hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special series] If Korean youth were 100 people

In the media narrative, “Korean youth” is taken to mean “students at four-year universities in Seoul.” Youth mainstream is said to be students at the prestigious institutions known as “SKY”: Seoul National University (SNU), Korea University, and Yonsei University. What those students say comes to represent the opinion of “youth nowadays.” The question of university admissions boils down to how those top universities select their students. The books most frequently checked out at their libraries are thought to define reading trends among people in their 20s. For a student to quit one of those universities becomes front-page news. In actuality, the carefully curated and highly symbolic Korean word of “youth” overrepresents some and underrepresents others.

A prime example of this interest bias was the controversy over the nomination of Cho Kuk as Justice Minister. Students at the pinnacle of a hierarchical university system were quoted day after day in the print and TV news. The outrage of SNU and Korea University students about the accusations that Cho’s daughter had gotten illicit help with her college application was reported in the press as the “rage of 20-somethings.” The term chosen as a touchstone for that rage was “fairness,” taken to mean the desire for students to be “ranked fairly according to their ability and treated accordingly.”

This “fairness” narrative was powerful enough to scuttle a reform to the university entrance program that had been painstakingly designed through a process of public debate just one year earlier. Even though the Education Ministry’s “plan to enhance the fairness of the university admission system,” announced on Nov. 28, only applies to 16 universities in Seoul, the press expansively interpreted this as the “return of the Suneung” – Korea’s College Scholastic Ability Test – “after a hiatus of 20 years.” Our reflections on this type of overrepresentation, and our conviction that it ought to be corrected, were the inspiration for the “100 Korean youth” reporting project.

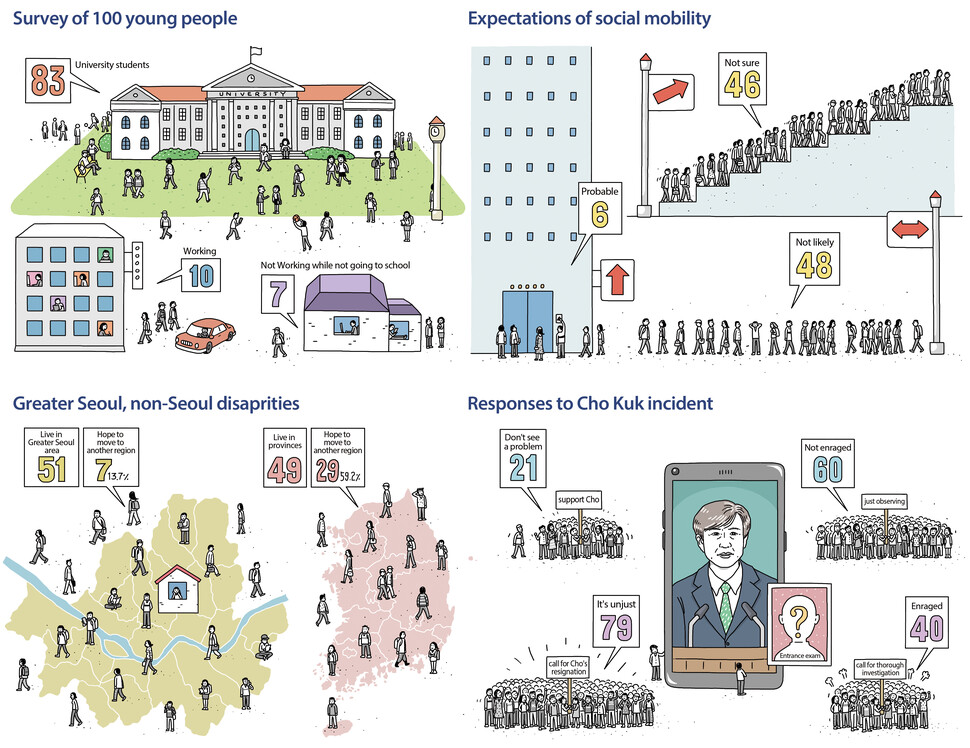

At its heart, this project aims to shift the focus away from male students at four-year universities in Seoul from households with median income or above. Toward that end, we decided to view Korean youth in 2019 from a wide-angle lens. We met with 100 young people between the ages of 19 and 23 from across the country to administer a detailed survey and in-depth interviews.

We selected these individuals with a focus on the categories of universities they attend and the percentage who were hired immediately after high school graduation, based upon a wide range of statistics, including the 2015 census and data from the Korean Education Development Institute. We also took regional representation and the gender ratio into account. The reason we focused on the type of university is because, at least at the present moment, we regard this as one of the biggest factors determining young people’s future.

