hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

At crossroads of fundamental change, Seoul is overlooking history in favor of military cooperation with US, Japan

The relationship between South Korea and Japan is likely to undergo a “fundamental change” following a trilateral summit with the US at Camp David on Aug. 18, as indicated by US President Joe Biden last weekend.

Seoul and Tokyo’s relationship is expected to be upgraded to a “quasi-alliance” in which they cooperate on a military level to pressure China and contain North Korea. The two countries have never cooperated on that level since they normalized diplomatic relations in 1965.

There are concerns that demands for a just resolution to historical issues will be disregarded in that process.

Following 35 years of Japanese rule, South Korea began talks to normalize diplomatic relations with its former colonial overlord in October 1951, when the flames of war still raged on the Korean Peninsula.

The Korean War, which broke out soon after World War II, pitted the US against the Communist bloc of North Korea, China and the Soviet Union (today’s Russia). The US sought to level the playing field by quickly normalizing South Korea’s relationship with Japan.

But it wasn’t easy to surmount Korea and Japan’s historical grudge. The two sides finally agreed to normalize relations in June 1965, following 13 years and 8 months of drawn-out negotiations.

Japan agreed to aid South Korea’s economic development by providing US$300 million in grants and US$200 million in loans to cover any outstanding claims. But the two countries glossed over fundamental historical issues, such as the question of whether Japan’s colonial rule of Korea had been legal or illegal.

But owing to a combination of South Korea’s deep-seated distrust of Japanese military expansion and Japan’s own pacifist constitution, which renounces the possession of a military and the right of belligerency, relations between the two sides remained fundamentally confined to an “economic cooperation” framework.

Military cooperation would eventually come about through US mediation with the South Korea-US Mutual Defense Treaty in 1954 and the US-Japan Security Treaty in 1952. For Washington, trilateral military cooperation with Seoul and Tokyo has been a long-awaited development that has been delayed by over half a century.

The situation began shifting around the end of the Cold War in late 1989. It was during this period that survivors of sexual slavery by the Japanese military and other colonization-era victims began speaking out in earnest.

Japan responded in 1993 with the Kono Statement, which acknowledged military involvement in the “comfort women” issue and acknowledged the forcible nature of the mobilization process, and in 1995 with the Murayama Statement, which expressed a message of apology and remorse for Japan’s past colonization and acts of aggression.

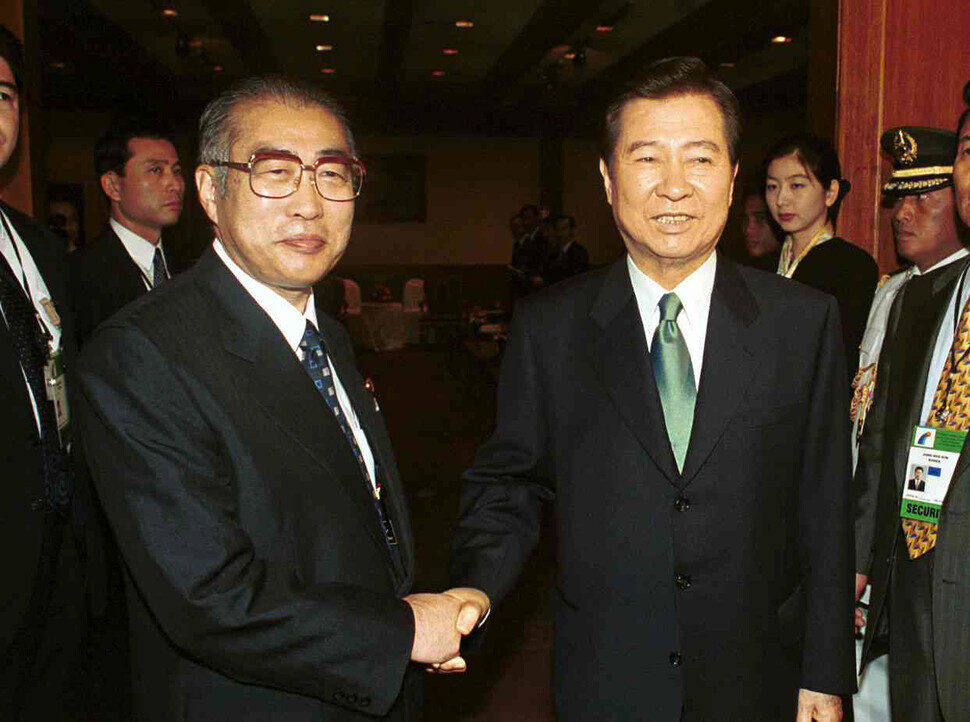

It was on the basis of this reflective historical attitude by Tokyo that South Korea and Japan were able to agree on a 1998 Joint Declaration acknowledging each other as equal partners. This was followed by a period of full-scale cultural interchange between the two sides, including a Korean Wave boom in Japan.

But the “good old days” between them came to an end with a rapid shift that occurred during the 2010s. Some of the ominous changes that occurred included troubling developments with the North Korean nuclear issue, the rise of China, and a lurch to the right in Japan — as symbolized by the reelection of the late Shinzo Abe (1954–2022) as prime minister.

In the areas of history and national security, Abe changed the very face of postwar Japan. In August 2015, Abe declared, “We must not let our children, grandchildren, and even further generations to come, who have nothing to do with that war, be predestined to apologize.”

In terms of security policy, an amendment of the Guidelines for US-Japan Defense Cooperation in April 2015 upgraded the two sides’ relationship into a “global alliance.”

In December 2022, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida amended three security-related documents to establish plans for Japan to acquire “enemy base strike capabilities” — meaning the possibility for a preemptive strike against North Korea or China. It was a devastating blow to the “exclusive defense” principle that had been sustaining Japan’s pacifist constitution.

After coming to office in May 2022, South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol announced what’s been panned as a “concession plan” on March 6 of this year, which effectively neutralized a Supreme Court of Korea ruling from October 2018 holding Japanese companies responsible for compensating victims of forced labor mobilization. This represented a step backward from Seoul on historical issues.

Earlier, in a speech commemorating the March 1 Independence Movement, Yoon had declared trilateral cooperation among South Korea, the United States and Japan to be “more important than ever to overcome the security crises including North Korea’s growing nuclear threats and the global polycrisis.” In essence, the president opted to take the first step toward a three-way alliance that all preceding Blue Houses had been wary of for the past 70 years.

On Tuesday, the Financial Times reported that at the summit slated for Aug. 18, the US would be pursuing a “historic” joint statement that would require consultations in the event of an attack on any of the three countries. It was also reported that there are discussions about setting up a hotline between the three heads of state.

If all this comes to pass as is, the upcoming Camp David summit will likely be remembered as a decisive turning point in which Korea chose to forget its history and head for trilateral military cooperation with the US and Japan.

By Gil Yun-hyung, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0517/8117159322045222.jpg) [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later

[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later![[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0516/7417158465908824.jpg) [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence- [Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation

- [Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- [Column] How to win back readers who’ve turned to YouTube for news

- [Column] Welcome to the president’s pity party

- [Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

- [Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- [Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

Most viewed articles

- 1Celine Song says she’s gratified global audiences have responded to the kismet of ‘inyeon’

- 2[Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- 3[Exclusive] Unearthed memo suggests Gwangju Uprising missing may have been cremated

- 4[Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- 5Xi, Putin ‘oppose acts of military intimidation’ against N. Korea by US in joint statement

- 6Truth commission confirms Korean War killings by soldiers and police

- 7USFK sprayed defoliant from 1955 to 1995, new testimony suggests

- 8[Editorial] South Korean women are mobilizing in unprecedented ways

- 9Calls for gender-equality continue as demonstrations target President Moon

- 10[Column] “Hoesik” as ritual of hierarchical obedience