hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Records show how America stood back and watched as Gwangju was martyred for Korean democracy

From the fall of 1979 to the spring of the following year, South Korea was plunged into political chaos. President Park Chung-hee was assassinated on Oct. 26, concluding an 18-year dictatorship. Chun Doo-hwan led another coup less than two months later, marking the advent of a new era of authoritarianism.

Under Chun’s rule, Koreans grew hungrier for democracy than ever, sparking the May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement, which was met with slaughter and suppression by his junta. Chun’s new military regime and its supporters quickly secured power, and the government was essentially its puppet.

During a national Cabinet meeting on May 17, 1980, the government, under the yoke of Chun’s regime, approved an order that declared martial law over the entire country. Nationwide, universities were ordered to suspend classes. Troops flooded onto campuses to enforce martial law. On May 17, 1980, Chun dispatched two battalions of the ROK Airborne Brigade to suppress a citywide movement of students and activists who opposed his regime. The operation, codenamed “Splendid Holiday,” was the bloody culmination of Chun’s ruthless rise to power.

Outside the Korean Peninsula, an entity observed the aforementioned events as if they were unfolding in a game: the United States of America. The US Embassy in Seoul and the military intelligence agencies of US troops in Korea meticulously observed the political upheavals of South Korea, and reported updates to authorities in Washington — almost in real time.

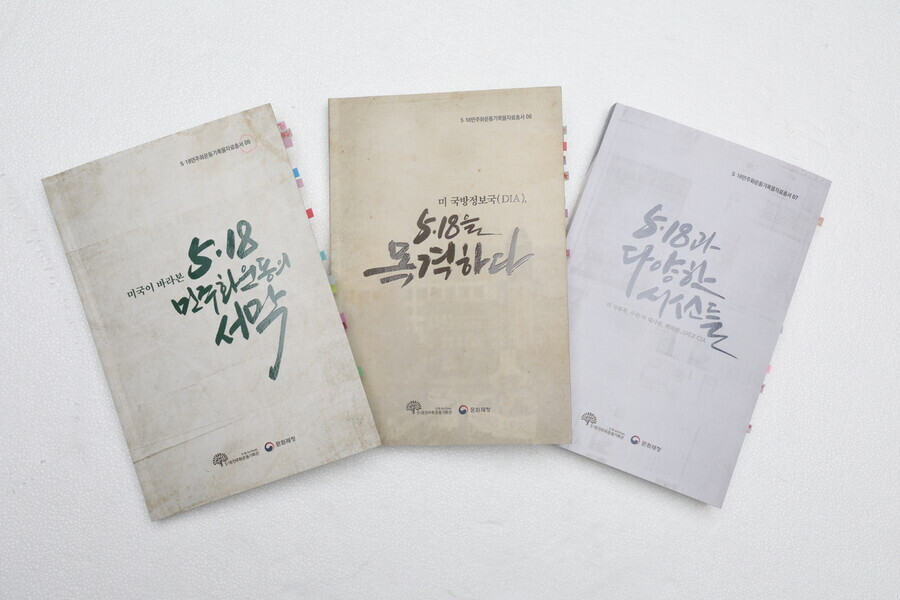

Last year, the 5.18 Archives published an anthology of documents and materials related to the massacre in Gwangju. Volumes 5-7 focus on the raw facts pertaining to America’s stance and response to South Korea’s political upheavals. After Park Chung-hee was assassination on Oct. 26, 1979, US authorities quickly moved to convene a Policy Review Committee for Korea. From then onward, the relevant agencies and entities provided sensitive intelligence on Korea to Washington.

American journalist Tim Shorrock obtained declassified documents from this era and shared them with the world from 1993 to 1995. A portion of these were reported by domestic news outlets at the time, but the aforementioned anthology offers the first full and detailed translation of the documents.

Shorrock organized the documents chronologically and by subject matter. He also categorized them according to the agencies that drafted them: the White House, the Department of State, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the US Embassy in Seoul. He submitted all his findings to the 5.18 Archives in 2017. It was a massive tranche of documents: 16 boxes, 1,256 documents, 3,530 pages. The 5.18 Archives immediately began translating them. Staying true to Shorrock’s original classifications, the archives turned out three volumes, featuring the original US documents on the left and a faithful, complete translation on the right.

Volume 5 of the archives’ anthology, “The US Perspective on the 5.18 Gwangju Democratization Movement,” contains documents drafted during the time period from the Dec. 12 military coup to the May 18 movement in Gwangju. Volume 6, “The DIA Witnessed the Gwangju Massacre,” contains DIA documents drafted during the protests in the former provincial capital, from May 18 to 17.

Volume 7, entitled “May 18 and Different Perspectives,” compiles documents showing assessments of the overall situation in South Korea at the time of the incident, as well as the more general political situation in East Asia, by key US institutions such as the State Department, the US Embassy in Seoul, the White House, and the Central Intelligence Agency.

Plans in the military for the Hanahoe’s removal after Dec. 1979 coup

The books contain a great deal of notable information, including episodes that have not been widely known about to date. The US observed developments closely from the very start of the December 1979 coup and understood their significance.

Consider the following passages from a document sent by the State Department on the evening of Dec. 12 to the White House, US Embassy, UN Commander in South Korea (USFK), and the US Defense Department, among others, under the title “Military Power Play in South Korea.”

“3. In the early evening hours December 12 Seoul time (early morning Washington time), a group of ROK Army officers centered apparently on Defense Security Force commander General Chon Tu-hwan [. . .] arrested Army Chief of Staff and martial law commander General Chung Sung-hwa. [. . .] In the process a few shots were fired near military headquarters in south central Seoul (Yongsan) but no deaths have been reported.”

“6. Three demands have now been conveyed privately from the incipient coup forces. These are replacement of the martial law commander, replacement of the Third ROK Army commander, and replacement of one lesser official. While these demands seem limited [. . .] any dictation of the appointment of the martial law commander would effect a major power grab.”

Also interesting are reports of moves within the South Korean military to remove the Chun clique in the wake of the coup. A report drafted by an agent with the US Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) on Jan. 9 states:

“A. [Redacted] source indicates that some senior members of the ROKAF and ROK Navy are considering counter actions against HG Chon Tu Hwan, the architect of the 12-13 Dec 79 Army takeover and the click which shpports [sic] him if he does not step down or if his power is not curbed in someway. [. . .] [I]f Chon Tu Hwan continues to exert unwarranted pressure on the Choi government [. . .] counter actions are being planned which would use ROK Marine Corps forces to remove (arrest) the clique from power.”

William Gleysteen, the US ambassador in Seoul, shared his own views while maintaining close contact with Assistant Secretary of State for Asia Richard Holbrook, the top working level official in US policies concerning the Korean Peninsula. Gleysteen made no secret of his negative attitude toward the military administration, refusing to meet with Chun for some time in the wake of the December 1979 coup. He also shared opinions numerous times expressing concerns about Chun’s behavior and calling for restraint by all political forces.

Over time, however, the deteriorating situation overtook him, and he began leaning toward acknowledgment of the Chun regime in the name of South Korean stability and US interests. For the most part, this ended up reflected in US policies.

In a policy assessment document dated Jan. 29, 1980, Gleysteen wrote, “Basic U.S. interests in Korea remain unchanged, but [. . .] [w]e find ourselves in an unprecedentedly activist role. [. . .] [E]ventually we will be ‘damned if we do and damned if we don’t’ by various elements of society seeking our support.”

Military regime inflates possibility of N. Korean invasion

On May 7, 1980, at a moment when the “Seoul Spring” hopes had been dashed and the military regime’s power grab scenario was reaching its final stages, Gleysteen sent a cable to Holbrook under the title “Korea Focus-Informal Policy Review.”