Perception of university students outside Seoul vs. those in SeoulThese ratios led the Hankyoreh to meet with 29 students from private universities outside Seoul, 28 students from two-year colleges outside Seoul, 16 from universities in Seoul, 10 from national universities outside of Seoul, 10 who are working or self-employed, and seven who are unemployed or fall in other categories. After creating this microcosm of Korea’s youth, only 2% of “youth nowadays” were students at SKY. Since our goal is to give a voice to the 98 students who have been previously ignored, the Hankyoreh didn’t include the “two” SKY students in the 100 it met. Additionally, 18 young people aged 24 and above whom the Hankyoreh met over the course of reporting were omitted from the questionnaire but included in the in-depth interviews.

In order to line up the hundred youth, four Hankyoreh reporters made cold calls to perfect strangers and begged them to join the cohort. While many turned down the offer, others fortunately accepted – and in those cases, the reporters packed their things and headed in their direction. In total, the four reporters traveled 10,000km on this story.

Meeting the 100 youth had a number of unexpected results. While half of the 16 students from four-year universities in Seoul hope to be hired by a large corporation, that was only true of two of the 29 students at four-year universities outside of Seoul. Thirty thought that people are compensated fairly for their effort, while 70 said they didn’t think so. Six said they have good chances of moving up the social ladder, while 46 said their chances are only fair and 48 said that wasn’t likely to happen.

Of 50 men, 38 are planning to get married, while 16 aren’t planning to have children. But fewer women are planning to get married then men – just 30 of 50 – while 29 don’t intend to have children, nearly double the number for men. And while 79 of the hundred said that the alleged steps taken to help Cho’s daughter get into university were unfair, 60 of 100 said that didn’t make them angry, an unexpected outcome.

Our wide-angle view provided fresh confirmation of the regional disparity among youth. A substantial number of young people living outside the capital region said they want to leave their hometown and move to a big city. The general reasons they gave for this desire was the lack of jobs and cultural opportunities at home. The desire for life in Seoul, with its abundant opportunities, was particularly strong among youth who’d been to the capital or have relatives living there.

The trouble with clumping all young people into one category“This should be seen not as a youth issue but a regional issue. National development failed to achieve a balance among regions, and the resulting problems fall on the shoulders of the youth,” said Kim Ji-gyeong, a researcher at the National Youth Policy Institute. All resources tend to gravitate toward Seoul, creating a vertical stratification between the capital region and the provinces.

Most importantly, we realized several times during our reporting that, despite having planned the “100 Korean youth” project, we still have our own prejudices. We’d assumed that high school graduates who never went on to university, students at two-year colleges, and students at universities outside of Seoul would be filled with despair and have no dreams about the future. But despite living in “Hell Joseon” and being part of a generation putatively forced to abandon many things older generations took for granted, and despite being apparently frustrated and hurt by regional disparity and the preference shown to students from elite schools, most of the youth we interviewed were optimistic that their future would be better than their present (69 of 100).

Our mistaken assumptions were due to a sort of inertia, our tendency to focus on the particular image of young people discouraged by their unhappy reality, an image highlighted by popular narratives about young people stuck in low-income jobs and thus frozen out of the typical Korean narrative of the good life. There were hopeful signs that young people would quickly recover their resilience, as long as the structural issues that frustrate them can be rectified. Just as the press has a tendency to overrepresent youth at major universities in Seoul, putting the sole focus on youth frustration may be another blanket generalization.

While planning this series, we turned to experts for advice, and they endorsed our plan to meet a wide variety of young people. But Kim Seon-gi, a researcher for the Sinchon Centre for Cultural-Politics Research and author of “Youth-Selling Society,” had a different suggestion: “It might be better to say that there’s no such thing as ‘youth.’” Kim has taken issue with the current youth narrative, which regards young people as representing a discrete group.

“’100 Korean youth’ represents a step forward because it seeks to trace the fault lines inside that generation, but we’re still left with the fundamental question of why we can’t beyond the concept of ‘youth,’” Kim Seon-gi said.

That’s a fair point, one that was echoed by Kim Ji-gyeong. “The young generation today is too differentiated for us to identify many intragenerational tendencies,” she said.

And indeed, it was difficult to derive meaningful tendencies from the diverse responses provided by the 100 young people. Partly to blame is the fact that we have only viewed the generation through the lens of youth and haven’t sought to consider the range of identities found inside. That’s why we haven’t highlighted statistics in these articles, even though there were more than 100 questions in the detailed questionnaire we administered to all 100 young people.

Perhaps the “youth” that have been explained and portrayed by the youth narrative for so long are already gone.

By Suh Hye-mi, Kang Jae-gu, Kim Yoon-ju, and Kim Hye-yun, staff reporters

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 2Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 3[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 4Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 5Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 6N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 7[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 8Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South

- 9[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 10Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan