hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] “Who gave the order to shoot my husband?”

“He worked so hard dragging that cart around and then ended up dying in the Gwangju Democratization Movement,” said Jeong Gwi-sun, who spoke with the Hankyoreh at her house in the Munheung neighborhood of Gwangju’s Buk (North) District on May 13.

When our conversation turned to the Gwangju movement, which began on May 18, 1980, the first thing this 78-year-old woman did was sigh. Jeong’s husband Kim Man-du, born in 1936, was shot by a paratrooper in front of Gwangju Station on the night of May 20. Kim was transported to the hospital, where he died, three days later.

Kim suffered his fatal injury while participating in a demonstration in front of Gwangju Station to denounce the soldiers’ atrocities. “My husband was shot and killed, but no one has ever found out who gave the order to fire,” Jeong said.

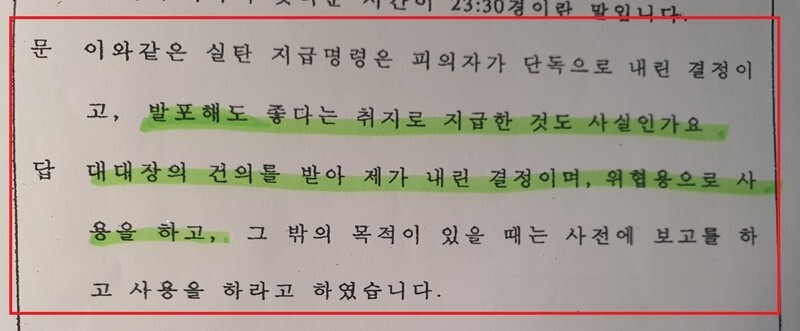

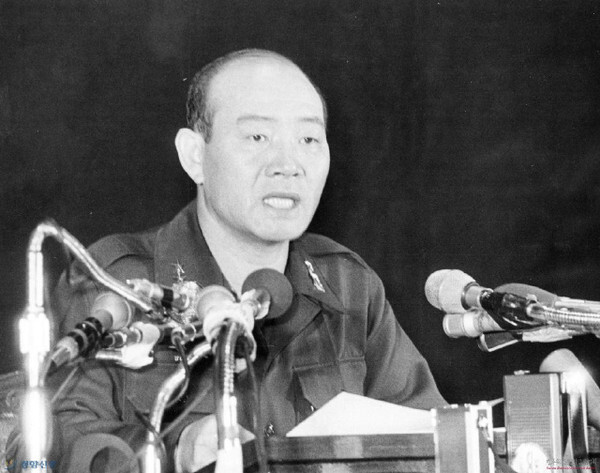

The unit that fired the first volley at the protesters in front of Gwangju Station was the 3rd Airborne Brigade, which was deployed to the city on May 20, 1980. On Jan. 17, 1996, prosecutors who were investigating the military coup on Dec. 12, 1979, and the Gwangju Democratization Movement asked Choe Se-chang, 86, who’d been the commander of the 3rd Airborne Brigade, whether he’d made the decision to provide the soldiers with live ammunition on his own accord and whether the soldiers had been given the rounds with the understanding that they could open fire. Choe responded by saying that he’d made the decision on the advice of the battalion commanders and that he’d told them the rounds were supposed to be used for warning shots and that was to be briefed in advance before they were used for any other purpose.

Choe was a key member of the Hanahoe secret officers’ club that was led by Chun Doo-hwan, head of the Defense Security Command. Choe had participated in the Dec. 12 coup and went on to enjoy a brilliant career during the presidencies of Chun Doo-hwan and Noh Tae-woo, serving as commander of the 1st Corps, commander of the 3rd Army, chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and ultimately Minister of National Defense.

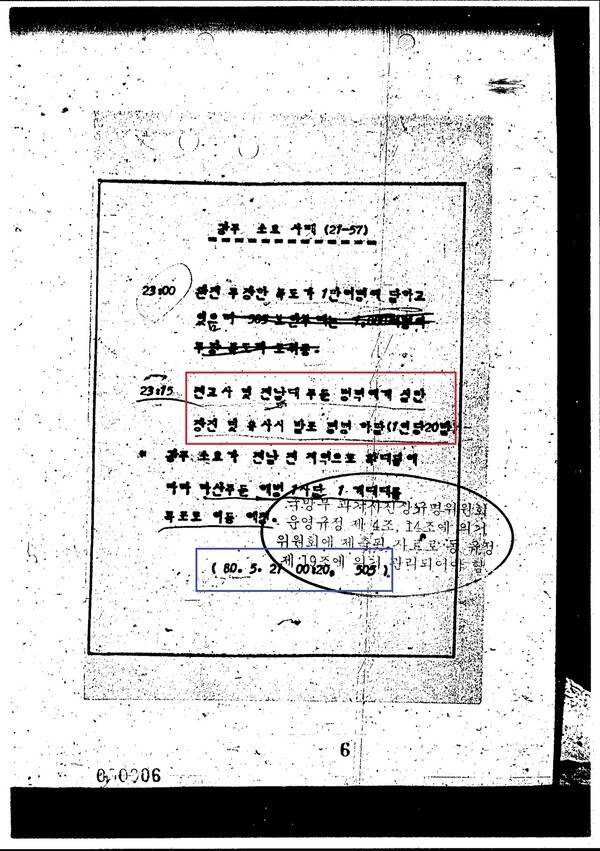

A classified document called the “Gwangju Riot,” which appears to have been composed by the 505 Security Unit in Gwangju, contains the phrase, “Issued order to open fire (20 rounds per soldier),” indicating that such an order was given. The document was composed at “0020 May 21,” or 20 minutes past midnight, which shows that the order was given on the evening of May 20.

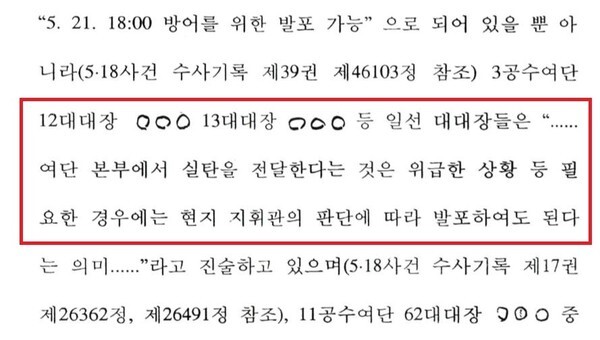

Unit commanders at the time understood the provision of live rounds to be an order to fire. Battalion commanders who were in the thick of things during the movement told investigating prosecutors that “the distribution of live rounds from the brigade headquarters meant that we could open fire if an emergency made that necessary.”

“At 9:30 pm on May 20, the brigade commander [Choe Se-chang], who was standing next to a street in the campus of Chonnam University, pointed to a box of ammunition on the back of a 2.5 ton truck and told me to deliver it to the 11th Battalion and then report back,” said Yun Su-ung, a major who was serving as assistant chief of staff for intelligence for the 3rd Airborne Brigade. The first volley of bullets in front of Gwangju Station claimed the lives of five citizens: Kim Man-du, along with Kim Jae-hwa (25), Kim Jae-su (25), Lee Buk-il (28), and Park Se-geun (36).

Military leaders say soldiers only fired “warning shots”The leaders of the military junta have only acknowledged that the soldiers fired warning shots. “At 11:30 pm on May 20, Lieutenant Colonel Park Jong-gyu [head of the 15th Battalion] fired the seven rounds in his pistol into the air as a show of force,” Choe Se-chang testified.

Kim Jong-heon, a major serving as assistant chief of staff for operations in the 3rd Airborne Brigade, told prosecutors that he’d been approaching Gwangju Station Intersection while taking live ammunition to Gwangju Station when he’d suddenly heard gunshots behind him. “I pulled out my pistol too and fired several rounds into the air,” Kim said. While the shots that airborne troops fired in front of Gwangju High School on May 19 were largely intended to serve as a warning, the volley of gunfire in front of Gwangju Station on May 20 signified something else.

Early in the morning on May 21, following that first volley at Gwangju Station, Korea’s Martial Law Command basically decided that soldiers would be authorized to exercise self-defense. This meant that soldiers who were in danger could legitimately fire their weapons to protect themselves “under the Garrison Decree and Article 123 of the Military Service Regulations.”

