hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special reportage part II] Peaceful rest for a victim of massacre in Vietnam

By Ku Su-jeong, special contributor to Hankyoreh 21 magazine in Vietnam

The memorial stone erected in Ha My in 2000 by the Korean Vietnam Veterans’ Welfare Association bears no inscription. Actually, that isn’t entirely true - there was originally a memorial inscription on the back of it. It read, “May the sand dune and the trees that now grow upon it now remember the history of slaughter.”

The South Korean government and the Veterans’ Association took issue with it and went to work demanding its revision, using a mixture of cajoling and pressure tactics. Surviving family members and villages adamantly refused. “This is our history, our past, our truth,” they said. But they ultimately bowed under pressure from the Vietnamese central government.

The villagers vowed not to change a single word. Instead, they covered over the text with a large piece of marble with lotuses painted on it - in the hope that one day they might be able to remove it. The villagers remembered the Ha My massacre as having been “killed twice,” and the second massacre may well have been the attempt to blot out even the memorial inscription. As the truth was buried once again, it was not a new life that grew in the hearts of the villagers, but a new wound.

A decade later, in March 2012, the villagers’ committee presented the South Korean visitors at the Ha My memorial ceremony with a printed version of the original inscription. This act reflected the villagers’ hopes that the truth might once again come to light. Reading it, we froze on the spot. Everything seemed to go black. We couldn’t fathom it - how long would be have to bear the karma from it? Did Phamtihoa know? Is that why she showed such concern for us until that very final moment? Was she worried we would be hurt again when we saw it?

At last, Phamtihoa’s coffin was lowered. Her eldest son, the chief mourner, who could not see ahead of him, folded dirt in her skirt and cast three fumbling handfuls of it over the coffin. The sound of the earth falling seemed as loud in my ears as a tower crashing to the ground. Villagers picked flowers from the wreaths and began strewing them over Phamtihoa’s coffin. One of them put a bunch of yellow chrysanthemum petals in my hand.

“May all her earthly suffering be given to us, so that her soul may take flight like the wings of the butterfly. May she walk again on healthy legs in a place without war or suffering.” The petals fluttered through the windless air before settling atop the lid like snow. The villagers tied up the now-sparse wreaths with funeral ribbons, the messages facing outwards, and laid the ribbons neatly on the coffin, as though wrapping a package.

“We are in agony, grief-stricken, and so very sorry. May you rest in peace,” read one message from Gotjawal School in Jeju. “Our sincerest condolences,” read another from the Association of Citizens Thinking of Vietnam and Korea. As I took one last look at the messages before leaving the cemetery, it felt like my own private ceremony, a reverent farewell to Phamtihoa.

After the burial ceremony, I went to see the Ha My memorial statue. I wanted to be alone, if only for a moment.

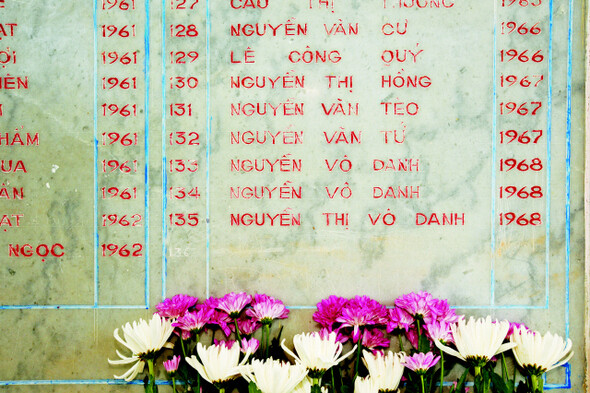

#82 Nguyen Van Phan 1959

#114 Nguyen Thi Xi 1963

I had passed there many times, but I had never seen the names of Phamtihoa’s children. Suddenly, there they were, leaping out at me. Nguyen Van Phan was born in 1959 - he was her 10-year-old son. Nguyen Thi Xi was her five-year-old daughter, born in 1963.

#130 Nguyen Thi Hong 1967

#131 Nguyen Van Teo 1967

#132 Nguyen Van Tu

These three children had been born in 1967. They were two-year-olds, still called by their childhood names. They had been too young to receive their official names.

#133 Nguyen Vo Danh 1968

#134 Nguyen Vo Danh 1968

#135 Nguyen Thi Vo Danh 1968

These children had all been born in 1968, the year of the massacre. The name given was “Vo Danh” - the equivalent of “no name,” or “John Doe.” They had been newborns. There hadn’t been time to name them. Nguyen was the family name. The “Thi” in the third name meant that the baby was a girl. So the name at the farthest right end of the stone was that of a newborn girl who had not received a name. The numbers at the front - 82, 114, 130, 131, 132 - appeared to be serial numbers. The statue was covered with 135 names of people who lost their lives that day, from an elderly woman born in 1880 to nameless babies born in 1968.

I had not cried during the funeral ceremony, but now, standing before the Ha My memorial, I felt the tears well up. Seeing the names of innocent children who had not yet had time or chance to commit any misdeed, I crumbled to the ground and lay face-down, wracked by feelings of guilt. Phamtihoa had died unexpectedly, leaving only the final gift of forgiveness, but I had no memory of letting her go. All I could feel was her still-living hand against my back and her voice saying, “You’ve got a long trip ahead. Get along now!”

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong? [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/8517133419684774.jpg) [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?![[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/6817133413968321.jpg) [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

Most viewed articles

- 1‘Right direction’: After judgment day from voters, Yoon shrugs off calls for change

- 2[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- 3Strong dollar isn’t all that’s pushing won exchange rate into to 1,400 range

- 4Where Sewol sank 10 years ago, a sea of tears as parents mourn lost children

- 5Japan officially says compensation of Korean forced laborers isn’t its responsibility

- 6[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- 7[News analysis] Watershed augmentation of US-Japan alliance to put Korea’s diplomacy to the test

- 8Korea ranks among 10 countries going backward on coal power, report shows

- 9Faith in the power of memory: Why these teens carry yellow ribbons for Sewol

- 10[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces