hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Feature] Looking back on the generation that brought democracy

There is a picture, its colors faded. A young man stands bleeding from his head, embraced by his friend. In the backdrop unfolds the Yonsei University campus, thick with tear gas.

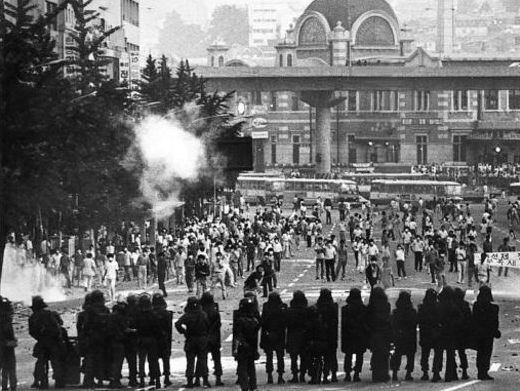

It was exactly 20 years ago that Yonsei student Lee Han-yeol died in a demonstration, in turn protesting the torture death of Seoul University student Park Jong-jeol. In those times, countless youths suffered and were sacrificed at the hands of South Korea's military dictatorship, and their classmates took to the streets to make their dreams of democracy a reality.

This New Year's however, the democratic movement activists of two decades prior find themselves confronted with invective and malice. The so-called 386 Generation that flooded the streets in 1987, having since taken the helm of South Korea's government, is now condemned as incompetent, responsible for the nation's downfall. These men and women were called the 386 Generation because they were born in the ’60s, entered college in the ’80s, and were in their ’30s when the term was coined.

Meanwhile, those who took the side of the dictatorship now openly call for a reevaluation of history. Just as was true 20 years ago, the buzzwords of today are "chaos" and "conflict." The only revision necessary is to switch "dictatorship" for "inequality."

What has gone wrong? The dictatorship was shattered in 1987 when a direct electoral system was installed, the Korean Federation of Trade Unions was established, and civil society took root. Yet the fruits of 1987 have rotted with time's passage, as all of these institutions and systems now fail to fulfill their original roles. The spirit of that age and the democratic values for which the people spilt their blood have only grown fainter.

Twenty years after direct elections, The Hankyoreh decided it appropriate on this occasion to pursue the story of members of the 386 Generation. Let us reaffirm ourselves to the spirit of 1987 by reflecting on the past and by listening to their voices.

Currently department chief at LIG Fire Insurance, Choi Seong-yeol's freshman year of college in 1987 was spent more on the streets than within the classroom. Yet at present, he is just like any other person, preoccupied with his work and intent on providing his children with a good education.

Twenty years ago, Choi Seong-yeol was a naive freshman. As the stench of tear gas replaced the familiar smell of springtime, he began to turn his gaze toward the world outside the school gates. As the truth of the May 1980 Gwangju massacre came slowly to light through underground information sources - the press was still muzzled - Choi soon discovered a deep rage within him.

His life was turned upside down before the final exams of that year, when fellow student Lee Han-yeol was hit with a tear gas canister and died soon thereafter. Choi stood guard with other demonstrators in the halls of Severance Hospital to prevent the police from removing Lee's body that day, as activists suspected that the police might try to take the body in order to manipulate forensic evidence to make the cause of death unclear. Choi then accompanied the funerary procession transporting the fallen student to City Hall in an act of protest.

At the time, a stray thought came to mind. If he could but make one wish, he thought, it would be to broadcast the truth of the 1980 Gwangju massacre over the airwaves.

In 1991, after fulfilling his military service, he returned to student life, only to see Gang Gyeong-dae and Kim Gwi-jeong die during a demonstrantion in the same fashion as had Lee. Choi joined with his fellow students once more in protest.

But before long, he had become a senior. Many of his friends were preparing to disguise their educational background and enter the workforce as blue-collar employees in order to propel the nascent labor union movement. After much deliberation, however, Choi decided not to follow this path, casting his resume into the job market instead, following the path of the average students.

He chose a white-collar workplace, but one with a strong labor union. It was, in the end, his small way of trying to stay true to his values. It did not prevent him from having to endure the criticism of other students for being a "traitor."

Now, Choi departs for work every morning at 7:40, and his arrival home varies depending on the workload and the social plans of his colleagues. He will turn 40 this year, and his daughter will enter elementary school.

Married in 1996, he purchased a house in 2004 for 300 million won (US$318,000). He has since watched its value climb to 450 million won. Not that this thrills him. After all, as he has to continue living there, he is not about to put it on the market. He spends 700,000 to 800,000 won every month on his daughter's extracurricular educational fees, such as private institutes and tutoring, not an exorbitant figure in South Korea today. "My wife has joined with other mothers in the community in her frantic quest to improve our daughter's education," he confided.

At the workplace, he feels that the junior employees differ from him and his generation. They are young, but already have impressive resumes. Their culture of leisure is also different. Though in the past, employees would take every opportunity to go out drinking, the new recruits tend to be "busy," augmenting their proficiency by attending various evening academies. In addition, whereas Choi says his generation judges politics in terms of right and wrong, younger employees speak in terms of likes and dislikes.

Choi has become just another boring dad, a "geezer" tired of his job. He is an average "Joe" who has taken up rank among the Parks, Kims and Lees of this world.

What happened to the youthful Choi Seong-yeol, the Choi Seong-yeol who sought his schooling on the politicized city streets rather than in the classroom? Just as he had promised his college friends before graduation, he fearlessly participated in union activities from his first days as an employee in training. He began in the union's song brigade, and worked his way up to being a vice chairman of the union. The 1997-98 financial crisis was another turning point in his life. Amidst a storm of forced early retirements compensated for by consolatory bonuses, Choi somehow scraped by and survived the storm. Though he did his best on behalf of the union members, some 200 workers lost their jobs.

Of the 12 friends he has kept in touch with since graduation, five lost their jobs in the runup to and aftermath of the 1997-98 financial crisis. Other friends have cut off all contact.

Though he hung his hopes on the Kim Dae-jung government, they were soon replaced by disenchantment after he watched the president's method of dealing with the sit-in at the Lotte Hotel in 2000, in which the government ordered the police to enter the building and clamp down on the strike. His disillusionment with the Roh administration followed a similar pattern. "Both governments were the same as their predecessors, consistently resorting to violence against the workers," he said.

And thus the chain of frustrations has stretched on. "After our one victory in 1987," he lamented, "we have suffered nothing but successive defeats."

Choi is still undecided on whom to support in this year's presidential elections. Though his hands are full with work, he has not forsaken his interest in politics. After all, that is the least he can do to carry on the spirit of 1987. His support for the Democratic Labor Party (DLP) similarly springs from the pledges he made in his university days.

However, while he consoles his political identity by supporting the DLP, he does not believe they will arise as a viable alternative. In fact, he does not believe that politics can fundamentally change the world. He gave up that thought over the course of 20 years of frustrations, 20 years of setbacks, and 20 years of defeats. Now, the only hopes he clings to are the nebulous ones.

Perhaps it is time that wore him down. Then again, perhaps it is he who has adapted to the era.

Reporter Lee Jeong-hun

Translated by Daniel Rakove

Please direct questions or comments to [englishhani@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0422/1717137715201877.jpg) [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far![[Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0422/1517137717613239.jpg) [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

[Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

Most viewed articles

- 1Korean government’s compromise plan for medical reform swiftly rejected by doctors

- 2[Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- 3[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 4Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 5[Reporter’s notebook] Did playing favorites with US, Japan fail to earn Yoon a G7 summit invite?

- 6[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 7Korea protests Japanese PM’s offering at war-linked Yasukuni Shrine

- 8All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 9[Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- 10What Israel’s ‘warning shot’ response to Iran means for Middle East tensions