“My one sentence reply to several of your questions,” he wrote, “is that (A) our basic political objective should be to help bring about whatever degree of political relaxation is necessary for the maintenance of political stability, leaving to the Koreans the question of deciding how much relaxation is required and how it is to be accomplished [and] (B) re Chun Doo Hwan [. . .] our objective should be to slow him down so he does not go beyond what the Korean people — and even the Korean military — consider tolerable.”

Cables exchanged by Gleysteen and the State Department that day and the following one seemed to suggest that the US might turn a blind eye to the Chun regime’s bloody suppression of the public.

In another May 7 cable to Holbrook under the title “ROKG shifts special forces units,” Gleysteen wrote, “2. ROK military has advised U.S. command of following troop movements for contingency purposes. On May 8 the 13th Special Forces Brigade [. . .] will be moved to the Special Warfare Center southwest of Seoul for temporary duty. On May 10 the 11th Special Forces Brigade [. . .] will be moved to the Kimpo Peninsula and co-located for temporary duty with the First Special Forces Brigade.”

“3. U.S. Command also alerted to the possibility that the First ROK Marine Division in Pohang might be needed in the Taejon/Pusan area. First Marine Division is OPCON to CFC and U.S. approval would be required for movement. [. . .] CINCUNC would agree if asked.”

The following day, on May 8, the US Statement sent a cable to Gleysteen in South Korea in the name of Holbrook’s direct superior, Deputy Secretary of State Warren Christopher, stating, “We agree that we should not oppose ROK contingency plants to maintain law and order.”

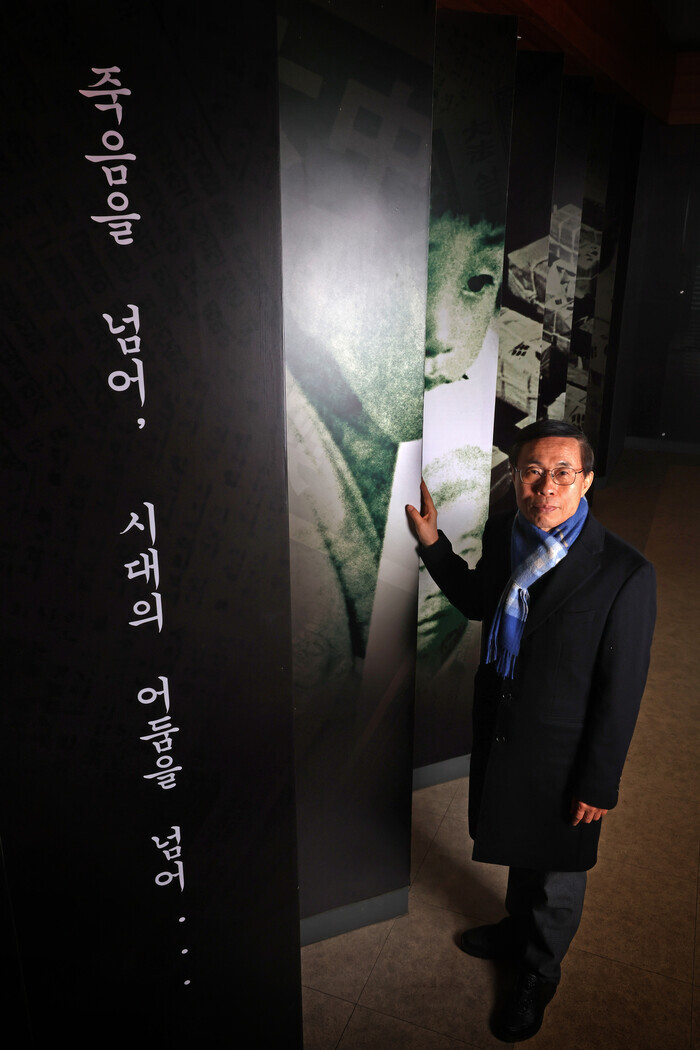

Lee Jae-eui, an expert committee member with the May 18 Democratization Movement Truth Commission, commented, “This could be seen as the first document where the US internally recognized officially that the Chun Doo-hwan regime was mobilizing the military to suppress the pro-democracy demonstrations.”

Calling this the “most important inflection point” for America’s attitude toward the coup in South Korea, Lee added, “When Gleysteen met with Chun Doo-hwan the following day on May 9 and told him about the US policy, Chun was jubilant.”

“On May 10, Chun’s camp acquired a Japanese document through the Korean Central Intelligence Agency [predecessor of today’s National Intelligence Service] that mentioned the ‘possibility of a southern invasion by North Korean forces,’ which was reported in inflated fashion to Prime Minister Shin Hyun-hwak during a Cabinet meeting on May 12,” he explained.

“At that point, the regime’s mood began shifting toward a sense that the demonstration could no longer be ‘left unaddressed,’” he said.

Gleysteen and the US State Department continued closely exchanging information and coordinating opinions afterwards. On May 17, with emergency martial law having been expanded throughout South Korea, Gleysteen sent home a cable titled “Crackdown in Seoul.”

In it, he wrote: “2. The Korean military leadership [redacted] has ignored legitimate authority in the ROKG to institute a tough crackdown on students and probably the entire political spectrum. An all but formal military takeover may be in process.”

“3. [. . .] [W]e were told [. . .] that ‘extraordinary martial law’ would be imposed throughout Korea (including Cheju Island), technically meaning that the martial law commander reports directly to the President rather than to the Defense Minister but in substance that the military have an even freer hand.”

“4. We were given no repeat no notification of these decisions. [. . .] Reportedly, the military leaders were extremely unhappy over what they regarded as excessively soft tactics by the government toward the students this past week.”

“9. [. . .] I do not think we can avoid a public statement [. . . .] [I b]elieve I should be instructed on the highest authority to call on President Choi and probably the Minister of Defense and martial law commander to make a representation along the following lines.”

The “instructions” that Gleysteen requested came the very day with a statement at 1 pm on May 18 (US time) credited to a State Department spokesperson.

“We are deeply disturbed by the extension of martial law throughout the Republic of Korea, the closing of schools, and the arrest of a number of political and student leaders. [. . .] We urge all elements in Korean society to act with restraint at this difficult time. [. . .] [T]he U.S. government will react strongly to any external attempt to exploit the situation in the Republic of Korea.”

US documents on Gwangju situation resemble DSC records

But the ambiguous decisions and response from the US ended up effectively freeing the Chun regime from its shackles. At 1 am on May 18, the Defense Security Command — with Chun as its commander — carried out sudden arrests of major politicians and dissident figures, including Kim Dae-jung and Kim Jong-pil, and seized the National Assembly building in Seoul’s Yeouido area.

A clash that erupted that morning between students and martial law forces at Chonnam National University in Gwangju escalated within just a few hours into a confrontation between the military regime and the city’s people. The situation was touched off by the brutal demonstration suppression tactics and barbaric actions of martial law troops against students and ordinary citizens alike. The uprising in Gwangju had begun.

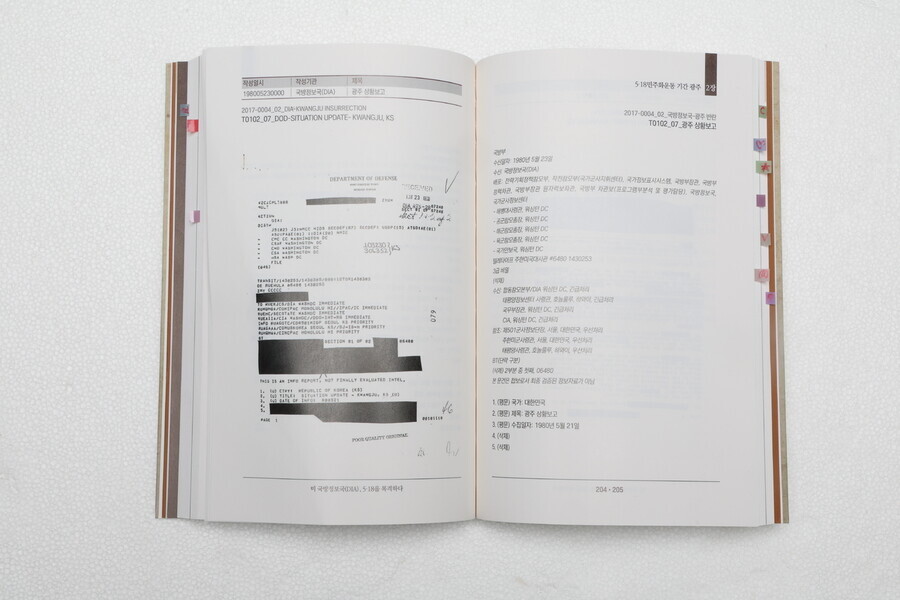

For the second volume in the series, the May 18 Archives specifically selected documents drafted by the US Defense Intelligence Agency, focusing on the Gwangju Uprising and the 10-day period from May 18 to 27, 1980.

Most of the sources for the information have been redacted. But some of the documents appear to have been obtained from collaborations within the South Korean military or be more or less word-for-word English translations of materials supplied by South Korean military intelligence organizations.

One particular example is “Kwangju Riot — Update as of 1000 Hours, 22 May 80,” which provides a detailed real-time record in five- to 10-minute increments of the situation that unfolded over a period starting 45 minutes after the martial law forces opened fire on the public in front of the South Jeolla Provincial Office building at 1 pm on May 21 and continuing until 10 o’clock the next morning — while omitting mention of the actual act of opening fire. The document is almost identical to a daily bulletin drafted at the time by the ROK Army’s Defense Security Command.

“—1345 hours: Among the rioters assembled in front of the provincial government building, an unknown number of adults in their thirtdes [sic], using megaphones, shouted that the “Combat and Training Command and the Defense Security Unit would be assault targets” that night. At that moment, demonstrating rioters cheered loudly.”

“—1505 hours: An unknown number of rioters seized 40 weapons from the Hwasun arms room, and proceeded toward Kwangju.”

“—1628 hours: The rioters captured 150 carbines and 900 rounds of carbine ammunication from the arms room of the Honam Electric Company in downtown Kwangju.”

“—16:50 hours: Airborne troops stationed at the provincial government building withdrew to the Chosen University campus.”

“—1750 hours: Weapons fire is being exchanged between rioters and the martial law troops at Chonnam University. At Chosen University, the martial law troops fired upon rioters.

“—18:10 hours: Announcements are being made to citizens to go back home because there will be “firefights tonight.”

“—20:45 hours: The rioters assembled at Kwangju Park and at the Mutung Stadium [. . .]. They were rumored to be planning to make the provincial government building by force at approximately 2130 hours.”

“—0015 hours: The CAC blocked the routes of access.”

“—0615 hours: High buildings in Kwangju were occupied by armed rioters.”

“—0945 hours: Information became available that the rioters in the general area of Kwangju would disperse toward Wando and other islands based upon the fear that troops of the Special Warfare Group might attack and seize Kwangju.”

Another document entitled “Kwangju Situation Update as of 1200 Hours, 23 May 80,” which was drafted the following day, includes a chilling passage summarizing public sentiment at the time that expresses the anti-communist and anti-North Korean ideology of the South Korean military and US during an era of Cold War confrontation.

“The situation today is somewhat like the Sunch’on-Yosu Rebellion incident. (Translator’s notes: It took place in 1948) The government must be more active in quelling the current situation,” it read.

The US also received advance notification of the martial law forces’ operational plan a day before their suppression of the final uprising at South Jeolla Provincial Office building in the early hours of May 27. This is recorded in a May 26 report entitled “DOD-Plan to Move Troops into Kwangju, Possible Demonstrations in Seoul,” for which the source has been redacted and the DIA and Pacific Air Force command in Hawaii are listed as recipients.

“Troops have moved into the outskirts of Kwangju-si (city) [. . .] and are starting sweep and mop up operations,” it read. “Tonight (26 May 80) or early tomorrow morning (27 May 80), the troops will move into Kwangju enmasse [sic] in an operation to capture and disarm the rioters.”

It also said, “The weapons which the rioters had been turning in were not being turned in to the MLC troops but to the civilian committee trying to work out a settlement. However, the students and hoodlums have now taken them back. Most of the Korea University and Seoul University (SNU) students from Cholla Namdo and many of the students from other universities in Seoul who are from Cholla Namdo have gone down to Kwangju.”

Two days later, on May 29, the martial law forces suppressed the final uprising at South Jeolla Provincial Office. A document from the same day entitled “KN [North Korean] Intentions, Perception in Connection with Kwangju Incident” observes that the perceived North Korean threat during the events of May 18 was groundless and that “LTG Chon [Chun Doo-hwan] tied much of his future to the successful ending of the Kwangju riot.”

“US should apologize to S. Koreans for supporting the Gwangju suppression”

An investigator who took part in the translation and compiling of the series’ fifth through seventh volumes explained, “While translating all the documents donated by Tim Shorrock, I was able to observe the larger currents.”

“The US didn’t have a good grasp on intelligence early on and was concerned about the potential for a North Korean threat amid the disorder. Under the Jimmy Carter administration at the time, the US policy on the Korean Peninsula placed top priority on stability, with democracy coming after that,” they added.

“The initial wave, where they didn’t support Chun Doo-hwan but stood by without getting actively involved, continued as late as the Kim Dae-jung insurrection conspiracy trial. But after a death sentence was handed to Kim Dae-jung [and upheld by the Supreme Court in January 1981], they began pursuing a tradeoff of approval of Chun’s actions for Kim’s life,” they explained.

“A single of that came when they promised to allow Chun Doo-hwan to visit the US and meet with then-President Ronald Reagan [who took office in January 1981],” they added.

Shortly after the series was published, Shorrock shared a message of gratitude to expert committee member Lee Jae-eui, saying he felt honored to see the Gwangju-related documents he had acquired being translated into Korean so that all Koreans could read them.

Shorrock observed that in 1989, when the South Korean National Assembly held its first hearing on Chun’s crimes in Gwangju, the administration of then-US President George H. W. Bush released an extensive white paper on its South Korean policies between 1979 and 1980, which included many discrepancies with what Shorrock himself had heard in Gwangju.

At the end of his message, Shorrock wrote that he hoped to see the US government formally apologizing to the South Korean public at some point for supporting Chun’s suppression of the Gwangju Uprising in May 1980. He also shared a message of respect for the citizens of Gwangju.

By Cho Il-joon, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0509/221715238827911.jpg) [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

[Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea![[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0507/7217150679227807.jpg) [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war- [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

Most viewed articles

- 1[Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- 2‘Free Palestine!’: Anti-war protest wave comes to Korean campuses

- 3Behind-the-times gender change regulations leave trans Koreans in the lurch

- 4Nuclear South Korea? The hidden implication of hints at US troop withdrawal

- 5[Photo] ‘End the genocide in Gaza’: Students in Korea join global anti-war protest wave

- 6Korean president’s jailed mother-in-law approved for parole

- 7In Yoon’s Korea, a government ‘of, by and for prosecutors,’ says civic group

- 8With Naver’s inside director at Line gone, buyout negotiations appear to be well underway

- 960% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 10Yoon’s revival of civil affairs senior secretary criticized as shield against judicial scrutiny