hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

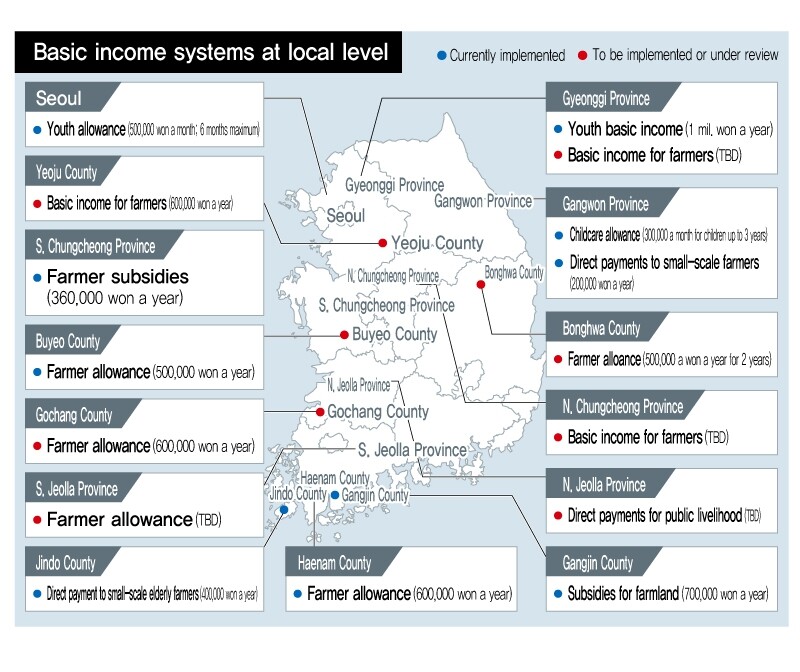

Local governments introduce basic income experiments

“It feels like waiting for the harvest after a year of farming.”

Jeong Geo-seop grinned as he spoke on Apr. 29 about his upcoming request for a “farmer’s allowance,” which was set to go into effect three days later. The 54-year-old farmer is one of many in Haenam County, South Jeolla Province, who have dedicated themselves to convincing the county government to institute a farmer’s allowance ordinance since the local election on June 13 of last year. Thanks to their efforts, the county will be paying an annual allowance of 600,000 won ($US515.45) per farm to 15,000 households as of this May. It’s the first such program anywhere in South Korea. To be sure, the farmers know that 50,000 won (US$42.94) a month won’t mean any major changes for their livelihoods – but the allowance holds special meaning to them.

“I don’t really expect to see our incomes or livelihoods improve with the farmer’s allowance, but I think it could instill a sense of pride in farmers as producers of food, since it’s a matter of society incentivizing the public service aspect of agriculture and farming communities,” Jeong said.

“It’s meaningful in terms of the public recognizing the value of farmers,” he added.

Basic income policies are being increasingly adopted throughout South Korea. The local government basic income experiments ushered in with the respective adoption of “youth dividends” and “youth allowances” by Seongnam and Seoul in 2016 are evolving into different forms three years later.

In Gangwon Province, basic childcare allowances amounting to 300,000 won (US$257.66) a month for four years are being provided for every child born as of this year. It’s the first example yet of a childcare allowance paid out by a local government. Together with the child allowance (100,000 won, or US$85.88, per month) and family childcare allowance (100,000–200,000 won, or US$85.88-171.75, per month based on age) paid by the central government (Ministry of Health and Welfare), it means parents could receive up to 600,000 won (US$515.25) a month in allowances.

Gyeonggi Province also began implementation of its basic youth income (youth dividend) on Apr. 9. Residents at least 24 years of age who have resided in the province for at least three years are now entitled to 250,000 won (US$214.72) a quarter – 1,000,000 won (US$858.88) a year – in local currency regardless of income or profession. Goseong County, South Gyeongsang Province, pays youth allowances (“dream fares”) in the form of electronic vouchers worth 100,000 won (US$85.91) a month to young people aged 13 to 18, while Bucheon and Ansan in Gyeonggi Province are currently discussing the introduction of a basic income for artists.

