hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Interview] Near the end of his life, a former POW seeks a simple return home

“The sea breathed, a heavy flop of blue, bulky scales deeper than crayon. The Tagore, an Indian boat carrying freed prisoners to a neutral land, shook its three thousand-ton body neatly painted in white, sliding through South China Sea air packed thickly like a mass of objects.”

“The Square,” a 1960 novel by Choi In-hun, begins with the image of a boat leaving Incheon Harbor for neutral India after the end of the Korean War. On board is protagonist Lee Myeong-jun, one of many prisoners from the conflict who opted for a third country instead of repatriation.

The situation in February 1954 was much like that described in the book. The British transport Asturias really did leave for India from Incheon carrying 77 released Korean POWs (88 including Chinese POWs) who had chosen a third country. Fifty-five of them went on to Brazil, nine to Argentina. One of the former was Kim Myeong-bok, now 80.

Recently, Kim returned to South Korean soil for the first time in the 65 years since he left his home of Ryongchon, North Pyongan Province (now in North Korea) and 61 years since he arrived in Brazil by way of India.

“I was 15 years old and studying in the summer when the soldiers burst in and told everyone to get into the truck. We’d been drafted as new recruits in the People’s Army. Who could have known it would take this long to return?”

Kim’s eyes looked heavenward as he retrieved the ancient memories on Aug. 10. Fighting in the Korean War changed literally everything for him. Less than a month after he joined, he had been taken prisoner. For three years, he was shifted between camps from Busan to Geoje, Yeongcheon, Masan, and the neutral zone (Panmunjeom). Then armistice came.

The question was one he had likely heard - and asked himself - over the decades. Couldn’t he have returned to his home in North Korea, or stayed in the South? After a bit of hemming and hawing, he finally shared the story of what he experience in the Panmunjeom camp.

“One of my mates who was in my tent was caught talking in his sleep about how he wanted to go home, and he was beaten to death,” Kim said. “In the middle of the night, when no one could find about it. It was between North Korea, where simply being taken prisoner was seen as a crime, and South Korea, where they beat you to death for saying you wanted to go home. I couldn’t make that choice.”

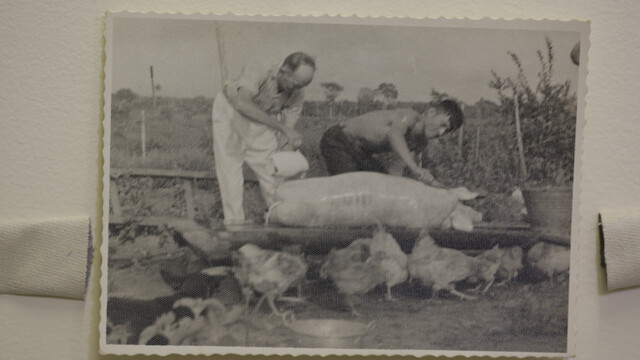

In 1956, Kim settled in Cuiaba, a city in the hinterlands of Mato Grosso over 1,000 km from Sao Paulo. Life was hard for someone didn’t speak the language, but he finally met and married a kind Brazilian woman, fathering two sons and two daughters. He also put his children through university with money he earned farming.

“I was so busy surviving that I could only miss my home in North Korea. They say even tigers seek their home when they die. . . . My parents must have passed away already. I had a five-year-old sister and a two-year-old little brother - maybe they’re still alive now? Is Bupyong Church still around where I used to go every Sunday? I’d just like to set foot on the ground there.”

Kim started to cry and had difficulty containing his sobs. He spoke with a strained voice, the result of an airway injury he suffered during intubation after catching dengue fever five years ago.

“I’m sorry. I’ve gotten so old. I’m sorry.”

Kim arrived for his visit bearing the remains of Kim Seo-guk and Kim Chang-eon, two colleagues who died in Brazil. Their family members had asked him to honor their wish to go home somehow, even if they passed away first.

But the path to his actual home remains in doubt. So far he has appealed not only to the North Korean embassy in Brazil and the Brazilian embassy in North Korea, but also to the South Korean government. The response has been uniformly lukewarm.

“There isn’t any time left. I‘ll be ninety before long, and I could die any day. All I can do is hope for a miracle. . . .”

The one bit of consolation for him is the fact that a movie is now being made about the story of surviving POWs like him. The documentary, called “Return Home,” is by director Cho Kyeong-duk. Cho first learned about the surviving POWs while visiting Brazil for the Sao Paulo Film Festival, where his “Sex Volunteer,” a 2009 documentary about the sexual rights of the severely disabled, took top honors. The movie has been in the making for more than five years now.

Kim and Cho left Brazil in May, traveling to India and Argentina before arriving in South Korea in late July.

“As I traveled to Busan, Geoje, Yangpyeong, and other places where I’d been a prisoner, I found myself remembering a lot of Korean, and my desire to go home grew even stronger,” said Kim.

“I’m going to Panmunjeom on Aug. 13,” he added. “Maybe I’ll be able to see my home all the way from there?”

By Yoo Seon-hee, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 4Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 546% of cases of violence against women in Korea perpetrated by intimate partner, study finds

- 6Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 7[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 8[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 9Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 10“Parental care contracts” increasingly common in South Korea