hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Chaebol getting plumper, as so-called trickle-down effect wanes

As time goes by, the profitability (added value) of South Korea’s four biggest chaebol groups - including Samsung and Hyundai Motor - is coming to account for an increasingly larger share of the South Korean economy. But while wealth is concentrating in these four chaebol, other groups’ share of profitability is declining, suggesting that polarization in South Korean society is even spreading to its chaebol.

Furthermore, South Korea’s biggest chaebol are more likely to distribute their added value to stockholders or to hold it as cash reserves, paying out a smaller share in wages to employees, the primary source of household income. This represents a weakening of the so-called trickle-down effect, referring to the economic theory stating that strong corporate performance has a positive effect on the economy as a whole.

These arguments were contained in a report that the Economic Reform Research Institute (ERRI) published on Jan. 27. Titled “An Analysis of the Creation and Distribution of Added Value at the Top 50 Corporations,” the report was written by Kim Sang-jo, director of the institute.

The report analyzes the creation and distribution of added value between 2002 and 2013 at South Korea’s top 50 companies, ranked by added value.

Previous analyses of the wealth of South Korea’s chaebol have focused on their assets and revenue; this is the first to be based on added value.

Added value is the surplus created by the company itself, subtracting the raw materials and the parts made by subcontractors from the production output. The advantage of added value for researchers is that it can be used to analyze how companies create employment and income and distribute wages, interest, and dividends.

In 2013, added value created at Samsung Electronics, Hyundai Motor, and the rest of South Korea’s top 50 companies (excluding six companies for which financial figures were unavailable during the period of analysis) totaled 154.4 trillion won (US$143.24 billion), a 120% increase from 2002 (71.2 trillion won, or US$66.06 billion).

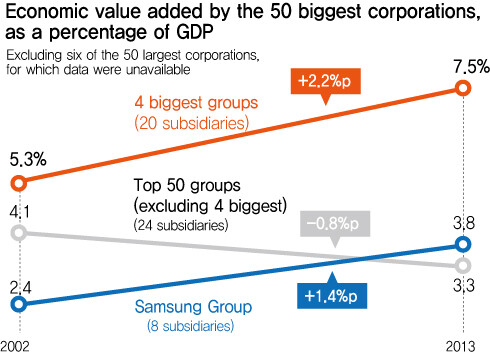

The percentage of South Korea’s nominal gross domestic product (GDP) represented by the top 50 companies climbed from 9.35% in 2002 to 10.81% in 2013, illustrating the concentration of wealth in the country.

But when companies in the group of 50 are individually examined, it becomes clear that, aside from the companies at the top, the rest are facing serious challenges.

Eight of the 50 companies in the study are subsidiaries of Samsung Group - the unrivaled behemoth of the South Korean economy - and their share of nominal GDP soared during the same period from 2.4% to 3.77%. The share of the 20 subsidiaries of South Korea‘s top four groups (Samsung, Hyundai Motor, SK, and LG) also rose from 5.3% to 7.53%.

Meanwhile, the other 24 large corporations’ share of nominal GDP fell from 4.05% to 3.27%.

“Aside from the four big groups, performance at South Korea‘s flagship companies is stagnant or in decline. Recently, Samsung and Hyundai Motor have seen sluggish performance as well, which is worrisome for the future of the South Korean economy. The government should consider narrowing the target of its current regulations on chaebol from companies with more than 5 trillion won (US$4.64 billion) in assets to the four big groups,” Kim said.

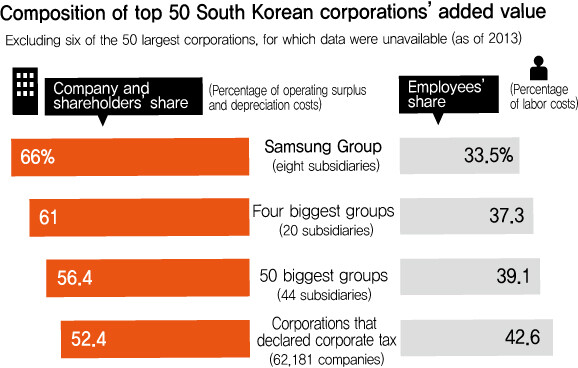

In addition, the proportion of added value at these 50 companies that reverts to the company and its stockholders in the form of operating surplus and the depreciation cost was 56.4% in 2013. This was higher than the proportion of added value that is paid to employees as wages, which was only 39.1%.

This trend was even more pronounced at the companies that ranked highest on the list, with operating surplus and depreciation cost accounting for 61.03% of added value at subsidiaries of South Korea’s four big groups. This percentage was even higher at subsidiaries of Samsung, where it was 66.03%.

At the same time, wages only accounted for 37.31% of added value at the subsidiaries of the four biggest chaebol, which was lower than the average across the 50 groups in the study. The percentage at subsidiaries of Samsung was even lower, at 33.45%.

The weakening of the trickle-down effect at South Korea’s top companies is also confirmed in the wage share (the ratio of labor cost to added value minus the depreciation cost).

The wage share at South Korea’s top 50 companies was 53.1% in 2013, lower than the rate of 55.1% at all of South Korea‘s large companies (62,181 companies, based on corporate tax returns).

The wage share was lower (49.2%) at subsidiaries of the four big groups, and lowest of all (42.1%) at subsidiaries of the Samsung Group.

South Korea’s top 50 companies are stingy about paying dividends to their stockholders, keeping the majority of operating surplus in the company coffers. 2013, the cash reserve ratio (based on the amount of earnings that can be retained) at these companies was 88.8%.

On the other hand, the payout ratio (the ratio of dividends to net income) was 25.7%, while the dividend rate (based on the nominal value of dividends) was just 2.1%.

“The majority of operating surplus and depreciation cost are reserved in the company, leaving a small share for wages, which is the primary source of household income. Even if South Korea‘s flagship companies continue to prosper, this will do very little to improve employment and wages for most Koreans,” Kim said.

The administration of South Korean President Park Geun-hye added “corporate income redistribution” to the tax code to encourage companies to invest, pay dividends, or raise wages when their profits exceed a certain level. But the waning trickle-down effect suggests that there is a high likelihood that this policy will fail, the report suggests.

“The amount of investment at the top 50 companies has been on the decline since 2010, with companies investing less than half of the funds available to them,” Kim said in a negative assessment of the government’s strategy for economic growth that involves easing regulations and reforming the labor market to promote investment.

While the government‘s policy of corporate income recirculation is aimed at reducing the wage gap and redistributing income, it is actually having the opposite effect, the report claims. Most of the benefits of the rising wages and increasing dividends resulting from the policy are accruing to regular workers at large corporations and financial asset managers.

“The government needs to consider aggressively offering tax breaks on expenditures that contribute to the improvement of the working conditions of employees and the management of small and medium-sized subcontractors. It also needs to increase the corporate tax rate, which would enable it to increase expenditures on social welfare, raise the minimum wage, and directly invest in aggressive labor market policies,” Kim said.

By Kwak Jung-soo, business correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 4Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 5[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 6Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 7[Reportage] On US campuses, student risk arrest as they call for divestment from Israel

- 8Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 9Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 10Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?