hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

When did the US start taking Japan’s side?

Less than a month after President Joe Biden entered the White House pledging to repair the US’ system of alliances, the US has begun calling on South Korea and Japan to repair their relationship and to strengthen trilateral cooperation with the US. But the reality is that for South Koreans, the US’ actions look less like impartial mediation and more like siding with Japan.

Are Koreans correct in that impression? And if so, when did that trend begin?

Chung Eui-yong, South Korea’s new Minister of Foreign Affairs, had his first phone call with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken on Feb. 12 — that’s the Lunar New Year, one of South Korea’s biggest holidays. The timing suggests how eager the South Korean government is to speed up communication with the US.

“The two diplomats agreed to hold high-level talks as soon as possible to discuss pressing bilateral issues and agreed on the importance of continuing trilateral cooperation with Japan,” the Ministry of Foreign Affairs said in a press release announcing the meeting.

But the summary released by the US State Department was slightly different in tone. “Secretary Blinken highlighted the importance of continued U.S.-Republic of Korea-Japan cooperation,” the statement said, suggesting that the US had urged South Korea to quickly repair its relationship with Japan.

That impression was even stronger in the US State Department’s summary of Blinken’s phone call with Japanese Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi on Feb. 10. The US said that Blinken and Motegi “welcomed further regional cooperation, including through U.S.-Japan-ROK [South Korea] trilateral coordination and the Quad.”

But Japan only stressed that the two diplomats “shared the view to closely coordinate between like-minded countries towards the realization of a ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific,’ and also shared the view to steadily strengthen cooperation between Japan, the U.S., Australia, and India.” In short, the Japanese statement made no mention of trilateral cooperation with the US and South Korea.

There’s a sense in these statements that the US is asking South Korea to repair a relationship that has been damaged by diplomatic mistakes of some sort — and that Japan isn’t bothering to hide its grievances, as if its anger were justified.

US’s shifting role as mediator between Seoul and TokyoIn earlier spats between South Korea and Japan over the comfort women and other historical disputes, the US intervened in significant ways based on the value it places on human rights. Those interventions could be seen as working in the favor of South Korea.

For example, the US House of Representatives passed a resolution on the comfort women on July 30, 2007, despite persistent opposition from Japan. And on Dec. 26, 2013, the US registered its disappointment with then-Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s visit to the controversial Yasukuni Shrine.

But the US shifted its stance dramatically while it was upgrading its alliance with Japan in order to respond to the rise of China.

In March 2014, Abe said he would uphold the 1993 Kono Statement, in which Japan had acknowledged the involvement of the Japanese military in the recruitment of the comfort women and the compulsory nature of their recruitment. In April 2015, the US and Japan revised their guidelines for defense cooperation, upgrading their “regional alliance” into a “global alliance” with a greater status and scope of activity.

