hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[In depth] The extent of Japan’s coercion in the mobilization of comfort women

By Gil Yun-hyung, Tokyo correspondent

The scene: meeting room #1, hall #2, in the House of Representatives in the Chiyoda Ward of Tokyo, Japan on Oct. 17. “How do you think the Sankei Shimbun was able to get a hold of the documents that the government had refused to give to us when we asked for them?” the lecturer asked. “I think that someone in the Abe administration [which is trying to undermine the Kono Statement] must have deliberately leaked the documents to the paper.”

Hisatomo Kobayashi, secretary general of the Network for Uncovering the Truth about Forced Labor, was giving a lecture to a meeting of the Alliance for Resolving the Issue of the Comfort Women Together. The alliance was voluntarily created by Japanese citizens who hope to find a solution to this issue.

The topic of Kobayashi’s lecture was the forcible mobilization of the comfort women as illustrated through Japanese laws and military regulations that were in place at the time that the comfort women were mobilized.

The issue of the comfort women is at the frontline of ongoing efforts in Japanese society to rewrite history. Since Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe suffered severe criticism for his remarks in April that there is no set definition for what constitutes a war of aggression, he put some distance between himself and historical issues and has concentrated, at least outwardly, on economic issues.

Nevertheless, a heated battle continues in the Japanese press. In September alone, a number of articles appeared on the issue. Kyodo News ran a story on Sept. 6 claiming that the Japanese army forced Dutch women imprisoned at a POW camp in Indonesia to serve as comfort women.

On Sept. 13 and 14, the Asahi Shimbun published a scoop contending that the Japanese government applied various kinds of pressure to the Indonesian government to prevent the issue of the comfort women from becoming an international issue around the time of the Kono Statement was made public.

The Sankei Shimbun, one of Japan’s leading conservative newspapers, mounted a counterattack in its Sept. 16 issue. Having acquired the transcripts of interviews with 16 Korean comfort women, which had been the basis for drafting the Kono Statement, the paper pointed out problems with these interviews. The article argued that since the credibility of the testimony of the comfort women is doubtful, the Kono Statement ought to be revised.

While there are a variety of controversial aspects related to the issue of the comfort women, ultimately, the crux of the matter is the forcible nature of the comfort women’s mobilization and how one views the attitude adopted by the Kono Statement. This explains why Kyodo News covered the case of the Indonesian POW camp, which constitutes direct evidence that the Japanese government forced women to serve as sex slaves. It also explains why the Sankei Shimbun picked holes in the testimony of the elderly Korean women as part of its efforts to revise the Kono Statement.

But how did the mobilization actually happen?To be sure, there are mythical elements to Korean society’s understanding of the comfort women.

Japanese researchers and activists who have long worked to publicize and resolve the issue of the comfort women suggest that a failure to distinguish the comfort women from Korean women drafted to work at factories was partly to blame for creating a myth of victimization.

The factory women that the authorities in the colonial administration of Korea drafted in accordance with associated laws after Japan instituted the “total mobilization of the nation” system in 1938 were presumed to be comfort women,. This standard was then used as the basis for calculating the number of victims and the extent of damage they suffered.

It is commonly thought in Korea that the Japanese colonial administration ordered the kidnapping of girls between the ages of 12 to 14 and forced them into sexual servitude at the comfort women stations. However, according to the evidence that has been uncovered so far, that kind of compulsion either did not occur at all or occurred with extreme rarity.

But if that is the case, why did the Japanese government acknowledge in the Kono Statement that the Japanese military was directly involved in coercion? The reason is that the government was forced to reach that conclusion after a comprehensive review of records from the time and the testimony of the victims.

According to a book written by Toshio Hanabusa, a longtime research of Korea-Japan historical issues, Article 226 of the Japanese criminal code at the time prohibited kidnapping people and taking them overseas, with a penalty of a minimum two years imprisonment. There was also a special act forbidding prostitution overseas, which made it illegal for Japanese women to be sent overseas to take part in prostitution.

Hanabusa, who is head of the Korea-Japan Joint Action to Resolve the Issue of the Japanese Military Comfort Women, wrote “How Should We View Government and Military Coercion of the Comfort Women?”

In fact, the Japanese Supreme Court found someone guilty of such a crime in March 1937. The convicted man was a broker who had tricked a woman from Nagasaki into going to a navy comfort station in Shanghai, China. This implies that Japanese society at the time regarded it a crime to deceive women into going overseas and then force them into prostitution.

However, the situation changed rapidly after the beginning of the Sino-Japanese War in July 1937. The Japanese army revised the regulations concerning military canteens in Sept. 1937, making it possible to set up military comfort stations.

Article 3 of the updated regulation stated that “a comfort station can be established in a unit with more than 500 people, and the person responsible for maintenance is the unit commander, the person who sets up the station.”

Article 6 said that “the station will be managed by a contractor who receives a permit from the unit commander, and the contractor will be treated as a civilian working for the military and will wear a certain uniform.”

In consequence, the Central China Area Army command, which included Shanghai and Nanjing, decided to set up comfort stations in Dec. 1937. The civilian contractors to whom the military entrusted the job got to work and began recruiting large numbers of women.

As a result, the Japanese police found themselves in a serious quandary. They found that the contractors hired by the Japanese military were in fact committing crimes.

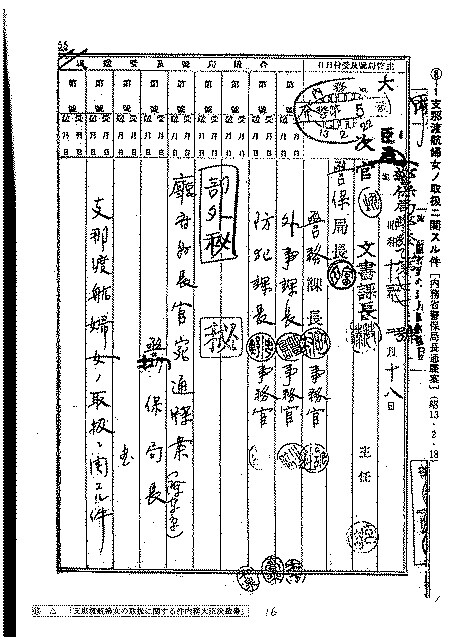

Following repeated inquiries from police departments in various prefectures, the Ministry of Interior asked the police for their cooperation in Feb. 1938. The ministry sent out an internal order titled, “Regarding the Treatment of Women Traveling to China,” in which it said, “it is necessary to consider measures that are appropriate for the situation.”

In the same document, the Ministry established criteria for issuing a travel permit: women had to be prostitutes in Japan who were over 21 years of age and who did not have any sexually transmitted diseases. Furthermore, they had to have the consent of their parents and had to go in person to a police station to request the travel permit.

Furthermore, the Ministry stated that the permit would only be given on the condition that the women would be brought back to Japan at the completion of their two-year contract of service.

The interesting thing here is that this notice was only distributed inside Japan. Hanabusa explains that the reason for this was that when Japan ratified the international convention about the prostitution of women, it had inserted a provision that excluded its colonies.

But after the hiring of those women actually began, the Ministry’s regulations were not adhered to very faithfully inside Japan, either. As a result, it is not difficult to infer what kind of things would have happened in the Japanese colony of Korea, where this notice was not distributed at all.

In their testimony, a large number of Korean comfort women explained that they had been deceived by promises that they would be given a good job when they were in their mid-to-late teens and found themselves coerced into working as comfort women.

Since such acts of kidnapping, which amount to human trafficking, occurred throughout Korea, it is inconceivable that they were not detected by the Japanese colonial police. The fact that no efforts were made to curtail this behavior despite an awareness of the fact that such acts were taking place constitutes aiding and abetting of the crime.

Trafficking by private contractors with police acquiescenceIn the end, no Japanese deny the existence of the comfort women system itself. Rather, there are differences of opinion about the extent of the Japanese government’s complicity in forcing women to become comfort women.

Taking into consideration all of these facts along with the testimony of the victims, the Kono Statement acknowledged that, while the parties who were recruiting the comfort women were private contractors, there were many examples of women being recruited against their will. The statement also accepted the testimony of former comfort women, admitting that there were exceptional cases in which government authorities were also involved. This can be understood as coercion of comfort women, comfort being defined in the loose sense of the word.

In March 2007, during his first term as Japanese prime minister, Abe tried to use a cabinet decision to revise the Kono Statement to say that no evidence had been found among the documents possessed by the Japanese government of Japanese government officials giving direct orders for women to be coerced into service as comfort women. Obviously, this was a pathetic move aimed at evading as much of the responsibility as possible.

But while this was a denial of the legal responsibility that would come from government coercion in the narrow sense of the word, it was not an attempt to deny the comfort woman system in its entirety.

Acknowledging government coercion in mobilizing the comfort women in the broad sense of the world also poses a philosophical challenge to Korean society. There was a time when the Korean government assembled female sex workers in US military camptowns, conducted STD tests every other week, and constantly reinforced the idea that they were being patriotic by earning dollars, even though prostitution was technically illegal in the country.

As a society, Koreans need to give some serious thought to how much attention has been paid to the human rights concerns of the women who worked in these camptowns. They are no different from the comfort women in terms of the government’s negligence, complicity, and facilitation.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 2[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 3‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 4Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 5The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 6Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 7Up-and-coming Indonesian group StarBe spills what it learned during K-pop training in Seoul

- 8[Column] Action on climate change isn’t driving inflation – fossil fuels are

- 9[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 10Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February