hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Dutch veteran thanks S.Korean prison guard

Kim Hyo-soon, Editor at large

“How did you know where to find me? This is a miracle....”

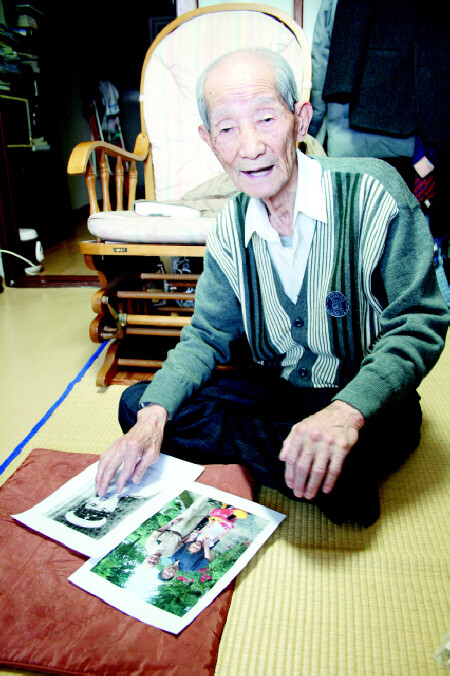

Ninety-four-year-old Park Byeong-suk, who lives in a working-class apartment in Seoul’s Nowon District, was unable to speak after hearing the unexpected news from Japanese visitors who came to his home on Dec. 28. They told him that a Dutchman who had been a prisoner-of-war of the Japanese military during the Pacific War was looking for Park, whom he credited with saving his life.

The three visitors, who included Waseda University Graduate School Visiting Professor Aiko Utsumi, had been working steadily over the years to support Korean Class BC war criminals who were tried by the Allied military tribunal and punished on charges of abusing POWs while stationed in Southeast Asia during the war as camp guards for the Japanese military.

They were visiting Park’s home because they had not forgotten the earnest entreaty of a Dutchman who had labored as a prisoner-of-war (POW) on the construction site for the Burma Railway, which would serve as the backdrop for the film “The Bridge on the River Kwai.” This railroad was intended to connect Thailand and Burma and ensure a transport route for a Japanese invasion of India, and hundreds of thousands of local residents and Allied POWs were mobilized to build it. It was called the “death railway,” as some 12,619 of the 62,000 Allied POWs sent to work there would perish.

Felix Bakker, 86, who currently lives in the Netherlands, believed that he survived the experience through the help of Park, and he worked over the years to locate his benefactor, who was long known by the Japanese name “Takemoto.”

While advanced in age and hard of hearing, Park was still strong enough to go on periodic outings. Once he began to catch on as to the reason for the Japanese visit, he told a painful story from the colonial era that he had kept even from his children.

“I barely made it back alive. My body was in such poor shape from being in the tropics for so long. After Liberation, something happened and I could not go back right away.”

Park was born into a poor farming family in Muan Township in South Gyeongsang Province’s Miryang County. The second oldest male among two brothers and five sisters, he took on the role of feeding his younger siblings at a young age when his older brother was unable to tend to their welfare. He graduated from a normal school in his hometown and worked in agriculture for one year before heading to Busan and making a living as a clerk for the Japanese company Marui. It was at this time that he responded to an announcement recruiting POW guards for imperial Japan. Beginning in June 1942, the 3,223 colonial youths selected received three months of training at Busan’s Noguchi Unit, after which they boarded transport vessels bound for various parts of Southeast Asia.

In October 1942, Park was assigned to an outstation affiliated with Thailand’s Ban Pong No. 2 Camp. Many of the POWs there were British prisoners who had surrendered in Singapore and the Malay Peninsula early in the war. One day, Park slapped a British officer with whom he was arguing after a continued delay in the loading and unloading of supplies. This would become the grounds for his arrest on POW abuse charges after the war, which prevented him from heading home to Korea. At a court-martial in Singapore in the fall of 1946, he was sentenced to two years in prison. His charges were relatively light, given that a substantial number of the 148 Korean POW guards found guilty on POW abuse charges received death sentences or life imprisonment.

Returning home four years after his departure, he found his home in shambles. His wife, whom he had parted with seven months after their marriage, had already passed away. He remarried a woman named Han Gi-sun, who had come back to Korea after suffering the atomic bomb attack on Hiroshima. Han, who was ten years Park’s junior, passed away herself a few years ago. They were a couple who experienced a stormy existence, one serving time overseas on unjust charges of war crimes, and the other suffering the ravages of the atomic bomb. Park’s experience as a POW guard is not one that he wishes to recall. Despite difficulties making ends meet as a basic livelihood security recipient, he did not apply for recognition as a victim with the Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization under the Japanese Imperialism.

Utsumi gave word on behalf on Bakker, saying, “You have lived a long and healthy life, and we hope you can meet this Dutchman who is looking for you so intently.” Park was overwhelmed with emotion, and at the same time confused. He recalled that there were Dutch in addition to the British who accounted for the majority of the prisoners, but his memory was faint.

In early 2011, Park and Bakker exchanged e-mails through the multi-stage relaying of the activists, indirectly exchanging photographs and inquiring after one another’s welfare. After seeing a photograph of Park from his younger days, Bakker confirmed that this was the man he had been looking for. He expressed happiness that Park had lived such a long life and wished blessings on his family. Park saw a photograph of Bakker taken just after conscription and recalled showing concern for the young Dutch prisoners. He expressed appreciation for Bakker’s sincerity in not forgetting him. The scene was like a movie come to life, with two men who met as POW and guard more than sixty years before on the Death Railway construction site coming together in the last years of their life to verify each other’s existence and exchange warm emotions.

Please direct questions or comments to [englishhani@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 346% of cases of violence against women in Korea perpetrated by intimate partner, study finds

- 4Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 5‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 6[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 7Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 8Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 9“Parental care contracts” increasingly common in South Korea

- 10[Interview] Dear Korean men, It’s OK to admit you’re not always strong