hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Administration’s expediency shaking the rule of law in S. Korea

By Um Sung-won staff reporter

When the executive abuses its authority to enact enforcement decrees that subvert the laws they are meant to enforce, it is the public that bears the brunt of the damage. The reason for this is the likelihood that the chief executive, the President, will quietly craft policies to the administration’s own liking, while the stakeholders without a powerful lobby behind them will have difficulty reflecting their own interests through the traditional route of the National Assembly. The same public majority that is supposed to hold sovereignty ends up being excluded from the political process.

■ Tools for Union Suppression

Enforcement decrees are often used to overpower the law for political ends. Perhaps the most prominent recent case of this was the decision to strip the Korean Teachers’ and Education Workers’ Union (KTU) of its legal status. That Oct. 24 decision by the Ministry of Employment and Labor was based on Article 9, Item 2 of the enforcement decree for the Trade Union and Labor Relations Adjustment Act, which states that an established union “must be notified that it is not viewed as a labor union according to the law” if grounds for rejecting its application are discovered and it does not respond within 30 days to a request to take corrective action.

No provisions for declaring a union “not a union” can be found in the actual Trade Union Act itself. This explains why the Vice Minister of Employment and Labor Lee Jae-gap told a conservative group demanding the revocation of the KTU’s legal status last February that “a legal examination of the enforcement degree suggested a strong possibility of unconstitutionality.” That same, most probably unconstitutional decree is what ultimately led 60,000 KTU members to lose their union.

■ Rushing Through Wasteful Projects

An enforcement decree to the National Finance Act was used to help the Lee Myung-bak administration (2008-Feb. 13) to speed through the Four Major Rivers Project without any preliminary feasibility study, at a time when the public was skeptical about Lee’s ideas for a “Grand Korean Waterway.” Researchers with the Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements (KRIHS), asked to come up with a master plan, told the government it would be better not to conduct an economic feasibility analysis, saying that benefit/cost figures could “raise questions about their appropriateness.” In the end, the Ministry of Strategy and Finance added a “disaster prevention” provision into Article 13, Item 2 of the act’s enforcement decree, which listed exceptions to the feasibility study requirement. This allowed key parts to the project - weir building and dredging - to escape any preliminary examination.

In February 2012, Busan High Court ruled to cancel the Four Major Rivers Project, making public the Lee administration’s decision to arbitrarily add provisions to the enforcement decree that actually contradicted the law the decree was supposed to enforce. It also said that the decree “went beyond the scope” of the law. It was the modification of a single decree that led to a huge dent in national finances. Experts recently gave the 22 trillion won (US$20.7 billion) spent on the project as one of the key reasons welfare spending policies for the working class have been recently on the wane.

■ Business World Calling the Shots

Another concern when the government’s administration legislation has a strong effect on citizen lives is that the policies it creates favor only those who are already powerful.

“Unlike the National Assembly’s legislative process, enforcement decrees only have to go through the Cabinet, which makes it much more vulnerable to industry lobbying,” said Lee Eun-gi, a professor at the Sogang University law school.

An enforcement decree is what neutralized an amendment to the Electronic Financial Transaction Act that is set to go into effect on Nov. 23. Article 9 of the act says that financial companies are responsible as a rule for hacking and other forms of electronic transaction fraud. But Clauses 3 and 4 in Article 8 of the planned enforcement decree submitted by the Financial Services Commission counter this aim by granting broad and vague exemptions to the companies.

“According to the enforcement decree, financial companies would be able to escape responsibility by claiming that they set up security procedures and the victims didn’t use them,” said Kim Gyeong-hwan, an attorney with the law firm Minwho. “Meanwhile, the victims lose almost any chance of compensation from the financial company.”

Kim said that the enforcement decree defeated the purpose of amending the act in the first place. “The aim of the law is to provide financial company compensation to victims, but the enforcement decree is designed entirely to remove the company’s responsibility,” he explained. “Thanks to that decree, the hard-fought amendment to the law is basically pointless.”

■ Ruling Party: Tail Wagging the Dog?

Enforcement decrees that supersede the laws they enforce are essentially a case of the executive undermining the legislature. But sometimes legislators in the ruling party are complicit in the process. A case in point was seen with the Toxic Chemical Substance Control Act, enacted last May and June to prevent damages from germs in humidifiers and chemicals such as the hydrofluoric acid leaked at factories in Gumi, North Gyeongsang Province. The enforcement decree presented by the administration and ruling Saenuri Party (NFP) on Sept. 24 raises serious questions about what preventive effect the law can be expected to have.

The law itself assessed fines of up to 5% of the company’s annual sales for any chemical leaks that occur. But the decree creates rigid conditions for assessing a fine and applies them only to companies implicated in deliberate or repeated leaks.

“Even the parent law commutes a suspension of operation into a simple penalty,” said Jeong Nam-sun, an attorney with the Environmental Law Center. “In contrast, the discovery of just one usability period violation results in a 15-day suspension. The regulations are so weak that they could fatally undermine the whole purpose of the law.”

■ Avoiding Limits on Delegated Legislation

The enforcement decrees are implicated in a host of social issues. The problem begins with the fact that the executive is adding provisions into the lower laws that exceed or contradict the legal regulations enacted by the legislature in the higher law. In essence, it is skirting the limits on delegated legislation.

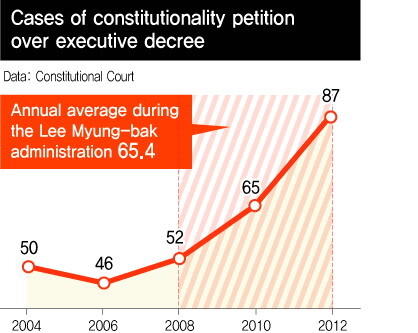

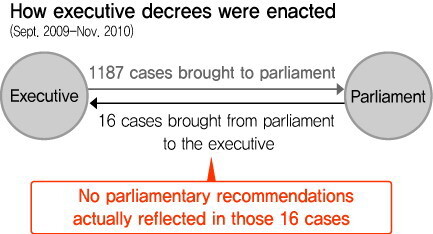

The problem worsened under the Lee administration, posing a dire threat to the principles of South Korean democracy. On Nov. 3, the Constitutional Court published a report on the constitutionality petitions it received over enforcement decrees and guidelines enacted by different agencies of the executive. An average of 48.8 petitions per year were collected under the administration of President Roh Moo-hyun (2002-07). Under Lee, his successor, it was up to 65.4. As of September this year, a total of 73 petitions had been received, suggesting the enforcement decrees are poised to turn into a major social issue.

“President Park Chung-hee (1962-79) used the oxymoronic term ‘administrative democracy,’” said Park Sang-hoon, president of Humanitas and a doctor of political science. “The idea was that because politics is so wasteful and clamorous, the executive has the authority to work in the nation’s interest. The situation right now is reminiscent of that expression. What we’re seeing is an ironic situation where the National Assembly is failing to perform its role as the legislature, while the executive is taking an authoritarian approach to governance.”

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 4[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 5‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 6[Reportage] On US campuses, student risk arrest as they call for divestment from Israel

- 7[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 8Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 9[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 10Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?