-Sabatin’s account and a panel photograph showing a map of the assassination site in Gyeongbok Palace that appear in the prologue section. Visitors can see the record from the Imperial Russian Archive of Foreign Policy in which Seredin-Sabatin recorded what he witnessed while on duty on Oct. 8, 1895, when Japanese military guards stationed in Hanseong (Seoul) under the leadership of Japanese diplomatic minister Goro Miura, along with consulate staff and a group of ronin, forced their way into Gyeongbok Palace and assassinated Empress Myeongseong. They can also see a photograph of a sketched map showing where the assassination took place in the palace.

Seredin-Sabatin worked at the Incheon customs house as a tide waiter before traveling to Hanseong in 1888. There, he would earn Gojong’s trust while supervising palace architecture. Feeling threatened after the assassination in 1895, he would briefly leave Joseon before returning to Incheon in 1899 and taking part in various architecture and civil engineering projects until he left again after the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904. Sections 1 and 2 of the exhibition highlight his work as an architect and civil engineer through documents and photographs related to structures he designed. For the first time, visitors can see the first and second design plans for the former Russian Legation in Jeong-dong, which is considered his masterwork; photographs from the actual construction; a handwritten construction invoice; the façade of the unfinished imperial residence; and a payment request for the Legation’s construction.

Other exhibits include photographs and models of Gwanmun Hall at Gyeongbok Palace -- which Seredin-Sabatin is believed to have been involved with -- as well as the Russian Legation and Jemulpo Club. Through these, viewers can glimpse the work of a pioneer of modern Joseon architecture. The exhibition is also effectively a report on findings from research last year by the Korea Association for Architectural History into Seredin-Sabatin’s relationship with modern Korean architecture.

“There are still many questions that need to be answered about Seredin-Sabatin’s activities, but this could be seen as an achievement in terms of allowing a detailed glimpse of his work on the ground as materials from the Russian Archive of Foreign Policy are shared with the public for the first time,” said Kim Jong-heon, a Paichai University professor involved in the research. The exhibition continues through Nov. 11.

By Noh Hyung-seok, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0507/7217150679227807.jpg) [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war![[Column] The state is back — but is it in business? [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0506/8217149564092725.jpg) [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

Most viewed articles

- 1Yoon’s broken-compass diplomacy is steering Korea into serving US, Japanese interests

- 2[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- 3Yoon’s revival of civil affairs senior secretary criticized as shield against judicial scrutiny

- 4Behind-the-times gender change regulations leave trans Koreans in the lurch

- 5South Korean ambassador attends Putin’s inauguration as US and others boycott

- 6Japan says its directives were aimed at increasing Line’s security, not pushing Naver buyout

- 7Lee Jung-jae of “Squid Game” named on A100 list of most influential Asian Pacific leaders

- 8Family that exposed military cover-up of loved one’s death reflect on Marine’s death

- 9Amid US-China clash, Korea must remember its failures in the 19th century, advises scholar

- 10S. Korean first lady likely to face questioning by prosecutors over Dior handbag scandal