hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

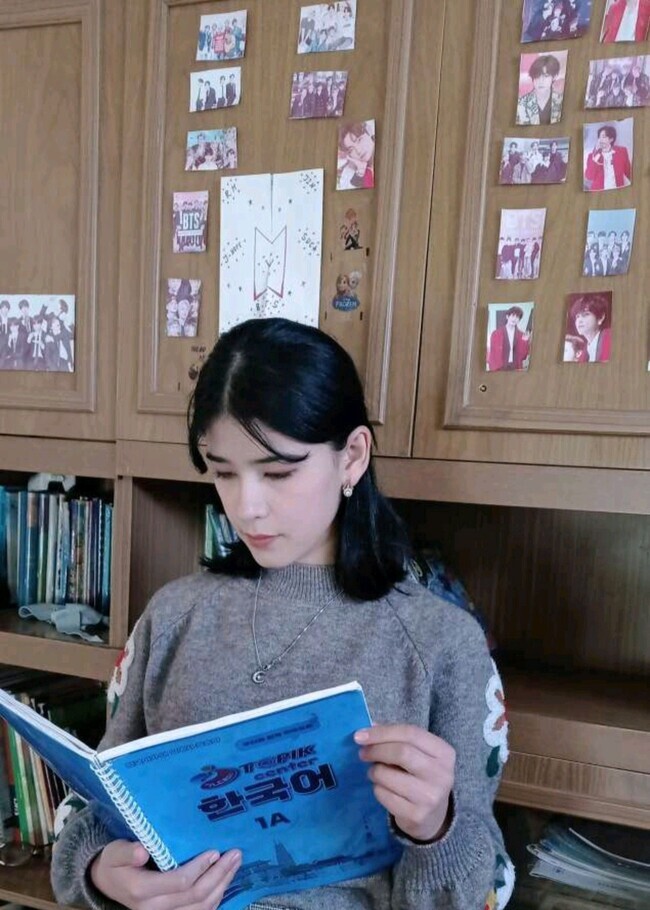

Foreign students rethink Korea as expectations are dashed by harsh realities

Samantha, a 20-year-old studying business management at Mexico’s University of Guadalajara, was shocked after reading about the recent deportation of international students by Hanshin University.

As a huge fan of various K-pop artists such as Baek Ye-rin, DEAN, and PH-1, she was planning to come to South Korea as an exchange student with a goal of eventually ending up working at a Korean hip-hop record label after graduating.

“I know the joy and hopes the Uzbekistan students would’ve harbored when they started studying in South Korea, which only makes it that much sadder,” she told the Hankyoreh.

Samantha had imagined South Korea as a country brimming with opportunities and where diversity was celebrated. “South Korea is a lively, exciting country not only when it comes to education but also in respect to social issues. Since I respect Korean culture, I hoped that South Koreans would also respect my culture and not discriminate against me based on the fact that I am Mexican and Latina,” she said.

But Samantha said that the latest case of a university shipping off more than a dozen international students was not only “unquestionably racist” but also demonstrated that schools “treat their own students like deadweight” when it came to financial issues.

Most international students who come to Korea may be drawn to the country due to their interest in Korean TV series or music, but many also dream of a life in South Korea.

Nguyễn Thị Diệu, a 19-year-old from Vietnam currently attending Myongji University’s Korean Language Education Center, shared, “After completing my language courses, I intend to study further at a Korean university. After graduating from university, I want to become a tour guide and act as a bridge between Vietnam and South Korea.”

Anna, 21, who lives in a small city in East Uzbekistan, is planning on matriculating at Inha University in August 2025. She said that her plan is to major in business management and work for a company in Korea. “I want to live in South Korea until I turn 50,” she told the Hankyoreh.

Such trends are borne out by data. Statistics Korea and the Ministry of Justice released a report from a 2023 survey of immigrant sojourn status and employment on Dec. 18, 2023, which shows that more than six in 10 international students (63%) wish to remain in South Korea after graduation. This number is 8.3 percentage points higher than three years ago.

The number of young foreign nationals living in South Korea has also increased. In particular, the number of foreign nationals aged 15 to 29 has increased to 416,000 in 2023, about 70,000 more than in 2022, when the number was at 347,000. This shows that many people are coming to Korea not for temporary jobs, but with the intention of making a future for themselves here.

However, the country’s systems and culture have not been keeping up with this reality. Restrictions on the types of jobs international students can hold and the complicated visa extension process are also problems, but the quality of education provided to international students is also generally low.

“There are many cases in which we are promised English-taught classes, only for them to be taught in Korean,” said Mukhammadabdullo, a student from Uzbekistan majoring in hotel management. Ultimately this means that international students have to spend more time studying separately for their majors, which puts them in a vicious cycle that gives them less time to study Korean.

International students from Asia, who make up nearly 90% of all international students in South Korea, struggle with high tuition fees and high costs of living. Many say that paying for their health insurance, which is usually around 70,000 to 80,000 won per month, is a “serious dent” in their wallets.

However, these students are unable to work during the day and study at night. The government has banned international students from taking classes after 6 pm as of September 2023. The amount of hours they can work part-time is also restricted to a maximum of 30 hours per week.

Sun Huiling, a 27-year-old graduate student from China, shared, “I wish the Korean government understood the financial difficulties that many international students face.”

Some experts have voiced concerns that the gap between international students’ expectations and the reality they face could mean South Korea fails to establish itself as a sought-after immigration destination.

In particular, some say that while the government bangs on about keeping “outstanding talents” in the country, it has been passive in its support of international students, who can be nurtured into invaluable human resources through education. Instead, the government is only interested in retaining cheap labor by expanding the number of countries covered by the employment permit system and increasing the number of low-skill workers admitted to Korea.

“The government has put forward a blueprint for the establishment of a dedicated immigration agency, but in reality, it is only focusing on policies related to importing labor rather than policies related to immigration,” said Kim Do-gyun, a special professor at Cheju Halla University and expert on immigration policy.

The biggest issue is that international students are now the ones who have to deal with the ramifications of these problems with the administration’s immigration policies in their lives. For foreigners who dreamed of studying in South Korea as a pathway to freedom and opportunities, a country that only treats them as a means to fill the coffers of universities and to provide cheap labor is bound to become less attractive as a destination for studying abroad over time.

Claire, 25, from France, considered coming to Korea to study, but dropped the idea. “After seeing the stifling amount of labor expected of South Korean workers in the media, I don’t think I’ll be able to muster the courage to deal with all that,” she said.

“Koreans worry that more foreign immigrants will mean more competition for jobs, but I think the real problem here are the working conditions in South Korea, which border on exploitation,” she went on.

By Lee Jun-hee, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0517/8117159322045222.jpg) [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later

[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later![[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0516/7417158465908824.jpg) [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence- [Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation

- [Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- [Column] How to win back readers who’ve turned to YouTube for news

- [Column] Welcome to the president’s pity party

- [Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

- [Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- [Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

Most viewed articles

- 1[Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- 2For new generation of Chinese artists, discontent is disobedience

- 3S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 4Xi, Putin ‘oppose acts of military intimidation’ against N. Korea by US in joint statement

- 5[Photo] 1,200 prospective teachers call death of teacher “social manslaughter”

- 6[Exclusive] Unearthed memo suggests Gwangju Uprising missing may have been cremated

- 7N. Korean media upgrades epithet for leader’s daughter from “beloved” to “respected”

- 8[Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

- 9[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner t

- 10[Special reportage- part I] Elderly prostitution at Jongmyo Park