hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Late-generation scions running Korea’s chaebol may have charisma, but are they fit to lead?

Tesla CEO Elon Musk is a highly divisive individual. Those who adore him call him the real-life Tony Stark of the “Iron Man” comics, considering him to be a superhero who not only advances technology, but will one day save the world. Those who despise him scorn him as a selfish, rude narcissist.

In politics and psychology, charisma is explained as the ability to attract and charm others. If we were to summarize the results of research on charismatic business bigwigs, we could say that people admire charismatic CEOs, but such CEOs have a surprisingly large amount of faults.

Seeing as charismatic chaebol leaders have significant clout in the Korean business world and the economy in general, we need to have a thorough discussion of how we should deal with such individuals.

An aura reserved for the chosen few?

Whether we like it or not, chaebol conglomerates dominate the South Korean economy, and chairpersons control those companies. Currently, the third- and fourth-generation scions of the founding families sit at the head of the boardroom table for many of these firms.

These younger generations certainly weren’t the ones who built the company up from nothing, they lack entrepreneurial spirit, and don’t have much to show in terms of experience. Even their highly coveted roles atop the corporate ladder weren’t the product of fierce competition in which they proved themselves worthy. But even if we set aside an argument that the evaluation process should be stricter, we have to admit that there must be something more substantial to justify their power succession.

This is where charisma comes in, as absurd as it may sound. Let’s think about the time President Yoon Suk-yeol noshed on tteokbokki in Busan with the heads of various chaebol groups.

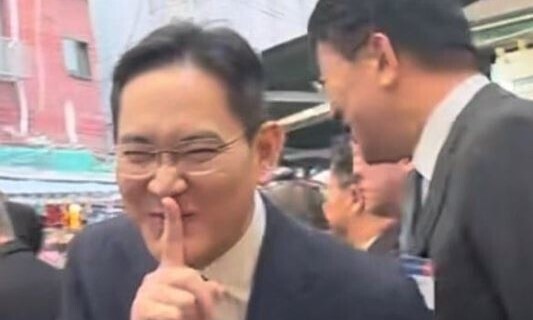

While Yoon almost immediately came under fire for using the busy chairpersons for a political stunt, a split-second image of Lee Jae-yong of Samsung impishly shushing the camera quickly became a viral meme, blowing up the Internet. A sign was put up in front of the fish cake stall he had visited marking “where Chairperson Lee stood.”

As trivial as this episode may seem, we can see the public’s perception of Lee as someone with charisma that sets him apart from others. People working at Samsung frequently comment on their chairperson’s “aura,” even if they have differing opinions on other matters.

In other words, company insiders believe that charisma is part of what justifies and legitimizes the succession of third- and fourth-generation offspring of founding families.

Do such charismatic CEOs improve corporate performance? While many may believe that the answer is a wholehearted yes, the results of various studies show that it is difficult to draw a definitive conclusion.

While there are various analyses, one significant interpretation suggests that the type of charisma influences the likelihood of improved corporate performance.

Charisma that is based on objective, observable facts, such as past management performance and an outstanding career, will return different results than a type of charisma that is not objective, but based on vague, unfounded expectations.

How can we define charisma that is based on vague, unfounded expectations? We can see such examples by looking at instances in which people believe that others are charismatic simply by sharing the same definition of charisma. This can be seen in the way that the families of chaebol chairpersons avoid media exposure, thinking that staying behind a veil of mysticism makes them seem aristocratic and charismatic.

Can we really say that third- and fourth-generation chaebol chairpersons have charisma based on tangible facts? Most have no record of their managerial prowess, and even if they do, it is full of failure. This is a far cry from the hardships, adversities and failures that the late Chung Joo-young faced as the founder of the Hyundai Group.

Few would believe that the inherent abilities of third- and fourth-generation CEOs helped them get on the fast track to the top.

We can only conclude that charisma stems from the legacy of their chaebol families. This explains how the charisma of a company’s founder differs from that of third- and fourth-generation chairpersons. It would be a stretch to say that the charisma of the latter will positively impact corporate performance.

