hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Soaring deposits and rent drive vulnerable groups to dismal living conditions

Kim Cheol-su, an unmarried high school graduate in his 50s, lives in a gosiwon, a kind of low-cost dormitory-style rental building. The rent for his unit, where he has been living for over two years, costs around 280,000 won (US$235.95). Kim’s hope is to be able to move into public rental housing. He doesn’t make much, but he sees it as possible if he saves up over the next 13 years or so.

Kim’s scenario is a fictionalized version of the residential environment for vulnerable residents in the Greater Seoul area as investigated by the Housing Welfare Foundation (HWF). Created with funding from the Korea Land and Housing Corporation (LH) to provide residential support for vulnerable persons, HWF published a report on “current housing conditions for vulnerable demographics” based on interviews conducted over a two-month period starting in June this year with 12,954 people (9,767 in Seoul, 2,405 in Gyeonggi Province, and 757 in Incheon) whose housing does not qualify as a “dwelling.” It was the third such study of so-called “non-dwelling residents.”

In 2017, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT) studied a sample population of 6,809 non-dwelling resident households to extrapolate the situation nationwide; in 2018, the National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRCK) conducted in-depth interviews with 203 non-dwelling resident households in Seoul/Gyeonggi Province (Bucheon and Gwacheon), other major cities outside the Greater Seoul area (Busan and Daejeon), and an agricultural community (Iksan in North Jeolla Province). The latest study is noteworthy in that the researchers individually sought out and interviewed over 10,000 of the estimated 190,000 non-dwelling residents in Greater Seoul.

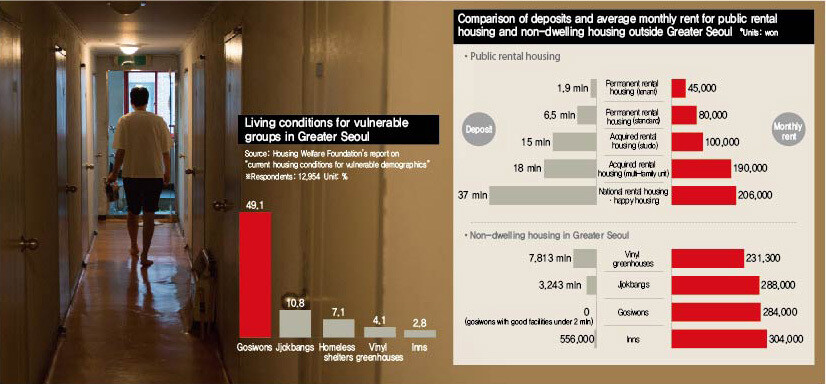

According to a copy of the findings shared by Youn Kwan-suk, a Democratic Party lawmaker and member of the National Assembly Land, Infrastructure and Transport Committee, a total of 5,608 interviewees (49.1%) among the 12,954 who took part in the survey were living in gosiwon units. Another 1,231 (10.8%) lived in “jjokbang” (slice rooms in a house), while 813 (7.1%) lived at a homeless shelter, 473 (4.1%) in a vinyl greenhouse, and 327 in an inn (2.8%). For the report, resident characteristics were analyzed for a total of seven forms of “housing,” which also included those who lived on the street (205, 1.8%) or in public baths (51, 0.4%). By gender, 70.4% of the non-dwelling residents were male and 29.4% female. Of the 6,322 who provided information on the number of household members, 3,374 (53.4%) lived alone, while 1,233 (19.3%) lived with another person and 864 (13.7%) lived in a three-person household. Over half of greenhouse residents (232, 51.7%) lived with a spouse.

Gosiwons were most frequently named as the respondents’ most recent previous residence. One in three (33.1%) answered that they had lived in a gosiwon. Another 36.1% said they had lived in regular housing before moving into their non-dwelling situation: 19.6% reported living in a detached home (including multi-family housing), 7.5% in multiplex housing, and 4.3% in an apartment.

High deposit/low rent vs. Low deposit/high rent

Major differences were observed in the relative stability and costs of residences. The average residence duration for a greenhouse was 10 years and one month; for a gosiwon, it was a relatively brief two years and 10 months. Other durations included seven years and 10 months for jjokbangs and three years and three months for inns. Greenhouses were most expensive, with an average deposit of 7,813,000 won (US$6,586), but had the lowest average monthly rent at 206,000 won (US$173.65). Jjokbangs costs an average of 3,243,000 won (US$2,734) for a deposit and 231,300 won (US$194.97) for rent; inns averaged 556,000 won (US$468.75) for a deposit and 304,000 won (US$256.30) for rent. Gosiwons had no deposit, with average monthly rent amounting to 284,000 won (US$239.44); not requiring a deposit was seen as an advantage of the gosiwon units.

Respondents paid an average of 270,000 won (US$227.63) a month in rent, which was roughly equal to the 280,000 won (US$236.06) paid for national rental housing and Happy Housing and more expensive than the averages for permanent rental housing (45,000 won, or US$37.94, for beneficiaries, 80,000 won, or US$67.45, for others) and acquired rental housing (100,000 won, or US$84.31, for a studio, 190,000 won, or US$160.19, for a multi-family unit). The situation was a tradeoff between more expensive rent and relatively inexpensive deposits. Deposits, which require a lump-sum payment at the time of occupation, are a stumbling block for vulnerable demographic members seeking to move into public rental housing.

Why people don’t move

Eleven percent said they had had the opportunity to move into a public rental apartment but gave up; 62.1% cited the “deposit costs” as a reason. Another 8.3% named the “absence of neighbors on familiar terms,” while 7.9% said the housing was “too far from work.” Acquired and key money-leased rental housing is also available with deposits under 5 million won (US$4,217), but the numbers suggest respondents are declining to move due to their close relationships with neighbors and proximity to their workplace.

Around one in four (25.8%) said they had “concrete plans” to move, while 54% said they had no plans to and 20% said moving was “more or less out of the question.” The average target amount respondents projected as necessary to move was 47 million won (US$39,639), which they predicted would take around 11 years to save up.

As the most essential residential welfare program, vulnerable residents named “affordable public rental housing availability” (46.5%). Another 24.9% of residents said they had family members whom they would live with if they moved into public rental housing, while 28.8% named “subsidies for monthly rent” and 11.7% said they hoped for an “installation plan for public rental housing deposits.”

Since June, MOLIT has been working to encourage vulnerable residents to move into acquired and key money-leased rental housing by lowering deposit costs or replacing them with rental arrangements. Members of the minimum income segment receiving livelihood and housing benefits are eligible to move into LH-supplied acquired and key money-leased rental housing without a deposit, while medical benefit recipients, single-parent families, and disabled households earning below 70% of the average income can have their deposits lowered by half. But the situation for non-dwelling residents is one in which relocating to acquired or key money-leased rental housing while maintaining the same living zone to enable self-support is practically difficult.

“People have trouble finding acquired or key money-leased rental housing in their own living zones, and many who do move in end up returning to jjokbangs because they miss their relationships with neighbors,” said Youn Kwan-suk on Oct. 16.

“One alternative may be to include the availability of constructed public rental housing and award priority occupation points to households that fall below minimum residential standards,” suggested Youn, who plans to hold a joint seminar with the HWF later this month to develop housing improvement policies for non-dwelling residents.

By Kim Tae-gyu, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 2Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 3Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 4Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 5‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 6[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 7N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 10Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South