hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[News analysis] Korea peace process cannot be achieved via biggest military buildup in history

“The two sides agreed to carry out disarmament in a phased manner, as military tension is alleviated and substantial progress is made in military confidence-building.”

This phrase comes from Article 3-2 of the Panmunjom Declaration by South and North Korea on Apr. 27, 2018. On that day, South Korean President Moon Jae-in and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un pledged to establish a “permanent and solid peace regime.” How have things turned out in reality? An intermediate-term national defense plan for 2021-2025 presented by the South Korean Ministry of National Defense (MND) on Aug. 10 announced plans for 301 trillion won (US$253.4 billion) in spending over the five-year period.

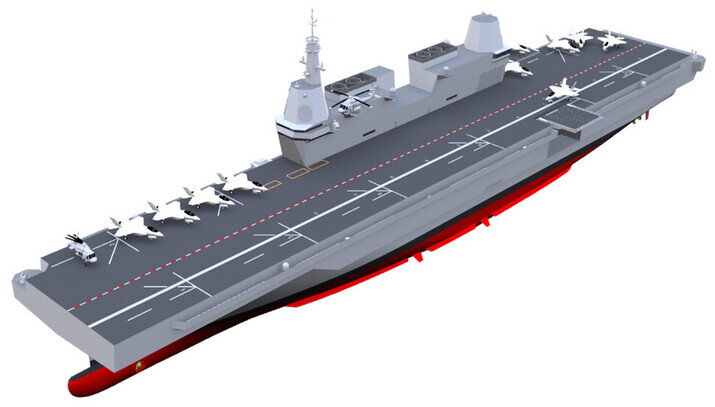

This is not disarmament, but an average annual increase of 6.1%. Over that time, South Korea will overtake Japan in defense spending. As of 2020, South Korea is already ranked sixth in the world for defense capabilities. The price tag is not the only issue, either -- the intermediate-term plan included the firm mention of a “light aircraft carrier” and effectively made official the introduction of nuclear submarines.

Even conservatives calling for “feasibility examination”Both light aircraft carriers and nuclear submarines have long been on the South Korean military’s wish list. The military has consistently argued that the two weapons systems represent the only means of countering the military asymmetry presented by North Korea’s nuclear weapons and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). Aircraft carriers, which are used to launch fighter aircraft, are categorized by full loaded displacement into large (70,000 tons or greater), medium (40,000-70,000 tons) and light (less than 40,000 tons) types. The US currently operates 12 large aircraft carriers with deck lengths alone measuring around 300m. A light aircraft carrier is less than half the size of a large one. In addition to its 67,500-ton medium aircraft carrier Liaoning, China also operates the Shandong in the same class, with plans to possess four large and other aircraft carriers by 2030.

Japan has also been focusing on introducing aircraft carriers. The country has announced plans to renovate its Izumo-class 27,000-ton large helicopter carrier transport vessel into a large aircraft carrier for deployment by 2025. Calls to beef up naval capabilities have been emerging, with Japan’s threatening patrol aircraft flyby of a South Korean naval vessel in December 2018 followed by joint China-Russia patrol flight exercises targeting the US in July of last year. During the latter case, a Russian military aircraft infringed on South Korean territorial airspace around Dokdo.

There are clear reasons why MND has been unable to apply the “aircraft carrier” name to its aircraft carrier project in the past. To begin with, its operational conditions are different from those of China and Japan. With a coastline directly on the Pacific Ocean, Japan has a broad area for naval operations. China similarly has over 10,000km of coastline. Many progressives and conservatives alike have argued that South Korea in comparison has no need for aircraft carriers.

“In terms of the Korean Peninsula and its surrounding waters, bases at Cheongju and Wonju are fine for launching aircraft, giving us little reason to field an aircraft carrier. A light carrier would be particularly inefficient because its F35-B fighters have an operational radius that’s 300km shorter than our F-35As [which have a maximum radius of 1,100km],” said Kim Dong-yeop, a professor at the Kyungnam University Institute for Far Eastern Studies, in a telephone interview with the Hankyoreh on Aug. 11.

Similar criticism has been raised by conservatives, including Dakota Wood, a senior research fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative US think tank. During an interview with Voice of America on Oct. 5, 2019, Wood said that “presenting a very few number of large targets [such as amphibious assault craft and light aircraft carriers] is a bad approach” given the “fairly congested waters on each side of the peninsula.”

During a parliamentary audit of the South Korean Navy in October 2019, Kim Jung-ro, former lawmaker with the United Future Party, even raised questions about the need for a light carrier considering that the country’s current military “is capable of defending the entire Korean Peninsula” and said that the plan’s “feasibility needs to be verified.”

