hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

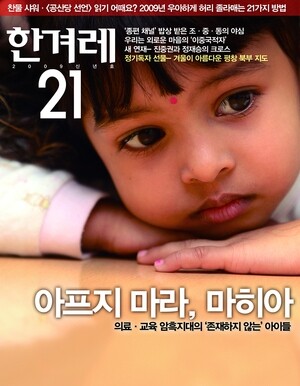

[Reportage] The Bangladeshi child that was deported from Korea

We puttered along in a tom tom, one of the three-wheeled motorbikes beloved among Bangladeshis. It was difficult to keep myself steady as the vehicle changed directions, coming seemingly within inches of colliding with the walls on the curving path. The driver did not slow down. Perhaps he sensed my feelings as I went to see Mahiya for the first time in a decade. I held tightly to the gift package I’d prepared for her to prevent it from tumbling out.

On the afternoon of July 12, the tom tom traveled for some 20 minutes over the muddy side streets of Shonir Akhra, a neighborhood on the outskirts of southern Dhaka. As the straining engine cooled down, The Hankyoreh’s special reporting team got out in front of a single-story house. It was the home of Mahiya, a Bangladeshi girl who was born in South Korea and still considers herself a Bangladeshi-Korean who prefers Korean food to Bengali dishes.

“So you’re Mahiya.” The girl bowed her head slightly and offered a greeting, a shy expression on her face. Gone was the baby fat from years earlier. With her hair cut short, she looked almost boyish. As I presented her with a photograph from her cover story feature in the Hankyoreh 21 from ten years earlier in 2008, she looked at it excitedly.

“Do you remember me?” I asked. She quietly shook her head.

I first met Mahiya on Christmas Eve in Dec. 2008 in the day care center of Shalom House, a facility run by Father Lee Jung-ho at the Maseok Furniture Complex in Gyeonggi Province. Her place of birth was an OB/GYN clinic (identified by the initial J) in Seoul’s Mangu neighborhood, where she was born to father Mukta Hussein, 40, and mother Akhi Jhinuk, 34, who had arrived in South Korea on three-month tourism visas and stayed for over nine years as undocumented migrant workers. The two parents chose the clinic after a friend told them it was good at performing natural childbirth deliveries.

As other gifts, I gave Mahiya some South Korean groceries, including snacks and instant noodles. Her expression was warm.

”True Korean” by age three

“Mahiya still loves Korean food. She hates Bengali food,” explained Jhinuk in clear Korean. “We go to a Korean market here in Bangladesh to buy ingredients and make her galbitang (short rib soup), dakgalbi (spicy stir-fried chicken), and dakdoritang (spicy braised chicken), but it’s expensive.”

By the age of three, Mahiya was already a “true Korean” who loved kimchi and couldn’t get by without tteokbokki (stir-fried rice cakes), eomuk (fish cakes), jajangmyeon (noodles with black bean sauce), or haejangguk (bean sprout hangover soup). But with no nationality to her name, she was not recognized by South Korean society. She could not secure the right to stay in South Korea, to be educated there, or even to access its medical system. Based on her story of discrimination as a “stateless child,” the Hankyoreh 21 published a cover story titled, “Don’t Get Sick, Mahiya.”

An “international orphan” who grew up at the Maseok Furniture Complex for the first eight years of her life, Mahiya finally left for Bangladesh hand-in-hand with her mother in May 2013. She had never been there before. Jhinuk stepped up to the airport’s immigration counter holding the hand of Mahiya’s younger sister Yunfee, who had also been born at J Clinic. The parents had decided that they did not want their innocent children continuing to live as a stateless “illegal sojourners” in South Korea.

Then a second-year student at the Nokchon branch of Sudong Elementary School, Mahiya said, “I don’t know Bengali, and I hate to say goodbye to my friends. I want to keep studying in Korea.” In the end, though, she had to board the plane. (The story was published on the front page of the Hankyoreh’s edition on May 9, 2013.) The following year, father Mukta decided to join his family in Dhaka, putting an end to 16 difficult years as an undocumented migrant worker living in fear of arrest and deportation.

Mahiya’s parents arranged a tutor for their daughter, who did not know how to speak Bengali.

“She was crying so much, saying, ‘I can’t speak Bengali,’” recalled Jhinuk. “So we taught her Bengali by writing the pronunciations in the Korean alphabet underneath the Bengali script.”

Mahiya is now an excellent student who ranks second out of 102 students in her second-year class at a nearby private middle school, her beaming parents added.

She also seemed to have lost some of her Korean ability. Explaining that she had taken her last final the day before, she said, “I think I got everything right on the English test.”

“I’m confident,” she added in fluent Bengali.

Mahiya had changed her life goals, after her childhood dreams of becoming a pediatrician treating poor children like herself. Her new goal, she said, was to become an airline pilot.

“I’m attracted to traveling to different countries,” she said.

The biggest focus of attention for Mahiya’s parents was same as anyone raising a child: education.

“Mahiya goes to cram schools now for English and math. It costs the equivalent of 200,000 won (US$180) a month to send her to cram schools on top of the private middle school,” her mother said.

“There’s an even more expensive private school, which we can’t afford. Her father isn’t working.”

Upon his return in 2014, Mukta opened a shoe store with the money he’d saved in South Korea; he finally closed it in 2017 after three years.

“It failed because I’d only ever done factory work in Korea, and I’d never done business,” he said.

The family is still doing well enough to survive in the neighborhood. In addition to their current home, they also purchased a store in a large Dhaka shopping center with the money Mukta earned doing difficult and unhealthy painting work at the Maseok complex. They earn the equivalent of 100,000 won (US$89) a month on top of that from renting out places in a nearby four-room house. With Mukta not really involved in any work at the moment, Jhinuk has been nudging him to return to South Korea and work at the Maseok complex again. Given his history as an illegal resident there, it would be a tall order.

I asked Mahiya whether she remembered leaving South Korea. It was a mistake. Tears began pouring from her eyes and did not stop. After a little while, she collected herself and said, “I think a lot about my school in Nokchon, and my friends there like Jeong-seon, who used to study with me. I miss Korea. Korea is the country where I was born.”

While Mahiya may view South Korea as “her country,” it remains hard-hearted in its treatment of children like her. It provides only partial access to education and healthcare and is stingy about offering opportunities to stay. A repeated cycle has taken shape where legislation to guarantee the rights of migrant children is presented at the start of each new National Assembly session, only to expire automatically by the time that session closes.

In the case of the 19th National Assembly, lawmaker Lee Jasmine from the Saenuri Party sponsored a bill to recognize “special sojourn” status for migrant children like Mahiya who meet certain conditions; it too ended up expiring. Local groups estimated around 4,000 children of undocumented migrant workers in South Korea at the time Mahiya left. No official statistics are available – and no improvements have been made to the system.

US President Donald Trump, who has adopted an ultra-hard line in his policies on illegal immigrants, introduced measures in May to segregate underage children who had entered illegally with their parents while trials were taking place; a month later, he overturned the measures. Is there anything South Korea can spare for children like Mahiya who were born in South Korea and come to love it? In a situation where the Mahiyas in our midst are being driven out, is it more natural for its people to adopt exclusionary attitudes toward the new asylum seekers arriving here? As a citizen of a “racially homogeneous nation,” these were the questions that kept swirling through my head as I left Mahiya’s house around sunset.

By Jeon Jong-hwi , staff writer from Dhaka

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0517/8117159322045222.jpg) [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later

[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later![[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0516/7417158465908824.jpg) [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence- [Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation

- [Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- [Column] How to win back readers who’ve turned to YouTube for news

- [Column] Welcome to the president’s pity party

- [Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

- [Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- [Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

Most viewed articles

- 1[Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- 2[Exclusive] Unearthed memo suggests Gwangju Uprising missing may have been cremated

- 3[Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- 4[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

- 5‘Shot, stabbed, piled on a truck’: Mystery of missing dead at Gwangju Prison

- 6S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 7[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner t

- 8US has always pulled troops from Korea unilaterally — is Yoon prepared for it to happen again?

- 9China calls US tariffs ‘madness,’ warns of full-on trade conflict

- 10Seoul government announces comprehensive measures to prevent lonely deaths