Charisma of young chaebol leaders has different risks than founder’s

The problem is that things don’t stop here. When the company confronts a crisis, the CEO must deal with snowballing demands. In terms of a chaebol, that creates an opportunity for the third and fourth generations to chair the group.

CEOs who arise in times of crisis have a tendency to shake up the organization. Take Chung Yong-jin, who recently became chairman of the Shinsegae Group. During his tenure as vice chairman, Emart’s stock price has fallen 59% over the past five years and 70% over the past 10.

Despite doubts about his qualifications, Chung has basically seized upon a crisis in the retail industry as an opportunity to assume the chairmanship. The first step he took in his new position was pledging rewards for overperforming executives and discipline for underperforming ones. The new Shinsegae chairman appears to be lenient toward himself and strict with others, making for a mismatch of authority and responsibility.

Second, charismatic CEOs have a tendency to richly compensate themselves regardless of their company’s performance. A striking example of that is provided by Elon Musk, who may have to cough up about US$56 million worth of shares after losing a lawsuit filed by a shareholder. When the shareholder complained that Musk’s compensation package was overgenerous, Musk’s associates attempted to justify that by pointing to his superstar status. In effect, Musk was demanding to be paid for his charisma.

It’s typical for chaebol third and fourth generations to be compensated for their charisma. They rocket up to the chairmanship while boosting their compensation at every spot along the way on the grounds that only a charismatic person should serve as CEO. Some of them multiply their pay by simultaneously holding executive positions at several group affiliates as if they were some kind of all-knowing and all-powerful deity.

Third, charismatic CEOs have a tendency to spend a lot of time outside the office, chasing the attention of the public. That might mean getting involved with other organizations or going on a lecture series. Nowadays, the primary place for extracurricular activities is obviously social media.

Elon Musk is infamous for sticking his nose into a wide range of matters through social media. His Korean equivalent in this respect might be Chung Yong-jin. To be sure, there’s nothing wrong with the CEO having personal interests or social pursuits. The problem is when those activities reach such proportions that they detract from their primary occupation.

A fourth issue is that while external assessments of charismatic CEOs tend to be positive, those assessments are not very accurate. It’s common for analysts to recommend investing in a company because they believe its charismatic CEO has positive growth potential, only for the company’s performance to be disappointing.

In short, not only laypeople, who are limited in their knowledge of charisma and ability to gauge it, but also experts in the capital market overestimate charisma and make faulty predictions as a consequence.

These external assessments of charismatic CEOs and the hasty predictions that result are some of the main factors exacerbating the chaebol problem. If anything, the flock of experts often praises the charisma of chaebol leaders even more than ordinary people. (It’s unclear, however, whether such experts are genuine in their opinions or are actually driven by hidden business interests.)

While I’m not quoting from research findings here, I want to close this piece by mentioning two concerns I have. The third and fourth generations of chaebol families try to establish a role model for themselves — Elon Musk or Steve Jobs, for example. Despite their infamous personality quirks, these two figures have undeniably changed the world through technology.

In other words, there’s obviously something to their charisma. It’s because of their genuine achievements that we go easy on them despite their cruelty to colleagues and staff and their belligerence and attention-seeking behavior on social media.

But what about chaebol family members from the third and fourth generations who have risen to the rank of CEO without any notable achievements to their name? What if they too are cruel to their staff and prone to belligerence and attention-seeking behavior? They’re just adding to the company’s risks.

Pushing to cultivate charisma where none exists has certain downsides. For one thing, that requires achieving complete internal control. CEOs’ weapons of choice are rigid control of appointments and compensation. But that’s not the kind of mysterious charisma that wins people’s hearts, but ironfisted rule. That’s also typical of a backward governance structure.

If there were a member of the chaebol third and fourth generations who broke with that trend, I’d be happy to recognize them as a charismatic CEO, because they would be a leader who had successfully changed course on corporate strategy and culture.

By Lee Chang-min, professor of management at Hanyang University

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 3Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 4[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 5[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 6[Special report- Part III] Curses, verbal abuse, and impossible quotas

- 7Flying “new right” flag, Korea’s Yoon Suk-yeol charges toward ideological rule

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 10Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US