hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[News analysis] South Korea coming to confront Vietnam War civilian massacres

It was in July that Ku Su-jeong, 50, received a phone call from the police. They told her that she was being sued for “defamation through the publication of false information.” On Aug. 23, Ku appeared before the police and was questioned for three hours.

“I got the feeling that the police officer questioning me didn‘t know much about the issue. It was hard to even answer their questions because I couldn’t figure out what they were getting at. Of course, I guess you’d have to know the whole historical background to do a proper investigation, so it probably wouldn’t be easy for anyone,” Ku said.

“I was taken aback because they seemed more interested in what I thought about the plaintiff‘s claim that what I said was false than in verifying that what I said was true.”

Ku is the director of Amap, a social venture that arranges fair trade and fair travel between South Korea and Vietnam, and she is also a member of the board of the South Korea-Vietnam Peace Foundation, which was launched in September. Her job and title may change in the future, but the one thing that won’t change is that she was the first person to bring the civilian massacres carried out by South Korean troops during the Vietnam War to the attention of the country through articles published in the Hankyoreh 21 weekly magazine in 1999, while she was studying in Vietnam.

She had spent 17 years learning the truth and spreading the word through print articles, oral recordings and press interviews when she unexpectedly came face to face with the law. The meeting was unpleasant, to say the least.

Vietnam Veterans Association sues Ku Su-jeong for defamation

It was in May that Jang Ui-seong, 72, head of the welfare department of the Vietnam Veterans’ Association of Korea (VVAK), received a call from the police. Shortly after the launch of a preparatory committee for the South Korea-Vietnam Peace Foundation and the unveiling of the “Vietnam Pieta” statue on Apr. 27, VVAK organized a series of meetings of the heads of chapters in various cities and provinces to discuss how to respond to “Ku Su-jeong and other slanderers.” They appealed to South Korea’s president, prime minister, Defense Ministry and Foreign Ministry to take action. Soon afterward, the police asked the group if they wanted to take legal action.

Jang was chosen to represent 831 plaintiffs. “They were spreading all these falsehoods, but we don’t even use the Internet and couldn’t do anything about it, and they kept getting worse and worse as time went by. Abe is having a hard time because of the comfort women statue, and I guess he deserves it because of what Japan did, but what women did we violate to earn this Pieta statue?” Jang said, referring to Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

“When we were still an unofficial organization, our hands were tied, but since we acquired legal status three years ago, we gained the ability to file a lawsuit. We‘re going to take this opportunity to keep them from doing this kind of thing again,” he said. Seventeen years after Jang first came across Ku’s article, he has finally encountered the law - and now he‘s spoiling for a fight.

VVAK claims that there was false information in an interview with Japanese weekly the Shukan Bunshun in 2014, in a video that contained Ku’s remarks from the “peace pilgrimage” to Vietnam and in an interview that ran in the Hankyoreh this year. But the files that VVAK submitted contain virtually everything that Ku has done since 1999.

“The police questioned me at the greatest length about the interview with the Shukan Bunshun,” Ku recalled. During this interview, Ku made one remark about South Korean soldiers sexually assaulting Vietnamese women. There is a telling connection between the fact that the first thing VVAK took issue with was this interview and the fact that Jang repeatedly referred to “Abe,” “sexual assault” and the “Pieta statue.”

Apt comparison between Vietnam massacres and comfort women cases

This was the first year that the issue of the civilian massacres during the Vietnamese War and the issue of the comfort women for the Japanese Imperial Army began to merge into the same discourse. The agreement about the comfort women that was reached by the South Korean and Japanese governments on Dec. 28, 2015, acted as the catalyst for this combination.

The same artist couple who made the comfort woman statue in front of the Japanese embassy in Seoul (the controversial statue that the Japanese government wants removed) also made the Vietnam Pieta statue, which is designed to push the South Korean government to apologize for the civilian massacres by ROK forces during the Vietnam War. This statue symbolizes the fact that South Korea‘s early modern and contemporary history cannot be told as a narrative of continuous victimhood. This reflects the paradox that the issue of the comfort women cannot be resolved until South Korea acknowledges that it was an aggressor during the Vietnamese War.

The key factor in “defamation through the publication of false information” is the veracity of the information that the defendant published. The evidence that VVAK has submitted to demonstrate the falsehood of Ku’s claims is reportedly a statement by South Korea’s Defense Ministry that South Korean troops did not carry out any civilian massacres during the Vietnam War.

This is the position that the Defense Ministry has always maintained. It has never listened to the testimony of the alleged victims, nor has it ever carried out a field investigation. The South Korean government’s attitude resembles the logic of the Abe administration in Japan, which consistently denies the compulsory mobilization of the comfort women on the grounds that there is no corroborating evidence.

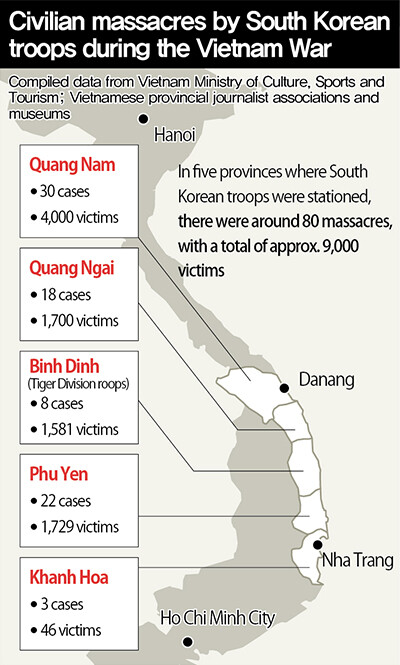

More than 9,000 Vietnamese civilians were killed by South Korean troops

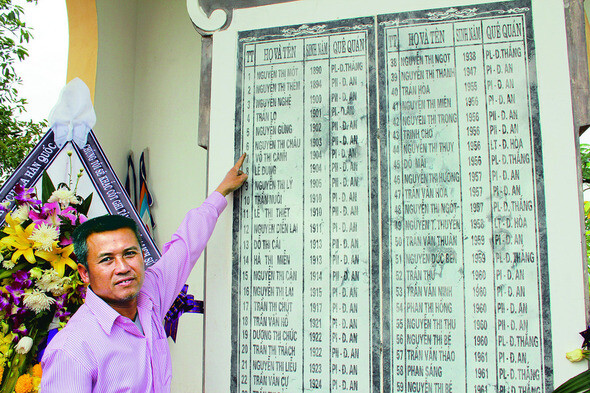

Ku’s claims, on the other hand, are supported by interviews with Vietnamese locals, by documentation from several investigations by the Vietnamese government, by about 60 memorials to the victims that have been erected in areas where South Korean troops were stationed and by three remaining “memorials of hatred to South Korean troops.” So far, Ku has compiled 33 different official documents, including several American documents, including reports by inspectors with the US military command in Vietnam from 1968 to 1970. It is estimated that more than 9,000 Vietnamese civilians were killed by South Korean troops in these massacres. More people keep coming forward to testify of sexual assault by South Korean soldiers.

But veterans’ organizations claim that all these things are falsehoods and forgeries. They do not even recognize the testimonies of massacres by some South Korean veterans, their own comrades-at-arms. Veterans‘ organizations blocked an event that was supposed to be held at Jogyesa Temple in Seoul on Apr. 7, 2015, which victims of the civilian massacres during the Vietnam War were planning to attend.

Veterans have dismissed all the victims - regardless of age and gender - as having been “Viet Cong disguised as civilians.” For the veterans, the Viet Cong were enemies who needed to be killed. They claim that no sexual violence occurred and that it was the Viet Cong who lopped off the breasts of female victims.

Lim Jae-seong, 36, met the law before he became a lawyer. Before he began his career, he stood trial for conscientious objection to military service and served a prison sentence. For Lim, who attended university in the 2000s, the Vietnam War was one more unforgettable example of violence by the state and one more reason not to serve in the military, just like the suppression of a revolt on Jeju Island in 1948 and the Gwangju Massacre in 1980.

Lim is part of the Asian human rights team with MINBYUN-Lawyers for a Democratic Society, which visited Vietnam in July 2015 and set up a Vietnam War research group with MINBYUN early this year. Lim got to know Ku while serving as a leader of this research group, and he also served as a member of the board of the South Korea-Vietnam Peace Foundation. In July, he got a call from Ku, who had just had her first encounter with the law.

The research team for the Vietnam War was inspired by the realization that there has been no official investigation, apology or compensation for the civilian massacres carried out by South Korean troops during the Vietnam War, even though it is a well-known fact that these massacres occurred. After carrying out a legal review of the issue, the research team devised a plan to push for the enactment of special legislation to investigate and to enable Vietnamese victims to sue the South Korean government for compensation.

An opportunity to find the truth in court

“To do so, there first needs to be judicial confirmation of the civilian massacres, but that was such a huge task that we hadn’t been able to find the right opportunity. But then the veterans‘ groups created this opportunity for us,” Lim said.

The four attorneys Jang Wan-ik, Kim Man-ju, Park Jin-seok and Lim Jae-seong agreed to defend Ku and filed the necessary documents with the court. They brought on more attorneys, increasing the legal team to 10 people. The legal team will soon be submitting legal briefs to the police containing a variety of documentary evidence and interview transcripts.

But that’s just the beginning. The legal team is also planning to have the findings of official investigations by the Vietnamese government translated into Korean and to carry out an on-site investigation in Vietnam next year. Once they have compiled these documents, they will also have to carry out a legal analysis of the facts. They can‘t afford to be sloppy or negligent about a single thing.

“Our first priority is establishing with certainty that the massacres occurred, but as we make our preparations, we are thinking ahead and bearing in mind the special legislation we’ll need to enact and the damages lawsuit we‘ll need to file. We hope that this lawsuit will greatly increase social interest in the civilian victims in Vietnam, which will lay the groundwork for our future activities,” Lim said.

Legal team preparing through document translation, site inspections

These days, Ku Su-jeong is organizing “tours for peace” with South Korean students around Vietnam. It is an arduous journey that lasts for more than a month.

“What I’ve done so far is spread the word about the actions of the Korean troops based on the testimony of the victims. If I stand on trial, we‘ll need to put the puzzle pieces together by looking in detail at all the troop movements. That will be a new beginning for me. It’s true that I’ve been sued, but I actually think that’s a good thing,” Ku said.

The Vietnamese government has never officially addressed civilian massacres by South Korean troops. This is partly a result of the historical view that the South Korean troops who fought in the Vietnam War were not there in an official capacity but rather as mercenaries for the Americans. But there‘s a practical reason, as well: South Korea invests more in Vietnam than any other country. But signs of a starkly different approach have started to appear in Vietnam this year, with leading newspapers providing extensive coverage of this issue.

The comfort women issue did not start being discussed publicly in South Korean society until former comfort women Kim Hak-sun made her first testimony in Aug. 1991. But more than 25 years later, Japan still refuses to officially acknowledge the “compulsory mobilization” of the comfort women, and it has taken no judicial action. The former comfort women are now being ignored even by the South Korean government.

Until South Korean society clearly acknowledges the identity of the aggressors in Vietnam, not only Vietnamese victims but also South Korean victims cannot be freed from their suffering. The scope of that suffering includes more than 5,000 people who lost their lives in Vietnam, more than 10,000 who were injured and more than 20,000 who are still affected by exposure to Agent Orange. The South Korean judiciary now has a chance to address these historical wrongdoings.

By Ahn Young-choon, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 4US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 5[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 6[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 7Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 8All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 9More South Koreans, particularly the young, are leaving their religions

- 10John Linton, descendant of US missionaries and naturalized Korean citizen, to lead PPP’s reform effo