Farmer’s allowances in particular have been introduced or are being considered in a growing number of regions. An Apr. 29 examination of figures from the Korean Peasants’ League and Park Gyeong-cheol, a senior research fellow at the Chungnam Institute, showed a total of 54 local governments had introduced or were pursuing farmer’s allowances. This included nine metropolitan/provincial local governments in places such as North and South Jeolla and Gangwon Provinces, along with 45 basic county governments such as Gangjin and Haenam in South Jeolla, Bonghwa in North Gyeongsang, and Buyeo in South Chungcheong. With the current farming subsidy system structured in a way that could potentially exacerbate inequalities and imbalances within farming communities – including payouts based on the area farmed, which translate into larger amounts for those with more land – many regions are weighing the payment of farmer’s allowances as a form of basic income.

“At a time when agriculture and farming communities are losing their foundation through indiscriminate free trade and when farmers are finding it hard to carry on, some are suggesting the need for a basic income or allowances for farmers,” Park Gyeong-cheol noted.

Thirty-five local governments around South Korea are also preparing to institute basic income systems. At the opening of the 2019 Republic of Korea Basic Income Exposition at Suwon Convention Center that day, Gyeonggi Governor Lee Jae-myung adopted a joint “basic income local government council” declaration alongside the heads of 30 local governments within the province, including Suwon Mayor Yeom Tae-young, and 35 other local government heads, including Baek Du-hyeon of Goseong County, Park Jeong-hyeon of Buyeo, and Deputy Governor Jeong To-jin of Gochang, North Jeolla. In the declaration, they pledged to “work to establish pan-national support for the adoption of basic incomes, enact framework laws for basic incomes, and establish the necessary financial resources for basic incomes.”

Controversy regarding payment to wealthy individuals

The problem is that the topic of basic income remains the subject of debate in South Korea. With payouts made regardless of the amount of an individual’s income or assets, the discussion has been constrained by questions about why even the wealthy should receive assistance.

In response, experts suggested the basic income issue should be approach from a perspective of rights for all South Koreans. Kang Nam-hoon, a professor of economics at Hanshin University and chairman of the Basic Income Korean Network, noted, “Many of the advanced economies are already paying out universal allowances such as student allowances.”

“If the concept behind a basic welfare system that involves selectively helping out only people who are poor is about guaranteeing a minimum livelihood at a low cost, then a basic income should be approached in terms of right for all citizens and equally sharing profits that come from shared social assets such as land and the environment,” he said.

Financial stumbling blocks

Financial resources have been another stumbling block. For Gyeonggi Province to expand the basic youth income into a basic income of 1,000,000 won (US$858) a year per resident would require a yearly budget of 13 trillion won (US$11.15 billion). The province’s budget for one year amounts to 20 trillion won (US$17.16 billion). This is why Governor Lee Jae-myung and basic income researchers in South Korea have been calling for the adoption of a basic income-oriented land ownership tax. Under a land ownership tax system, all landowners would be taxed according to their land area, with the revenues redistributed as a basic income.

“Achieving a basic income entails procuring funding from land and natural resources. It’s a just approach to providing financial means while mitigating real estate inequality,” said Nam Gi-eop, director of the Institute of Land and Liberty.

Some are arguing for a proactive role from the central government in expanding discussions on a basic income. Almaz Zelleke, a professor at New York University, attributed the growing interest in a basic income to its being the only answer to capitalism to resolve income inequality worldwide.

“A basic income is a matter of redistributing wealth and pursuing a way for everyone to prosper rather than a particular segment,” she explained.

“Expanding basic income will require wealth taxes and other means of redistributing wealth, which is ultimately possible through legislative changes by the central government.”

By Hong Yong-duk, South Gyeonggi correspondent, and Ahn Kwan-ok, Gwangju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 2No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 3‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 4Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 5Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 6Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 7Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 8[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 9[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 10[Editorial] In the year since the Sewol, our national community has drowned