hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Why do struggling Korean workers stick it out in aerial protests?

Across Korea, people are taking to the sky to protest.

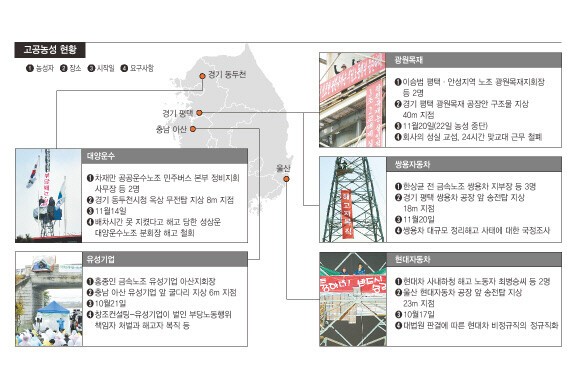

Including Choe Byeong-seung, 36, a dismissed Hyundai Motor irregular worker who climbed an electricity pylon in front of the Ulsan factory and started his sit-in on October 17, aerial protests by workers are taking place in five places around Korea. With the exception of Lee Seung-beom, 35, of Kwangwon Lumber, who ended his two-day sit-in when the company decided on the morning of Nov. 22 to resume negotiations, there is no way to know when they will set their feet back on the ground. Early in the day on Nov. 22, Hankyoreh reporters visited the sites of these protests in Pyeongtaek, Dongducheon, Asan, and elsewhere in Korea, to hear why these people started their dangerous ascent.

On Nov. 20, Lee climbed more than 50m in the air on some machinery at the Kwangwon Lumber factory in Pyeongtaek, Gyeonggi Province. Lee is the leader of the Kwangwon Lumber chapter of the Pyeongtaek-Anseong Regional Labor Union, a member of the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU). Clinging to the top of the structure 1m wide with no railing and breathing in the smell of wood and formaldehyde, he held out for two days.

On Nov. 22, Jeong Mi, 43, leader of the Pyeongtaek-Anseong Regional Labor Union, brought Lee news that they had reached an agreement with the company. Wrapped in a thick jacket and wearing a wool cap, Lee carefully stretched out his legs, which were stiff with the cold, before returning to the ground.

“All you need is some booze, right?” Jeong asked with a smile. “Kimchi stew,” said Lee, thinking of his shivering body and empty stomach.

At plywood manufacturer Kwangwon Lumber, the workers had been assigned to a 24-hour two-shift system. The union requested that the company switch to three shifts, as the Labor Standards Act prohibits more than 12 hours of overtime a week. At the same time as it began negotiations, the union filed a lawsuit against the company for unfair treatment of workers. At this, the company walked away from the negotiations. At a workplace with more than 70 employees, no more than 16 had joined the union, which lacked the strength to fight back when the company refused to negotiate. Lee resorted to the aerial protest. It was only then that the company returned to the table and finally accepted the union’s demand for three shifts.

While the number of workplaces with ongoing aerial protests decreased from five to four when Lee came down on Nov. 22, the remaining stories taking place in the sky are every bit as desperate as his was.

“Reinstate Unfairly Terminated Workers!”

The words are on a banner flapping from the 8m-tall steel radio tower located on the roof of the three-story Dongducheon City Hall. On the tower is Cha Jae-man, secretary general of the maintenance chapter of the Democracy Bus Office, which is a chapter of the KCTU and the Korean Public Service and Transportation Workers’ Union. He is joined by one other in the aerial protest.

The protestors have been sitting-in since Nov. 14, calling for the reinstatement of Seong Sang-un, 52, the president of the Daeyang Transportation chapter of the KCTU. In July 2012, the labor union was formed at Daeyang Transportation, which employs 73 bus drivers. Five people joined the union. The very next day, a rival union was organized by management, which about 50 workers joined.

Seong, the chapter leader who had founded the KCTU union at Daeyang Transportation, was fired on Oct. 4. He was told the reason for his dismissal was that he had failed to follow the bus schedule. After that, two members left the union and one quit the company. With Seong unable to fight for himself, executives from the sponsoring organization, the Korean Public Service and Transportation Workers’ Union, stepped in and started the protest.

“It’s definitely possible for a bus driver to fall behind schedule if he’s making an effort to obey the traffic lights,” Cha said, staying in his sleeping bag to keep warm. “Since they used such a flimsy excuse to fire him, it seems obvious that this is an attempt to oppress independent labor unions. We couldn’t make any progress despite 33 days of negotiations, so we came up here.”

Someone is dangling from a 5m high underpass next to the Yoosung Enterprise Co. (YPR) factory in Asan, South Chungcheong Province. On top of the underpass is an eight-lane highway; below it is a four-lane road. The bridge is always jittery from the cargo trucks that constantly roar by above and below. Tied by rope to the bridge railing is a plywood platform that measures 2m long and 1m wide. This is the site of Hong Jong-in’s aerial protest. Hong, 39, is leader of the YPR Ansan chapter of the Korean Metal Workers’ Union.

“A parliamentary audit revealed in October that the shutting down of the workplace last year was an illegal attempt by the company and Changjo Consulting to bust the union,” explained Hong. “Despite that, no one from management has been punished for breaking the law.” Starting in May 2011, the union filed 23 complaints about the company’s unfair treatment of workers with the Ministry of Employment and Labor, but the case was not sent to the public prosecutors until September 2012. Who knows when the investigation will be completed and a decision made? For Hong, who has been demanding that the company be punished, there was no alternative to the aerial protest.

Choe Byeong-seung, dismissed from his job as an in-house subcontractor with Hyundai Motor, has been protesting atop an electricity pylon in front of the Ulsan Hyundai factor for 37 days. The first time that he entered the courtroom was when he claimed that he had been wrongfully dismissed in March 2005. In July 2010, and again in February of 2012, the Supreme Court ruled that his dismissal was invalid. The court reasoned that, “as Choe was employed illegally as a dispatch worker, Hyundai must treat him as a regular worker.” But the company still hasn’t reinstated him.

While Choe was the first among the five aerial protesters to start climbing, he is actually more concerned about the others than himself. During a phone conversation with a reporter on Nov. 22, he asked that the Hankyoreh “pay attention to the workers dismissed by Ssangyong Motor who are staging an aerial sit-in in Pyeongtaek.”

The workers fired by Ssangyong Motor climbed a pylon in front of the factory in Pyeongtaek on Nov. 20, calling for “a parliamentary investigation into what has happened at Ssangyong.” When Hankyoreh reporters visited the site of the protest on the morning of Nov. 22, it was crowded with police officers, firefighters, and KEPCO and Ssangyong

employees. A scuffle had broken out over the idea of installing scaffolding for the safety of the protestors. Before they had begun the aerial protest, the dismissed employees had never gotten this much attention from the authorities.

Workers began to take to the sky around 2000, when the labor deregulation policies begin in earnest with increasing numbers of layoffs and companies using irregular workers. Regular employees working at huge factories were the first to start climbing. Kim Ju-ik, a union head at Hanjin Heavy Industries, staged an aerial protest for 129 days in 2003 from the top of Hanjin crane #85 in Busan, calling for the reinstatement of laid-off workers. Leaving behind him a note that called Korea “a country where you have to sacrifice yourself so that workers can live a decent life,” Kim ended his own life atop the crane.

Irregular workers were the next to try aerial protests. In 2008, Oh Mi-seon, 33, climbed up a 40m lighting tower in front of Seoul Station and staged an 18-day sit-in. At the time, Oh was the leader of the KTX crew chapter of the Railway Workers’ Union.

“For three years after being fired, I did everything that could be done. Making my appeal from on top the metal tower was the only choice I had left. I went up, not buoyant with hope, but weighed down with despair,” Oh said as she recalled the experience.

In the same year, Lee Dae-woo, 38, head of the GM-Daewoo irregular workers’ chapter of the Korean Metal Workers’ Union, climbed the closed circuit camera control tower in front of Bupyeong District Office in Incheon. He called for the “reinstatement of dismissed irregular workers” during the 71 days of his aerial protest. And even after that, irregular laborers kept climbing the steel pylons and the observation towers: dismissed employees at Rocket Electric, irregular employees at Koscom, and subcontractors at Daewoo Shipbuilding.

Aerial protests by workers are a kind of demonstration that is only seen in Korea. In other countries, members of environmental organizations occasionally climb trees in protest, but there are hardly any examples overseas of workers climbing up metal towers for indefinite sit-ins. What is the background for such demonstrations? Experts point to the absence of healthy communication between laborers, management and the government; no serious punishment for irregular and illegal behavior by corporations; a decline in the influence of labor unions due to drops in membership; and the absence of political parties that represent workers.

“These aerial protests by laborers function like the shinmungo drum during the Joseon Dynasty, which people tolled when they wanted justice,” said Dr. Bae Gyu-shik, labor relations and social policy research division head at the Korea Labor Institute. “Workers today have no way to cope with their sense of injustice, so they use these protests to share their dilemma with others.”

“Unlike Europe, which allows workers to achieve their interests through political parties and labor unions, in Korea those avenues for change are completely blocked,” said Jo Don-mun, a professor of sociology at Catholic University.

“Workers here are forced by external forces into extreme forms of protest such as aerial protests.”

For the time being, the protestors in the sit-ins continue to bear the force of the early winter wind whipping from above, and there is no telling when they will come down. All of the protestors at the four sites have indicated that they will stay where they are until the situation is resolved.

Changwon National University graduate school of labor professor Shim Sang-wan said, “Until corporations begin to initiate dialogue with the unions, and until there is political reform that allows the opinions of workers to be reflected in policies, the number of workers climbing towers will continue to increase”.

Please direct questions or comments to [englishhani@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 4[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 5US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 6Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 7[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- 8[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 9All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 10[Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism