hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

On the run and hiding in caves from punitive soldiers looking for blood

Word came that their father had been shot after being taken by the police. The two brothers heard the news while seeking refuge in the village of Hallim, leaving behind their home village of Geumak in the hills of northwest Jeju Island. He had been slain at a five-day traditional market site in Hallim.

“It’s all over now,” their mother said, sinking to the ground. Instead of Hallim, she took her sons to the home of relatives living in the nearby village of Myeongwol. The date was Nov. 20, 1948.

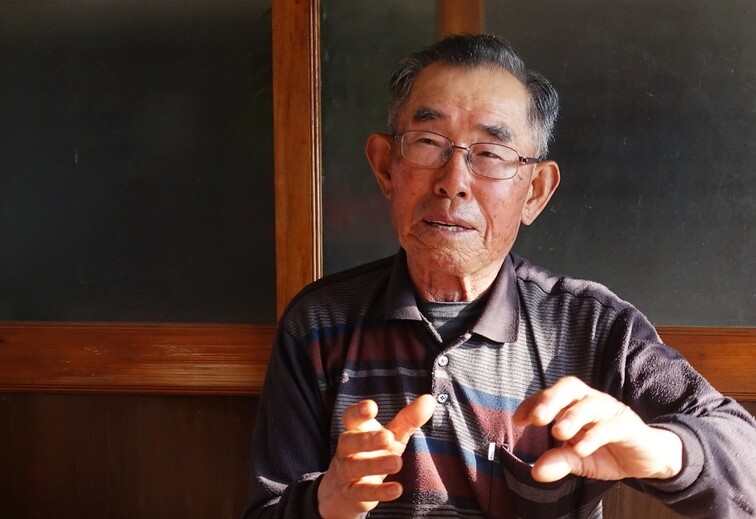

On that day, the anti-communist punitive forces ordered the village of Geumak to be evacuated. The village had suffered major damage in the events of the Jeju Uprising (known locally as Jeju April 3, or the Jeju Massacre). Eighty-seven years old today, Yang Seo-ok was then a 16-year-old sixth-year student at Geumak Elementary School. He left the village with his mother Kang Gi-in, then 48, who carried his five-year-old brother Chang-ok (now 76) on her back. His older brothers Bo-ok and Yun-ok, then 25 and 19, had already fled after coming onto the punitive forces’ radar.

If even one member of a family was found to be missing from the home, the punitive forces would kill the remaining family members as members of a “fugitive’s household.” Chang-ok’s wife Byeon Yeong-ja, now 77, recalled the message she heard from her mother-in-law.

“She said she had seen the writing on the wall the day before his father was taken. She also bought some meat for the children to eat,” she said.

The following day, the father left the home, saying that he would “have to die for the crime of having a intellectual child.” He was taken to Hallim by way of Jeoji Police Station; two days later, he was killed.

The following Jan. 9, the second brother Yun-ok turned up in the middle of the night in Myeongwol, where the family was taking refuge.

“You’ll all be killed if you stay here,” he told them. “If you want to survive, you’ll have to go into the hills.”

With Chang-ok on her back, the mother took a moment to pack up the dishes used for ancestral rites.

“She said she took them along so she could hold ancestral ceremonies while in hiding,” Byeon explained.

The family trudged through the snow, passing through the Jung and Gorim neighborhoods of Myeongwol Village. By the time they’d gotten as high as Geumak Village, it was dawn. In the confusion, with government troops on their trail, Chang-ok and Seo-ok had lost track of Yun-ok. The siblings learned what had happened to their oldest brother, Bo-ok, from the Geumak villagers. On Dec. 8, 1948, 28 days after their father had died, Bo-ok had been shot and killed by government troops in the village. Bo-ok was an intellectual, having returned home two years before Korea’s liberation from Japan after traveling to Japan with his father in the mid-1930s and attending university there for two years.

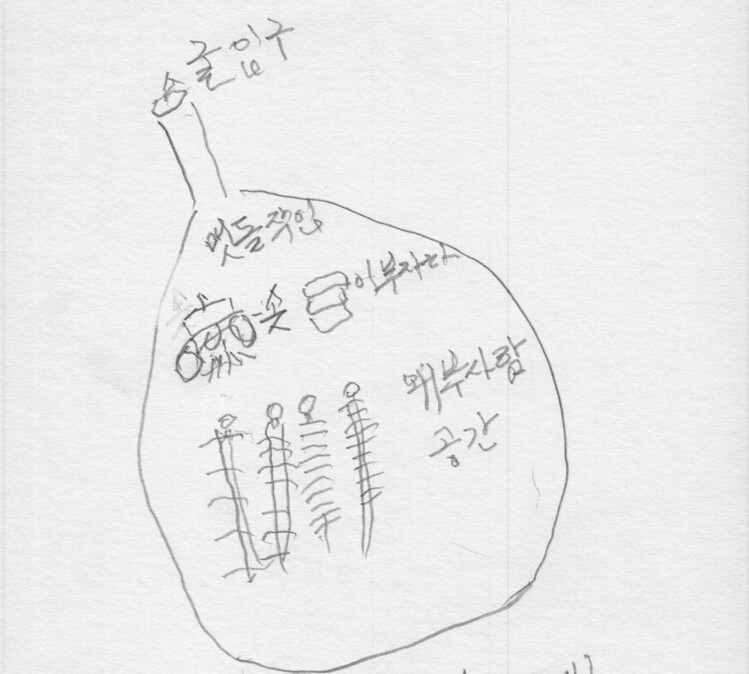

Hearing that government troops were approaching, the villagers passed over a parasitic volcano called Geum Oreum and hid in the woods. A thick blanket of snow covered the ground, coming up to Seo-ok’s waist. While they were struggling through the snow, they came upon a woman carrying a baby, who told them that the only way to survive was to flee in the direction she was pointing. Seo-ok threw himself down on the ground to help his mother and little brother make their way through the snow. When they reached the ridge of Noro Oreum (at an elevation of 1,070m), in the upland region of Yusuam Village, Aewol Township, the moon rose above the white-topped ridges of Mt. Halla, shining brightly. After passing Saebyeol Oreum (519m), they found a cave where the family of the woman they’d met earlier was hiding, in the vicinity of Nuun Oreum (407m), just over 3km away from Geumak Village. The boys’ mother, Gi-in, held Chang-ok to her dry breast to keep him from wailing, afraid that someone outside the cave would hear him.

A few days later, Seo-ok was spotted by government troops while he was exploring the area around the top of Nuun Oreum. He ran down the hill, followed by the troops, who soon found the cave where his mother and little brother were holed up. “The soldiers fired their guns in front of the cave and threatened to shoot us if we didn’t come out [of the cave]. When Mom went out, a soldier hit her on the head with the stock of his rifle. They tied up Mom and the other woman with ropes to keep them from running away and forced them to walk barefoot all the way to the Hallim police branch, which was more than 10km away. At the police branch, Chang-ok, who was on his mother’s back, cried out from fear, prompting a policeman to yank on his left foot, leaving a lasting limp. To this day, Chang-ok has to wear a bandage on his foot. Chang-ok and Gi-in were taken to police branches in Moseulpo and then Seogwipo, where they boarded a ship. After arriving in Sanji Harbor, in Jeju Township, they were detained at a distillery. This all transpired in late February and early March 1949.

After being separated from his mother, Seo-ok managed to survive in the hills for about two months, despite the winter chill. “The cold wasn’t the problem. Since it was a matter of life and death, I only thought about getting away,” Seo-ok said. Late that March, he was finally caught by soldiers from the 2nd Regiment and sent to Wondong village and then on to the Jeju distillery for detention. When Seo-ok was out in the yard at the distillery one day, he ran into his older brother Yun-ok. But Yun-ok warned Seo-ok not to get too close. Pointing to their mother, he said Seo-ok was young enough to survive if he stayed with her. Seo-ok had to swallow his joy at seeing his older brother, and that reunion proved to be their final meeting. Yun-ok was tried in a military tribunal that July and transferred to a prison in Daejeon. After the outbreak of the Korean War, he went missing. His gravestone is among those erected for those who went missing at the Jeju April 3 Peace Park.

On Apr. 9, 1949, President Rhee Syngman paid a visit to the distillery on his first trip to Jeju Island. In a speech to some 2,800 islanders who were being held at the camp, Rhee said, “The past is the past. Live your lives as loyal citizens of the Republic of Korea.” That was after he’d already had the island ruthlessly pacified. Seo-ok said he heard the president say over the loudspeaker that everyone at the camp would be cleared of charges except for those between the ages of 16 and 44. At the end of that month, Seo-ok, Chang-ok and Gi-in were sent to the Hallim police branch and then released.

After five years of communal life in Hallim Village and the Gorim neighborhood, the family returned to Geumak Village, which had been rebuilt. For the two brothers, the Jeju Massacre remained a lifelong trauma. “Even after we got married, hearing someone say, ‘You got caught up in ideology’ was enough to make Chang-ok weep when he got home. Whenever he drank, he’d get teary-eyed and talk about the massacre” said Chang-ok’s wife, surnamed Byeon. Chang-ok is an active member of the Association for Disabilities Caused by the Jeju Massacre. Though Seo-ok rarely talks about the Jeju Massacre, he did mention that he’d gone to the Jeju April 3 Peace Park for the memorial service last year because he wanted to hear President Moon’s speech. “None of us could survive if we faced another disaster like that,” he said. For these two brothers, the Jeju Massacre is still an unfinished story.

By Huh Ho-joon, Jeju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 2Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 3[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 4No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 5[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 6[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 7Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 8Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 9Marriages nosedived 40% over last 10 years in Korea, a factor in low birth rate

- 101 in 5 unwed Korean women want child-free life, study shows