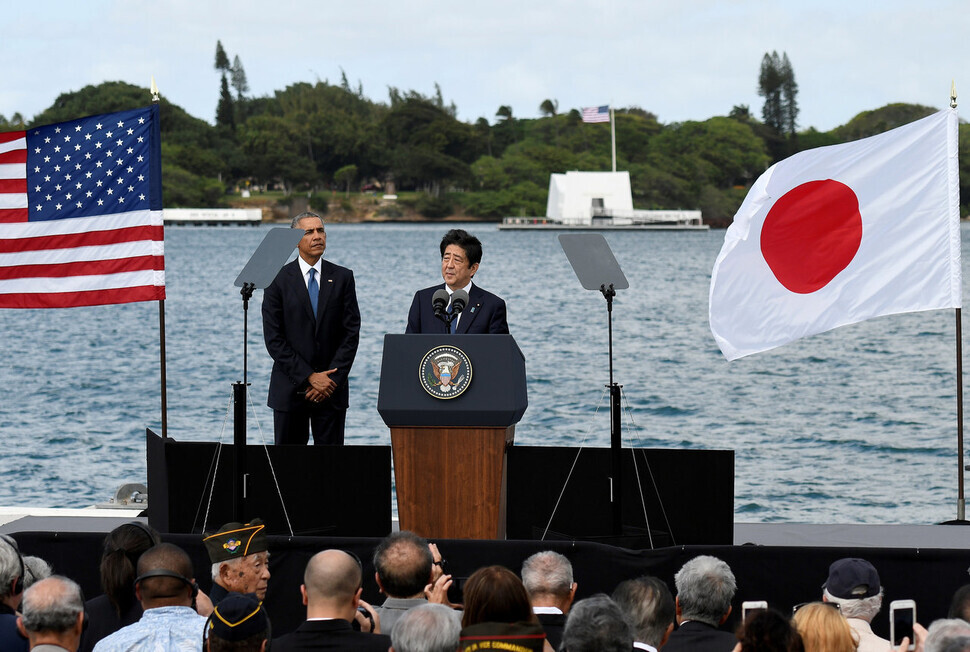

By exchanging visits to Hiroshima and Pearl Harbor in 2016, Abe and then US President Barack Obama largely succeeded in wiping away any lingering resentment over World War II. Those steps made the US-Japan alliance more special than it had been before.

As a result, the US changed its approach to intervening in historical conflict between South Korea and Japan. In early 2015, the US began overtly pushing for reconciliation between South Korea and Japan and said that it “welcomed” the comfort women agreement that they signed on Dec. 28, 2015.

Even Biden himself said during a phone call with Abe on Jan. 6, 2017 — while he was still vice president — that the US supported the comfort women agreement and hoped it would be faithfully implemented by both sides.

Believing that the conflict between South Korea and Japan had been concluded by the comfort women agreement, the US and Japan proceeded to take trilateral cooperation with South Korea to the next level. Japan and South Korea reached an intelligence-sharing agreement called GSOMIA in November 2016, and the US finished installing the THAAD anti-missile system at a US military base in South Korea in early 2017.

The US stance changed somewhat after Donald Trump’s inauguration as US president in January 2017. Trump gave short shrift to US alliances under his slogan of “America first.” Another way he broke with tradition was by holding three summits with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, in June 2018, February 2019 and June 2019.

During that process, the Moon administration invalidated the comfort women agreement in January 2018 and bickered with Japan in the fall of 2019. Moon initially decided to scrap the GSOMIA agreement with Japan, before ultimately backpedaling.

In 2018 and 2019, the US and Japan fleshed out their Indo-Pacific Strategy (which Japan calls the “Indo-Pacific Plan”), a joint initiative for encircling China. Since then, the two countries have been tightening up their quadrilateral security framework (called the “Quad”) with Australia and India.

The new Biden administration earnestly wants South Korea and Japan to engage in close and flexible cooperation to help rein in China. That was suggested in comments made by a US State Department spokesperson to Voice of America on Feb. 11. “Current tensions between Japan and the Republic of Korea are regrettable,” the spokesperson said, adding that no relationship is “more important than Japan and the Republic of Korea.”

In a report on South Korea-Japan relations and US-Japan relations, the US Congressional Research Service said that repairing South Korea-Japan relations was a top foreign policy objective for the Biden administration.

US intervention is expected to begin with Blinken’s tour of Asia, which will likely happen in March. CNN reported on Feb. 11 that Blinken will be visiting allies in NATO and Asia in mid- or late March, quoting multiple officials at the US State Department.

Following Yoshihide Suga’s election as prime minister of Japan in September 2020, the South Korean government has attempted to repair relations while proposing that the Tokyo Olympics this summer be used to advance peace on the Korean Peninsula.

But such efforts have been largely stymied by Japan’s adamant demand for concessions from South Korea. If the current impasse continues, Seoul may find itself forced to once again make a decisive concession in its relationship with Japan, just as it did when it signed the comfort women agreement in December 2015 and when it reversed its decision to scrap the GSOMIA agreement in November 2019.

By Gil Yun-hyung, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 4[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 5[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 6Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 7US exploring options for monitoring N. Korean sanctions beyond UN, says envoy

- 8Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 9US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 10[Photo] Smile ambassador, you’re on camera