Nevertheless, the aircraft carrier idea is becoming a reality. Even a “light” aircraft carrier, after all, is still a carrier. In American military doctrine, light aircraft carriers are typically used as support for sudden strikes and amphibious operations by the marines, but the light aircraft carrier that South Korea will deploy is likely to focus on air operations involving the F-35B.

The construction cost in the mid-term plan is 1.83 trillion won (US$1.54 billion), but that’s just an estimate. According to a report about the possibility of building the next generation of cutting-edge naval vessels that was drafted in 2015 by a navy task force that handles strategic analysis, testing, and assessment, the carrier would cost 3.15 trillion won (US$2.65 billion) to build — and that amount omits the jet fighters, helicopters, and other weapon systems with which the carrier would be equipped.

The mid-term plan states that the carrier would hold vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) fighters, but the only such fighter that’s currently capable of being deployed is Lockheed Martin’s F-35B, with a per unit price tag of more than US$100 million. Japan is reportedly planning to acquire 20 such fighters for each of its two Izumo-class carriers by 2025.

“Assuming that three fighter wings would be in operation, 12 fighters would be based on the light carrier and four others would be used for training. Acquiring 16 fighters would cost considerably more than 2 trillion won [US$1.68 billion],” explained a former member of the military who is familiar with the light aircraft carrier project.

When the cost of acquiring helicopters is added to the aircraft and the carrier itself, the total comes close to a whopping 5 trillion won (US$4.21 billion), and that’s not even counting the maintenance cost, which is expected to be a tenth of the total. But critics object that the carrier project doesn’t even have a clear purpose. According to the mid-term plan, the carrier would be designed to “take the initiative in responding to the full spectrum of threats, including transnational and nonmilitary threats, and protect shipping lanes both in waters close to the Korean Peninsula and further out at sea.”

“Considering that our current military strength is capable of deterring threats from our neighbors, it’s unclear what operations would be undertaken by a light carrier. Since a light carrier is vulnerable to attack, it would actually require the acquisition of more destroyers and other military assets. This project would involve a huge military buildup, but there hasn’t been a public debate about it,” said Cheong Wook-sik, director of the Peace Network.

Possession of carriers could spark future conflicts because they’re offensive, not defensiveOther analysts say that a light aircraft carrier could spark conflict in the future because it’s not a defensive but an offensive military asset, which is also true of the F-35B fighters that would likely be based on it. That means that once the carrier is launched and initiates operations, it would inevitably spark confrontations with Korea’s neighbors.

“It’s inconceivable that we would engage in an arms race with China, and the same is true of Japan. [The light aircraft carrier and similar projects] are supposed to make China take us seriously and enable us to deter North Korea while also protecting Dokdo from Japan. But no one seems to be thinking about the military tensions that would be provoked [during the operation of those weapon systems,” said Lee Hea-jeong, a professor at Chung-Ang University.

“Acquiring various weapons systems increases the likelihood that we will be entangled in the US’ strategy of containing China,” said Kim Jong-dae, former lawmaker for the Justice Party.

The absolute benefits of peace and the need for diplomatic solutionsEven if threats arise, they’re unlikely to be solved by acquiring more military assets such as light aircraft carriers or nuclear-powered submarines. Korea’s national interest would best be served by finding diplomatic solutions to disputes with China and Japan over the islets of Dokdo and the underwater reef of Ieodo.

“We need to take into account the absolute benefits that would be brought by peace, whether we’re talking about North Korea, China, or Japan. Rather than a military buildup, therefore, we need to be working to reinforce peace mechanisms in East Asia, according to the Moon Jae-in administration’s original plan,” Lee Hea-jeong explained.

Others argue that an aircraft carrier wouldn’t even be necessary for the MND’s goal of protecting shipping lanes, a goal that could be adequately performed by South Korea’s current force of destroyers and submarines.

“The purpose of an aircraft carrier isn’t acquiring shipping lanes but seizing air superiority. Furthermore, an aircraft carrier isn’t capable of operating on its own but has to be escorted by a defensive convoy, which makes it inappropriate for protecting shipping lanes,” said Hwang Soo-young, manager of the Center for Peace and Disarmament at People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy.

Nuclear submarines are inappropriate for S. Korea’s defense needsNuclear submarines, which are propelled by nuclear energy, have also become a target for criticism. While the term “nuclear” doesn’t appear in the current mid-term defense plan, there is a phrase about “building 3,600-ton and 4,000-ton submarines with improved capacity for navigating underwater and carrying weapons.”

“At the current stage, it would be inappropriate [to call them nuclear submarines]. There will be an opportunity to talk about that at the appropriate time,” the MND said.

