hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

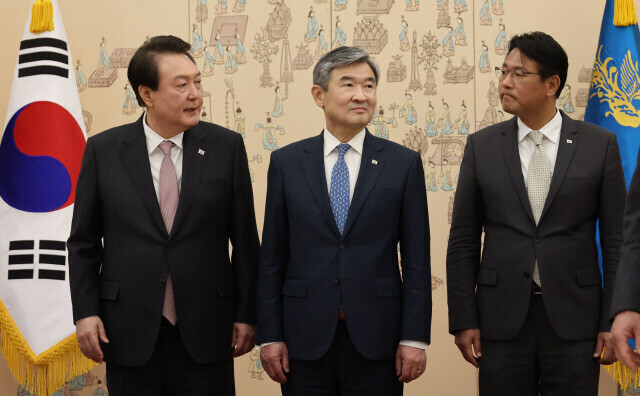

[Column] US spying confirms the risks of Yoon’s diplomacy

Even the best spy thrillers can’t top the cruel chills reality has in store for us. The CIA wiretapped and briefed the Pentagon on how top South Korean diplomatic and security officials were responding to Washington’s request for arms aid to Ukraine.

Someone, without anyone noticing, took photographs of classified documents and spread them online, giving the world a chance to take a not-so-sneaky peek into conversations held in South Korea’s National Security Office.

The New York Times and other news outlets reported that the leaked documents revealed that in early March, Lee Mun-hee, then-secretary for foreign affairs, told Kim Sung-han, the then-national security advisor, that ammunition given to the US might end up in Ukraine.

Lee also stressed that South Korea “was not prepared to have a call between the heads of state without having a clear position on the issue.”

Why were these authorities worried about a call between the two heads of state? If Yoon were to be consistent in South Korea’s position and state that “South Korea will not supply lethal aid,” there wouldn’t have been a problem.

It seems that the parties involved were worried that Yoon, giddy with excitement over his upcoming state visit to the US, would go ahead and promise: “Yes, South Korea will supply ammunition to Ukraine. I’ll take responsibility.”

It’s easy to imagine such a scenario unfolding. Just think about all the times that Yoon took the initiative to make his own decisions on issues — such as the compensation for victims of forced labor during Japanese colonialism, and issues concerning the bilateral relationship between South Korea and Japan.

Even though diplomatic and security officials urged him to not go ahead with “quick fixes,” Yoon barged forward. Yoon’s dogmatism now poses a huge risk for South Korea’s diplomacy.

We’ve even lost the voice of moderation in the room, as the two people who demonstrated such a stance, Kim Sung-han and Lee Mun-hee, have both resigned over supposedly fumbling of a proposal for a Blackpink concert — an excuse which I doubt anyone finds truly convincing.

Now the power of the NSO rests in the hands of its first deputy director, Kim Tae-hyo. Those in diplomatic circles say that Yoon calls on Kim Tae-hyo five or six times a day.

Once removed from his post during the Lee Myung-bak administration for pushing too strongly for security cooperation with Japan, Kim Tae-hyo is now pushing even further than before. On March 18, just days after the South Korea-Japan summit, he appeared on broadcaster YTN and stated that he “didn’t want a negotiation that involved a give-and-take situation,” and that Japan first proposed the “long-awaited solution” to most of the diplomatic issues between South Korea and Japan.

He also added, “If the global community, including the US, thought that ‘South Korea is different from the past’ in 2018, I want to make them feel that now. This is a ‘rebirth’ of South Korea in the international community, both morally and nominally.”

The Yoon Suk-yeol-Kim Tae-hyo doctrine demonstrated goes like this. First, vehemently oppose anything that has to do with Moon Jae-in’s foreign policies, i.e., “anything but Moon.” Second, continue to appeal to both the US and Japan even on occasions meant to appeal to and convince the South Korean public.

While Moon’s foreign diplomacy policies were at odds with the US and Japan, Yoon’s “born again” administration is determined to make diplomatic policies that the US and Japan can trust.

Third, the safeguards of South Korea’s foreign diplomacy are crumbling as the president pushes the hard-line rhetoric of Kim Tae-hyo, stating that he, the president, will bear the responsibility.

Fourth, since the US and Japan are no longer estranged, instead of the fierce games of tug-of-war, South Korea’s diplomacy is becoming more privatized, with an emphasis on the presidential couple’s ceremonies and events.

Equating South Korea’s national interest with that of the US and Japan is already showing some side effects: Diplomacy with China has all but been forgotten.

The imperialist threat posed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompted many countries to strengthen national security cooperation with the US, but, at the same time, they are wary of US protectionism and unilateralism. South Korea’s current diplomatic strategy is going against the trend of complex diplomacy.

South Korea should, at least, properly evaluate its policy with Japan. Early in April, Japan’s foreign minister, Yoshimasa Hayashi, visited China to criticize Beijing for escalating tension in the Taiwan Strait and the East China Sea as well as to demand the release of Japanese citizens held in China on espionage charges.

On the surface, the talks did not end with any concrete conclusions, and tensions were high. However, top figures in Chinese diplomacy, Premier Li Qiang, Politburo member Wang Yi, and Foreign Minister Qin Gang, all met with Hayashi for a lengthy exchange of views.

As China digs deep to improve its external relations in a bid to shore up its economy, Japan is trying to manage its relationship with China and to expand its opportunities. As Japan strengthens its international standing as a key US ally, it’s fast at work around the world working on its interests.

The more serious the North Korean nuclear and missile threat grows, the more important it is for South Korea to pursue strategic exploration to find out if China has completely abandoned its support for denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula or whether there is room to persuade Pyongyang by route of Beijing.

The surging trade deficit with China is largely due to China’s policy shift toward self-sufficiency, but South Korea should manage its relations with China to reduce the impact.

South Korea should also assess and prepare for a possible crisis in the Taiwan Strait. Simply believing that following the guide of the US and Japan will solve South Korea’s challenge is not a feasible national strategy.

Kim Tae-hyo will visit the US on Tuesday to finalize the agenda for the US-South Korea summit. If South Korea once again refuses to participate in a “give-and-take” with the US, and makes generous concessions regarding key issues such as the semiconductor issue to the US, what will South Korea’s future look like?

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 3[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 4S. Korea, Japan reaffirm commitment to strengthening trilateral ties with US

- 5[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 6Japan officially says compensation of Korean forced laborers isn’t its responsibility

- 7[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- 8[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- 9Why Israel isn’t hitting Iran with immediate retaliation

- 10[Interview] Learning about the Sewol tragedy through BTS