hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Gwangju residents debate whether to preserve or destroy monuments to Chun Doo-hwan

Which takes precedence—conservation or retribution? Monuments to former South Korean president Chun Doo-hwan that are still standing in the old cemetery for the Gwangju Democratization Movement and other sites in the city have become the center of controversy.

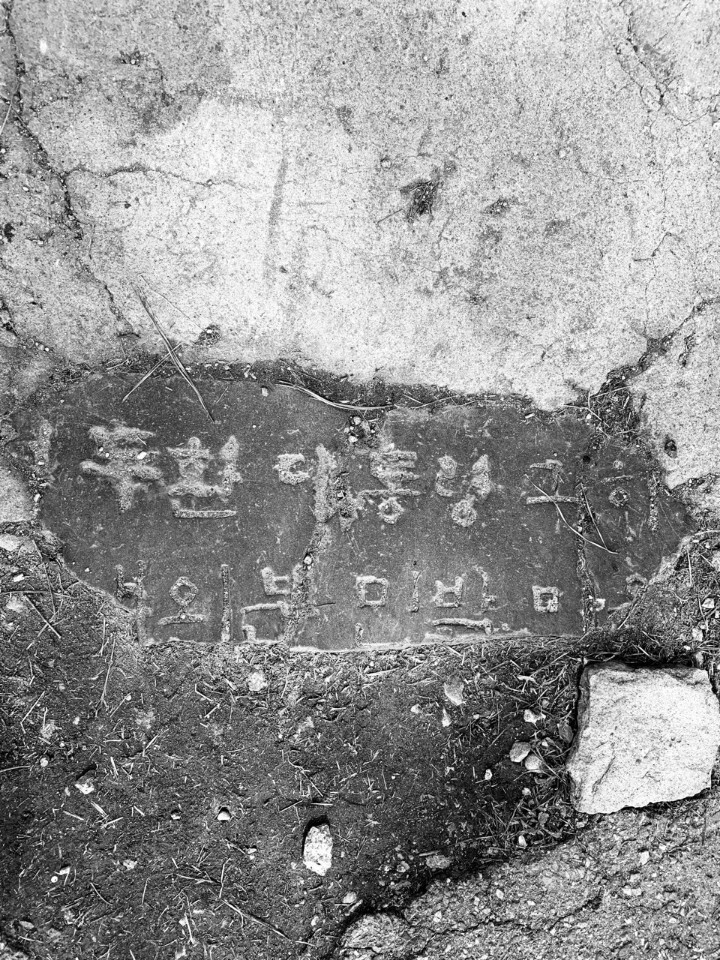

A stone memorial to Chun is buried in the ground at the entrance to the old cemetery for victims of the movement in the Mangwol neighborhood of Gwangju’s Buk District. The memorial was built after Chun and his wife had to spend the night in Seongsan Village, Goseo Township, Damyang County, South Jeolla Province, after being unable to stay in Gwangju during a visit to the city on Mar. 10, 1982.

In January 1989, a group called the Society of Friends of Democracy in Gwangju and South Jeolla crushed the memorial and buried it at the entrance to the cemetery where those massacred during the uprising had once lay at rest. A notice board asks visitors to “tread on the memorial to comfort the vengeful spirits” of those killed in the massacre. Even after the May 18th National Cemetery was built in 1997, visitors to the old cemetery, the original burial place of those who laid down their lives for the cause of democracy, have trodden on the memorial.

The rapid effacement of the memorial by visitors to the old cemetery has led to cautious calls for its conservation.

“Despite the narrative of Chun’s memorial being moved, smashed, and buried, [the memorial] itself has historical value. If we leave things as they are, the memorial is in danger of disappearing altogether,” said Im Ui-jin, a pastor who is also known as a poet and a painter.

But one of the former members of the civilian militia that fought in the uprising didn’t agree. “Stepping on the memorial in retribution is historical education, too.”

There are also conflicting views about how to deal with the 11th Special Forces Airborne Brigade’s memorial to Chun Doo-hwan, which was moved to the May 18 Freedom Park, in the Chipyeong neighborhood of Gwangju’s Seo District. This memorial was erected in 1983, when the 11th Special Forces Airborne Brigade, which had taken part in the forceful suppression of the uprising, moved its base from Hwacheon County, Gangwon Province, to Damyang County, South Jeolla Province. The memorial praises Chun for “being in the vanguard of the advancement of the fatherland.”

This memorial was moved to May 18 Freedom Park after it was ownership was transferred to the city of Gwangju on May 16. On June 3, organizations representing those who were injured and detained and those who lost loved ones during the Gwangju Democratization Movement temporarily shelved a plan to bury the memorial at the entrance of the park so that it would be trodden on by passing visitors.

But just as with the memorial at the old cemetery, there is disagreement about whether the airborne brigade’s memorial should be buried. If the memorial stones to Chun are damaged, some say, it could complicate Gwangju’s efforts to recover other objects symbolically connected to the movement. The base of the 11th Special Forces Airborne Brigade contains a memorial tower honoring the spirits of government troops who died while suppressing the movement, and other memorials to Chun are reportedly in the possession of the 3rd and 7th Airborne Brigades, the 20th Division, and the 31st Division. The city is also in consultation with the Jogye Order of Buddhism about recovering a bell inscribed with Chun’s name at Mugak Temple, at the Sangmudae military base in Jangseong, South Jeolla Province, but little progress has reportedly been made in that regard.

“Rather than burying the memorial stones, we need to bring together five or six memorials related to Chun, including the Buddhist bell inscribed with his name, in one place where they can be preserved and used for the educational purpose of teaching the lessons of history,” said Kim Hu-sik, head of a group for those injured in the Gwangju Democratization Movement. While Kim understands the anger against Chun, who has misrepresented the facts of the uprising and disparaged its victims, he emphasizes that these memorials are themselves historical artifacts.

“The old stockade at the Sangmudae base where the people arrested by the martial law troops were taken on May 27, 1980, is a very important historical site in relation to the Gwangju Democratization Movement. Burying the memorials and stepping on them to signify our contempt and vengeance for Chun is a more meaningful form of historical education,” said Yang Gi-nam, who was a member of the civilian militia’s strike force during the movement.

Another victim of the movement put it more bluntly: “It’s absurd to preserve memorials that were built to praise Chun for the way he suppressed the Gwangju Democratization Movement.”

By Jung Dae-ha, Gwangju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 3S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 4Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 5Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 6[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 7OECD upgrades Korea’s growth forecast from 2.2% to 2.6%

- 8Inside the law for a special counsel probe over a Korean Marine’s death

- 9Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 10[Exclusive] Hanshin University deported 22 Uzbeks in manner that felt like abduction, students say