But despite this ambiguous response, the construction of nuclear submarines is being treated as a fait accompli, just like the light aircraft carrier. Shortly after North Korea’s successful test of a submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) in 2016, South Korea’s conservative camp touted nuclear submarines as a weapon system capable of monitoring and tracking North Korean submarines equipped with SLBMs. Compared to the North’s diesel submarines, nuclear submarines are superior both in speed and underwater navigation ability.

Theoretically, nuclear submarines don’t need to be refueled, which means that they can continue monitoring enemy submarines without rising to the surface. Nuclear submarines are also more than three times faster than diesel submarines, giving them an edge in detecting and tracking North Korean submarines awaiting deployment.

Nuclear submarines were a campaign pledge made both by President Moon Jae-in and by the ruling Democratic Party. A Q&A paper about nuclear submarines published in October 2017 by the Institute for Democracy, which serves as the party’s in-house policy think tank, described the submarines as the “most practical deterrent against North Korea’s SLBMs.”

Even though nuclear submarines have superior capabilities to South Korea’s current submarine fleet, the debate about their actual effectiveness goes back even further than the debate about light aircraft carriers. That debate begins with doubts about whether high-performance nuclear submarines, which are expected to cost about 1.5 trillion won (US$1.26 billion) a piece, are appropriate for South Korea’s zone of operations.

“Since even a high-performance nuclear submarine can only detect another craft within a distance of 10km, keeping tabs on North Korea’s submarines would mean that South Korea’s submarines are entering North Korean territorial waters. That itself could create a problem,” explained Kim Dong-yeop.

Even if South Korea’s nuclear submarines can detect and track movements by North Korea’s submarines, it would be impossible to know for certain whether those submarines are equipped with SLBMs or whether they’re targeting South Korea. Such activities could even conceivably trigger a conflict that would not otherwise have arisen.

And the very advantages of nuclear submarines could turn out to be downsides. For instance, nuclear submarines can’t mute the noise produced by their nuclear propulsion system, including the reduction gearing on their turbines. The problem is that the nuclear reactor can’t be shut down. In contrast, a diesel submarine can turn off its engine to enable silent maneuvering. The conditions on the battlefield would ultimately determine which type of submarine holds the upper hand.

South Korea’s biggest military buildup in history needs to be adjustedNuclear submarines present yet another challenge: there’s no guarantee that the development process would go smoothly. Even if South Korea manages to avoid violating the Non-Proliferation Treaty and the International Atomic Energy Agency Safeguards by using uranium with an enrichment of less than 20%, another hurdle is the South Korea-US Agreement for Peaceful Nuclear Cooperation, which bans South Korea from using nuclear power for any military purposes.

Granted, Kim Hyun-chong, second deputy director of South Korea’s National Security Office, said that Seoul’s nuclear agreement with Washington is “completely separate and bears no relation” to nuclear submarines, which could imply that the two sides have already reached an understanding on that issue. But even aside from that, the Moon administration could face criticism for its aggressive support of nuclear submarines, which clashes with its current support for a nuclear phase-out.

In his Liberation Day address on Aug. 15, Moon addressed not only South Korea’s relationship with Japan but also inter-Korean relations and the overall accomplishments of his administration. And in last year’s speech, Moon expressed his desire to build the “peace economy,” creating prosperity through peace, and to complete Korea’s liberation through the reunification of the country.

But one day after last year’s speech, North Korea’s Committee for the Peaceful Reunification of the Country released a statement declaring that the North had “nothing more to say to the South Korean authorities and no intention of sitting down with them again.” Why would North Korea have made such comments?

In July, North Korean leader Kim Jong-un asked South Korea to stop acquiring cutting-edge weaponry and to halt its joint military exercises with the US. But those exercises were ultimately continued on Aug. 11, and the MND released its mid-term plan, predicting 291 trillion won (US$254.1 billion) in defense spending, on Aug. 14. At least as far as the mid-term plan is concerned, nothing has changed in regard to the construction of a light aircraft carrier and nuclear submarines.

“It’s not easy to normalize inter-Korean relations and the Korean Peninsula Peace Process while we continue our biggest military buildup in history. It’s time for an adjustment,” said Jeong Uk-sik.

By Ha Eo-young, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0430/9417144634983596.jpg) [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis![[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track? [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0430/1617144616798244.jpg) [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

Most viewed articles

- 1First meeting between Yoon, Lee in 2 years ends without compromise or agreement

- 2[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- 3After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 4Under conservative chief, Korea’s TRC brands teenage wartime massacre victims as traitors

- 5‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 6Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 7[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- 8Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 9Dermatology, plastic surgery drove record medical tourism to Korea in 2023

- 10Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors