hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

TV producer’s suicide causes troubled industry to reflect

By Kim Yang-hee, staff reporter

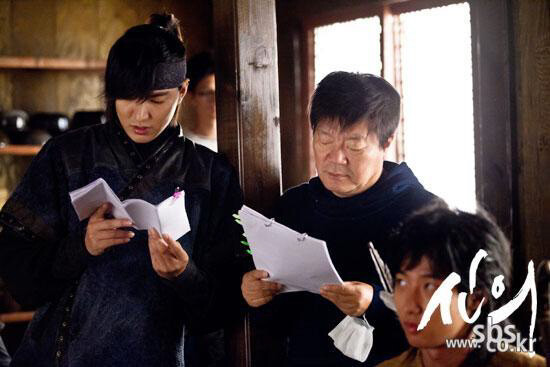

After celebrated television producer Kim Jong-hak took his own life on July 23, the world of Korean broadcasting has been echoing with criticism of the system of outsourcing the production of TV dramas, and the tricky tightrope that these subcontractors must walk along.

It has been acknowledged that Kim’s suicide cannot be blamed entirely on structural problems in the industry, since he had run into trouble when his large-scale and expensive dramas “The Legend” and “Faith” flopped.

But the general view is that the problematic aspects of outsourced production must be corrected, as these can lead to various side effects such as actors not getting paid when a production goes bust.

This article explores the reality of production outsourcing.

■ More than 60% of network TV dramas are outsourced

The only TV dramas being shown on the major Korean networks that were actually produced by the networks themselves are “Guam Heo Jun” and “Scandal: A Shocking and Wrongful Incident” on MBC, “Your Woman” and “Empire of Gold” on SBS, and “Sincerity Moves Heaven,” “Namchon,” “Eun Hee,” and “Drama Special 2013” on KBS.

Production was outsourced for 63.6% of the 22 TV dramas being broadcast over the course of a week.

The industry analysis is that nearly 75% of all TV dramas aired last year were produced by an outsourced production company.

There are 156 TV drama production companies registered with the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism (including some that have gone out of business).

Every day, the competition to win airtime grows fiercer, and only 34 of those companies made TV dramas that actually appeared on the airwaves in 2012.

■ On average, the broadcaster only covers 50% of the production costsWhen making a mini-series, production of each episode usually costs at least 250 million won (US$224,000).

Historical dramas cost even more. MBC is said to have poured 500 million won (US$448,000) into each episode of “Gu Family Book.”

The three major networks (SBS, MBC and KBS) on average cover about 50% of production costs. When the drama is a collaboration of top stars and popular writers, the networks sometimes pay even more as they compete for the right to broadcast the drama.

The outsourced production company must cover the remaining production costs through “sponsorship notices,” or the messages at the end of the drama indicating who sponsored it.

While the production company generally gets to keep 100% of sponsorship revenue, the broadcaster can take some of this when it exceeds a certain amount.

Revenue from product placement, where viewers name brand products are featured in a TV drama, is split half and half between the broadcaster and the production company.

Broadcasters keep all of the revenue from the commercials that run during the drama. If all of the ads are sold, the broadcaster can make around 300 to 400 million won per episode of a miniseries.

While the production company retains the rights for overseas licensing, typically a subsidiary of the broadcaster handles these sales and takes a 20% commission. And with the overseas interest in “Hallyu” (Korean wave) dramas on the wane recently, overseas licensing has not been easy.

“When broadcasters are calculating production costs, they factor in not only the sponsorship notices, but also the money that the production company could make from overseas licensing,” said Park Sang-ju, general manager at the Corea Drama Production Association (CODA). “The thing is that advertising from sponsorship notices is greatly affected by ratings, and revenue from overseas licensing is uncertain as well, since it is determined in the future.”

“Essentially, when a production company begins a working on a TV drama, it is 50% in the hole,” Park said.

The risk is even greater for large productions. If production companies have trouble licensing big-budget dramas overseas, they accrue a lot of debt.

In 2012, Kim tried to cover his production costs with a supplementary project based on “Faith.” But the ratings were not high, and there were also difficulties with attracting indirect advertising because it was a historical drama. As a result, the 10 billion won (US$8.96 million) production costs were probably a huge burden, some believe.

■ Casting top stars becomes more and more expensive

Thanks to the Hallyu craze, the money that top stars can command has gone through the roof, and the appearance of new TV channels owned by newspapers has pushed up the top stars’ fees even more.

A number of actors are paid about 100 million won (US$89,600) per episode. When Kim cast Bae Yong-jun in the drama “The Legend” in 2007, Bae received 250 million won per episode.

Since dramas are scheduled before they are produced, production companies are to some extent obligated to pay the fees demanded by the popular actors and writers that the broadcasters are looking for.

This is the reason that people sometimes say that broadcasters and production companies suffer when ratings are low, but popular actors and writers do just fine.

In Korean dramas, casting fees usually take up 55-65% of the total budget, compared to 20-30% in Japan and 10% in the US, sources say.

■ A public discussion is needed on more realistic production budgetsAnother issue with outsourcing production is the fact that broadcasters assign airtime to new, inexperienced production companies.

“When a former employee of a broadcaster starts their own production company, they are sometimes given airtime as a sign of appreciation for their work at the network. But the broadcaster doesn’t actually take responsibility for the project,” Park explained. “Sometimes situations occur where actors are not paid for their time.”

Park argues that only production companies that meet certain requirements ought to be allowed to produce dramas.

While the Ministry of Culture Sports and Tourism is working to implement a standardized contract dealing with how revenue should be divided between broadcasters and production companies, it is unlikely that this would be enforceable.

“The problems currently faced by drama production studios are rapidly getting worse, and no one is putting on the brakes,” a top executive at the drama department of one broadcaster said on condition of anonymity. “It’s possible to regard everyone in the industry as having some blame in Kim’s death.”

“We must all take a good look at ourselves. Broadcasters, production companies, and actors must all work toward a compromise on production fees, for the sake of the industry.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0416/8917132552387962.jpg) [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces![[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0416/8317132536568958.jpg) [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

- [Guest essay] At only 26, I’ve seen 4 wars in my home of Gaza

- [Column] Syngman Rhee’s bloody legacy in Jeju

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- 2Faith in the power of memory: Why these teens carry yellow ribbons for Sewol

- 3[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- 4[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- 5Korea ranks among 10 countries going backward on coal power, report shows

- 6Final search of Sewol hull complete, with 5 victims still missing

- 7[News analysis] Watershed augmentation of US-Japan alliance to put Korea’s diplomacy to the test

- 8How Samsung’s promises of cutting-edge tech won US semiconductor grants on par with TSMC

- 9K-pop a major contributor to boom in physical album sales worldwide, says IFPI analyst

- 10World famous Korean instant noodle: truth and misconceptions