“Since the ‘Garrison Decree’ was limited to units that were permanently stationed somewhere, it couldn’t have applied to an airborne unit [that was operating on assignment in a particular area]. And since the Military Service Regulations concern the use of weapons by soldiers on guard duty, the soldiers in the airborne unit that fired the volley can’t be regarded as having been exercising their authority as guards,” said Lee Jae-ui, a scholar who researches the Gwangju Democratization Movement.

Nobody charged with murder of civilians

Five civilians were killed in the first volley of gunfire at Gwangju Station on the evening of May 20, but nobody was charged with committing homicide during an insurrection in connection with their deaths. While 36 people were killed during another volley by government troops in front of the South Jeolla Provincial Office the next day, on May 21, the investigators concluded that they were just victims of the riots that had occurred following the coup and during the Gwangju movement and failed to determine who had given the order to fire.

The only victims submitted by the prosecutors and accepted by the court as evidence of committing homicide during an insurrection (one of the charges facing Chun Doo-hwan, Lee Hui-seong, Ju Yeong-bok, Hwang Yeong-si, and Jeong Ho-yong) were the 18 people who were fatally shot while the government troops were taking over the South Jeolla Provincial Office. (That was the Sangmu Chungjeong operation, which ran from the night of May 26 to the early hours of May 27.)

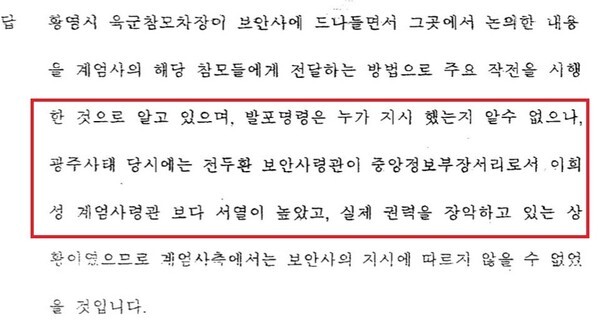

Determining who gave the order to fire during the Gwangju movement is also linked to the dual command structure that was in place. In addition to the official chain of command in the military, the airborne brigade was also reporting to the Special Forces Command, which itself reported to the Defense Security Command. It was this alternate chain of command that likely gave operational instructions, including the order to fire.

That’s the implication of what Kim Byeong-du, head of the DSC branch at the Army Headquarters, told the prosecutors during their investigation. “It’s impossible to know who gave the order to fire. That said, Chun Doo-hwan then defense security commander and acting director of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency at the time of the Gwangju movement, giving him a higher rank than Martial Law Commander Lee Hui-seong; Chun was also the de facto ruler of the country. Under those circumstances, the Martial Law Command would have had to follow the instructions of the Defense Security Command,” Kim said.

The problem is that too many years have passed, which is made clear by the account of a former high-ranking prosecutor who was involved in the 1995 investigation. “We brought all of the main people involved except for the ringleaders [Chun Doo-hwan and Roh Tae-woo] to Olympia Hotel in Seoul’s Pyeongchang neighborhood and questioned them one by one. When we compared their statements later, we found they were all inconsistent on key points. The 15 years that had passed since the events concerned had corrupted their memories, which made the investigation extremely difficult,” the prosecutor said.

The span of time that has elapsed is now nearly three times as long, implying that any investigation will be all the more challenging. It remains to be seen whether the government commission investigating the Gwangju movement, which began its work on May 12, will be able to achieve results despite all the time that has elapsed.

By Jung Dae-ha, Gwangju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0517/8117159322045222.jpg) [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later

[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later![[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0516/7417158465908824.jpg) [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence- [Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation

- [Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- [Column] How to win back readers who’ve turned to YouTube for news

- [Column] Welcome to the president’s pity party

- [Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

- [Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- [Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

Most viewed articles

- 1[Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- 2[Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- 3[Exclusive] Unearthed memo suggests Gwangju Uprising missing may have been cremated

- 4Xi, Putin ‘oppose acts of military intimidation’ against N. Korea by US in joint statement

- 5‘Shot, stabbed, piled on a truck’: Mystery of missing dead at Gwangju Prison

- 6[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

- 7Spotlight turns to Hyundai Group Chairwoman’s visit to North Korea

- 8[Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

- 9[Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- 10[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner t