hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special reportage- part I] Attending the funeral of the victim of a South Korean war crime in Vietnam

By Ku Su-jeong, contributing writer to Hankyoreh 21, in Vietnam

The chanting of the monks, prayers for the old woman Pamtihoa to have a peaceful journey to the next life, can be heard at the entrance to the village. My heart sinks, and I find it hard to move forward, as if my feet are glued to the ground.

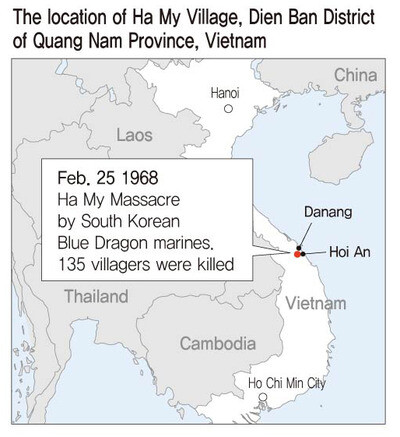

“She’s here! She’s here!” Several people from Ha My village in Dien Ban District of Quang Nam Province, Vietnam who had been squatting in a narrow alley, come running out and pull me along by the hand.

“When I go, I will carry away all the burden of the past”They nod at me, as warm as if one of their own people had returned from afar. The wreaths of flowers that various Korean organizations had sent to express their condolences line the funeral home, which is full of commotion.

I light three sticks of incense and place them on the funeral home’s altar and then bow twice. Smoke rises from the incense like the woman’s last breath. Behind is a portrait of the deceased. In the picture, Pamtihoa is silent, just as she always was.

When I emerge from inside the mortuary, I see Jjeungtitu, another old woman who survived the massacre at Ha My. She hobbles around on her stump leg that ends at her ankle, bowing her head low as she savors the scent of each wreath. She repeats each of the Chinese characters on the messages of condolence again and again. “Now, may you rest in peace in heaven, where there is no war.” “The love that you planted in our hearts will bloom as peace.”

That morning, Pamtihoa’s face had been glowing as it had not for a long time. Her eldest son, who had been in and out of the hospital since the past winter as he received five rounds of surgery, had returned home, and her second son whom she had missed so much had flown all the way from Australia. Afraid that she might outlive her son, she had abstained from all food and drink and had refused to say a word. But now, sitting with her two sons, reunited after dozens of years, she spoke carefully and at length.

“When I go, I will carry away all the burden of the past,” she said. “So even after I’m gone, you need to take good care of our Korean friends when they visit. Tell the people of the village that they should stop hating them now, too. I feel so sorry for them… They came all the way from Korea for the memorial service. I can die without any regrets. I was more opposed to the idea of covering the epitaph on the memorial stone than anyone else, but 10 years have passed now and what can be done about it now? When I think of Koreans coming all the way here and getting their feelings hurt, I also think it might be better just leaving it as it is…”

They didn’t know that that would be the old woman’s last request. While she had been having trouble keeping down two spoonfuls of porridge a day, on that day she finished off an entire bowl of gruel that her son fed her. “You’re all hungry, too. Go and eat something,” she said.

Just when the family members sat down at the table to eat, they heard the sound of someone pounding the bed. They rushed over and found the old woman gasping out her final breaths. At 12:40 AM on June 16th, Pamtihoa departed from this troubled world at the age of 87. She looked to be at peace, as if she had drifted off to sleep. She was truly at rest for the first time in her life.

The riddle that Pamtihoa left behind her, unable to solve until the end, is why sweet, friendly Korean boys suddenly devolved into bloodthirsty, murderous monsters on that fateful day in 1968.

In March 1965, the 3rd US Marine amphibious force landed in Da Nang, Vietnam. Moving south, the marines seized Ho Ah Bang and Di En Ban, and in spring of 1966 they took hold of the old French base of Con Ninh at Ha My Beach.

US forces swiftly began to pacify the surrounding villages, and the people of Ha My were relocated to the refugee camp at Hoi An called a “strategic hamlet” and to the slums of Da Nang. After that, in Dec. 1967, the 5th regiment of the US Marine Corps handed the base at Con Ninh over to the Blue Dragons, the ROK 2nd marine brigade.

The people of Ha My could not endure life at the refugee camp for long. There wasn’t enough food there, and it was extremely crowded. As the young, the sick, and the weak began to die from dysentery and other infectious diseases that spread amid the squalor and unsanitary conditions at the camp, the village elders submitted a petition to the government of South Vietnam and the commander of the South Korean forces to allow them to return to their village. It is not certain whether they were in fact given permission. But in any case, the people of Ha My went back to their village in Dec. 1967.

South Korean soldiers who were based atop a sand dune at Ha My Beach at the time provided food and building supplies to the village people as they tried to reestablish themselves. The villagers returned the favor by giving the soldiers presents of green peppers and other local delicacies.

The massacre took place about one month later, on Feb. 25, 1968. For this reason, the people of Ha My find it hard to believe that the unit that attacked their village was the same unit that had helped them before the massacre. They believe that the unit had been replaced immediately before the massacre, or at least that the soldiers from that unit did not directly participate in the massacre.

When I visited Ha My village for the first time in 1999, an old woman beat her breast with grief, saying that she just could not understand why the South Korean soldiers suddenly committed the massacre. “When you go to Korea, can you please ask the high officials why they shot innocent civilians such as ourselves? Ask them why they had to kill all of the newborn children…” For the survivors at Ha My, the massacre on that day remains an unsolved riddle of history.

“Don’t you dare say that I was lucky”

It was 9:30 in the morning on Feb. 25 of 1968, year of the monkey, and the twenty-fourth day of the first month of the lunar calendar. The South Korean marines positioned their tanks and armored vehicles at the entrance to Xom Tay, a tiny village that was part of Ha My, and started advancing into the village from three directions. Around 10am, the soldiers gathered the villagers at three different locations, one of these being the house of the Nguyen family.

According to the survivors, what followed next was a long and verbose speech by the commander. Some soldiers were even handing out candy to the children. The Ha My villagers thought that the South Korean soldiers had gathered them together to hand out food. The soldiers didn’t seem to have any heavy weaponry. The villagers waited patiently through the boring speech, wondering what the soldiers were going to hand out today.

Pamtihoa told the people beside her about a dream she had had the previous night. “Last night, I dreamt that I was putting a chicken egg or a duck egg by the bedside of someone who had died and holding a ceremony for them. I have a bad feeling about today,” she said.

But no one believed her. “Don’t say that kind of thing, or it might come true,” they chided her. “Nothing is going to happen.”

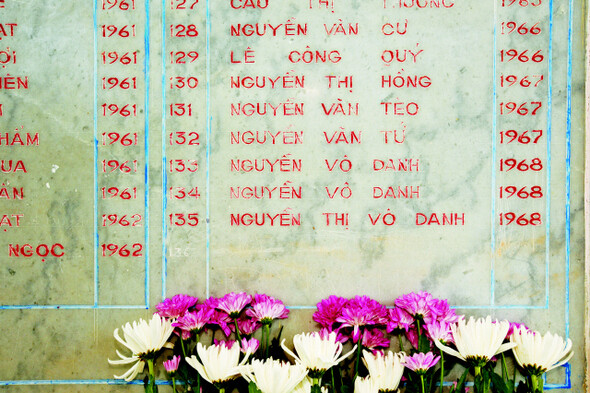

Once he concluded the speech, the commander turned his back on the villagers and started walking away. He had gone a few steps when he made a gesture with his hand. At the signal, M60 machine guns and grenade launchers that had been hidden in the woods opened fire. It only took two hours to raze the village to the ground, slaughtering 135 villagers from 30 families and setting all the houses on fire.

When Pamtihoa saw the grenades flying toward her, she dove to the ground, covering the bodies of several children underneath her. The first grenade bounced off her back, but the second one exploded under her feet. Her field of vision went completely white, and she lost consciousness.

After the massacre was over, a few survivors wrapped up the bodies of the dead in straw mats brought by people from neighboring villages, buried them in a shallow holes they had dug, and marked the spot with little stones and sticks.

But the next day, South Korean soldiers came back to the village with two D-7 bulldozers. They dug up the shallow graves and crushed the bodies that had not yet been buried. Even today, the people of the village say that they were “killed two times.” They recall the desecration of the bodies and the graves as the most inhumane act perpetrated by the South Korean soldiers.

Documents in Vietnam record the horrific scene in the village after the massacre: “A line of people were using wooden chopsticks to pick up the scattered bone fragments and pieces of flesh and place them in large bamboo baskets.”

Pamtihoa lost her five-year-old daughter and ten-year-old son in the massacre. Her cousin's wife, who had lived with her before, also died, as did the child she was carrying in her womb, another baby who was still nursing, and a third who had just started walking. Pamtihoa herself was severely injured by a grenade, losing both feet. The cousin's wife was nine months pregnant. After her rape and death at the heads of the South Korean Army, Pamtihoa said, her belly split open, and the baby hung out, along with her entrails. Pamtihoa’s two oldest sons were elsewhere and escaped the slaughter: 14-year-old Lap was in Da Nang working on a farm, while 11-year-old Thinh was helping on another family farm in Hoi An.

The family's misfortunes continued. After the war was over, Lap returned home and was recultivating the abandoned, overgrown land when an unexploded shell went off and took both his eyes. Thinh, fed up with the poverty, became one of the country's boat people, leaving his homeland and family behind for good.

I recall using the term "lucky survivors" in a previous piece somewhere. Pamtihoa, one of those survivors, would shake her head at the use of the term. "I merely got out of there with my life," she would say. "It's like being a walking corpse." Still, she needed to keep going, which required her to beg. Her family members said it tore them apart to think of what she went through at the time. Clutching her funeral portrait, one shouted, "Don't talk to us about how lucky she was!"

According to the villagers, the South Korean forces ran over the bodies and graves with a bulldozer, then razed Ha My to the ground, leaving not a single blade of grass behind. Soldiers began transporting the wounded to their bivouac and other sites.

People with their brains leaking through bullet holes in their heads, people whose entrails were hanging out of the stomachs, people who had lost limbs to grenades, people with burns all over their bodies, the stench of rotting flesh. The scene was chaos - "like a leper colony," Pamtihoa said. There was no medicine, let alone doctors; no one was treated. Pham's own wounds were soon ridden with maggots, which writhed their way up to her chest. But what tormented her the most were the moans of her young daughter, whose body was covered in gunshot wounds, shrapnel, and burns.

It was a whole week later, on March 2, that the wounded were sent from the makeshift barracks to a German medical ship docked in Da Nang, Pamtihoa recalled. Once she reached the hospital on the sea, she was taken straight to the operating room to have her legs amputated. Her daughter went into intensive care. Body sagging, the little girl peered around with fear-stricken eyes and clutched the folds of her mother's dress in her tiny hand. "Mom, please don't leave me," she cried. When she came to, Pamtihoa pulled her legless body around the floor of the hospital, clutching any leg she found and begging its owner to help her find her daughter. Grisly rumors went around the hospital that dead Vietnamese were being tossed into the sea. She didn't believe it - she was certain they could not be so inhumane as to throw a human being to be devoured by starving schools of fish. She kept pleading for help. Finally, a Vietnamese nurse took her to her hospital bed and told her the news: her child was dead and had been taken to a mortuary at a general hospital in Da Nang. At the hospital, bodies not claimed after one day were recorded as having no relatives and subject to burial by the administrative office. Hearing from their mother about their sister's death, Lap and Thinh went to look for the body but were unable to locate it.

A four-day funeral: 'Will there be any Korean mourners?'

The survivors of the massacre were survivors in name only. They had lost their families, their homes, condemned to years of wandering like living phantoms. Pamtihoa’s family survived by living off another struggling family, ever conscious of the obvious burden they were causing. In Da Nang, Lap grilled French bread for US soldiers to eat. The legless Pamtihoa begged all day, struggling from one US base to another. She didn't hesitate to take money from the "Dai Han" who had made her the way she was, either - but she always counted it separately. She would spread it out before her brothers and spit, "Look at the money I begged off the Dai Han!" Lap's memory is forever etched with the image of his mother muttering the names of all her dead relatives as she fanned the bills with her hand and counted them one by one: "That's for my sister's life cost, that's for my little brother's life, that's for my aunt's life. . . ."

Her funeral lasted four days. Vietnamese funerals are typically three-day affairs, but after consulting with her family, the People's Committee and Ha My Surviving Family Members' Association decided to extend it one day. They didn't know if any mourners might be traveling in from South Korea.

Unfamiliar with Vietnamese funeral practices, I was unsure how I should offer proper condolences and console the survivors. The family members and local residents all showed great consideration to me as a foreign mourner, and their extremely kind treatment only made me feel more awkward. Still, I wanted to remain by her side a bit longer, if only for another evening. The coffin was to be carried out the next day, so I stayed up all night with the villagers and watched over the memorial.

There was none of the drinking that you typically see at a Korean funeral hall, and no one was playing cards - a common practice in Vietnam. Everyone stuck together late into the night, sitting around and talking about the deceased. Every so often, while conversing or just briefly resting their weary bodies on the bench, someone would make sure to run over to the altar and light incense to pray for her eternal rest. The sticks burned brightly in the blackest of night, glowing a fiercer red as the wind blew. All night long, they cast their glow on her portrait.

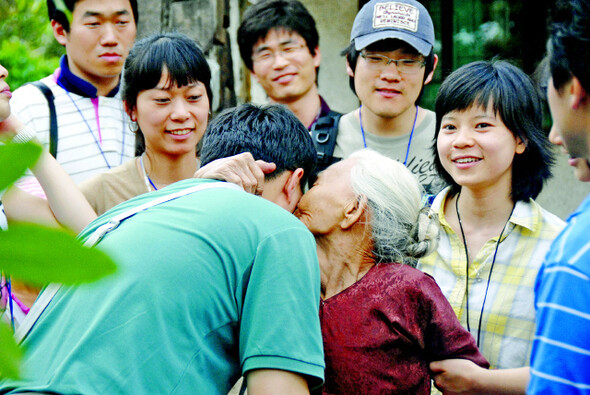

Pamtihoa had welcomed a stranger from the same land as the soldiers who took her life. She had held my hands warmly to say that there must never be a war like that again, that people should not have to live as she had. She would also tell her grandchildren to pick coconuts for us, or give us expensive tea, a gift from Japan that she kept hidden away. When I felt so mortified that I burst into tears, she cried too and said, "What are innocent young people like you doing here? Come now. You poor things." She embraced each departing guest in turn, kissing them on the cheek and patting them on the back. "Goodbye now," she said. She worried about the long trip ahead, but was unable to leave the house herself, so she simply stood there on her hobbled legs and watched us until we disappeared down the alley.

In March 2012, a 45-year memorial was held for the Ha My massacre. It was the first time Koreans had attended. A grim feeling hovered over me while I was there. Pamtihoa, one of the Ha My "survivors," might die the very next day, and I could not leave the family to say goodbye to her forever, or let her go to her grave bearing the anguish of living all those years without her legs. A year before, in January 2012, a group of visitors had come to Ha My as a delegation from the Peace Museum on Jeju Island, and a tearful Pamtihoa had told them: dozens of memorials had been held by the villagers over the years, and not once had a Korean come. Please, she said, come and console those 135 spirits that were so unjustly sacrificed. When we finally went, we were met by a profound sadness that lingered over Ha My even now, 45 years later. During the ceremony, we didn't speak a word. We wanted to turn our heads, shut our ears. If there had been a hole to hide in, we would have. It was there, in Ha My, that I finally recognized what a luxury it is to be able to talk about truth, forgiveness, reconciliation.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 4‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 5[Reportage] On US campuses, student risk arrest as they call for divestment from Israel

- 6[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 7Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 8[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 9Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 10[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father