hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

South Korea must choose energy future: dirty coal or renewable?

The efforts of other countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions has had the incidental result of reducing the price of coal, but South Korea should not assume that it will be able to exploit this indefinitely.

As the expression goes, the Stone Age did not end for lack of stones. The question now is whether we will be able to put down the burning stone that has dominated the fossil fuel age. In order to do so, we will have to leave the coal buried in the ground, like the fossil it is, and rush forward to the renewable energy age. While everyone points their finger at coal as a dirty energy source, in 2013, 41.3% of the world’s electricity was made by burning coal. Coal’s status as the world’s primary energy source is as solid as ever, but efforts to advance a future with renewable energy as the new title holder are formidable, as well.

At the end of May, at the G7 Summit in Japan, participating countries announced a commitment to ending fossil fuel subsidies by 2025. Throughout the entire process of fossil fuel production, from manufacturing to consumption, various kinds of subsidies serve to keep the price of fossil fuels and products that use fossil fuels low in order to promote their consumption. Coal was not specifically mentioned in the resolution, but coal is the most obvious target, as it is the source of 46% of the carbon dioxide emissions created by fuel consumption worldwide, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

As coal is the main contributor among fossil fuels to the greenhouse gas that is causing climate change, ending its use is considered a priority. Now that the countries that possess over 60% of the world’s economic power and hold the most clout within the international society have nailed down a deadline for the end of fossil fuel subsidies, it seems the global community, which was already moving away from coal, will hasten its steps in that direction.

The change is already apparent in the numbers. According to global energy company BP, as the demand for power grows in developing countries, worldwide commercial consumption of coal increased 22.7% from 2005 to 2015. However, OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) member countries, the majority of which have committed to decreasing greenhouse gas emissions, reduced commercial coal consumption by 16.7% over the same period. As it is impossible to reduce greenhouse gas while consuming mass amounts of coal, the reduction is inevitable.

The US, the number one producer of accumulated greenhouse gas emissions, is also expected to rapidly move away from coal. While President Obama’s Clean Power Plan placed restrictions on coal power, presumptive presidential candidate Hillary Clinton has pledged to source 33% of the country’s electricity from renewable energy sources by 2027, up from 13% in 2014. Up until 2005, 50% of the electricity generated in the US was sourced from coal. That figured dropped to 33% last year, thanks to the country’s large increase in natural gas power generation.

For China, the world’s biggest consumer of coal, cutting back on the fossil fuel is not just an issue of preventing climate change, but also a necessary step for solving the social issue of air pollution. In 2013, with the State Council’s announcement of a plan to prevent air pollution, the country resolved to place restrictions on increases in coal consumption while also working to develop renewable energy. The Renewables 2015 Global Status Report, prepared by REN21 (Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century), clearly indicated the result of these efforts, with China ranking highest in four categories, including scale of investment, solar energy generation facility capacity, wind energy generation facility capacity and total renewable energy generation facility capacity.

The UK’s efforts to move away from coal are especially striking. While the British Empire was built through an industrial revolution powered by coal, Britain is now pushing through a plan to stop using coal for the production of electricity completely, with all coal power plants set to be closed by 2025. According to media reports, for the first time since the first coal power plant began operating in London in the 19th century, Britain's coal power generation dropped to zero at several points last month. With that news in mind, the goal does not seem unachievable.

The world’s private sector is also busy working to put an end to coal power. A look at a website that tracks the current status of worldwide investment institutions’ divestment in coal-related businesses (http://gofossilfree.org) shows that, as of July 7, 544 funds, universities, foundations and other investment institutions, including the world’s largest pension fund, the sovereign wealth fund of Norway, are withdrawing investment from coal-related enterprises. The investment institutions manage funds worth approximately 3.4 trillion dollars.

S. Korea coal consumption rises to 5th place

On this front, South Korea is headed in the opposite direction from the rest of the world.

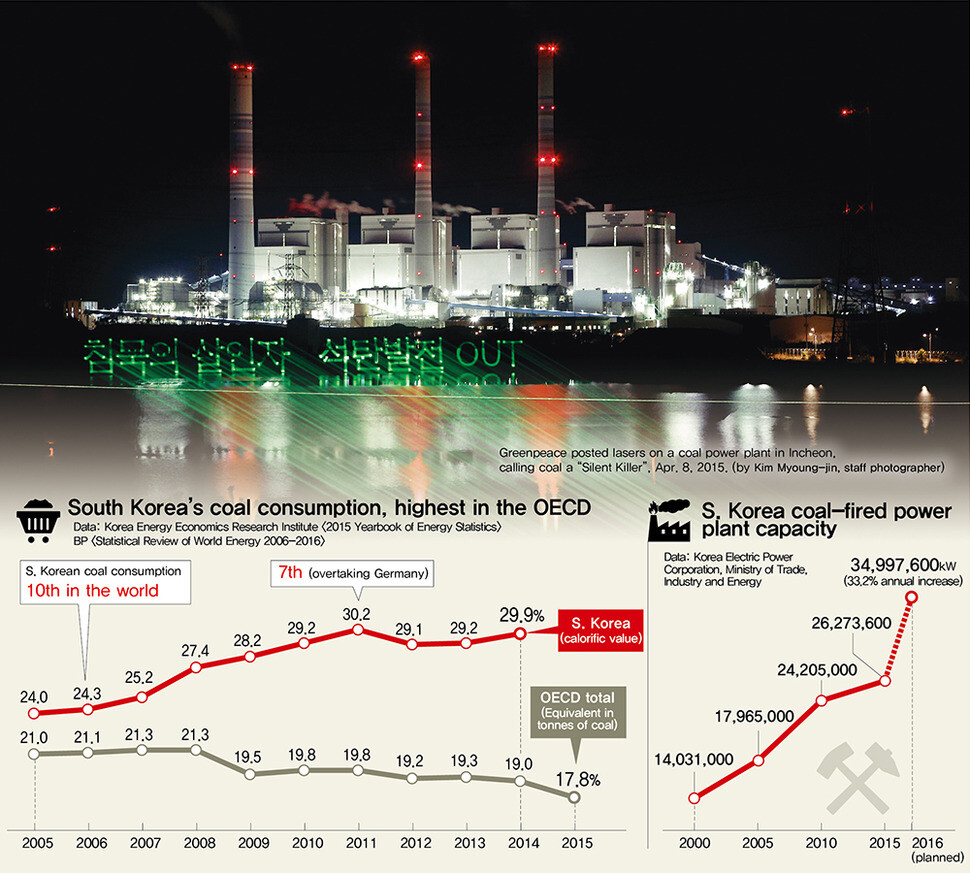

According to the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy’s 2015 annual energy statistics report, South Korea ranked 10th for commercial coal fuel consumption in 2006, at 54.8 million toe (tons of oil equivalent). In 2011, South Korea bypassed Germany, Poland and Australia to reach the number seven spot, with 83.6 million toe. While coal consumption in most advanced countries is decreasing or stagnant, these numbers are the result of a steady increase in the number of coal-fired power plants in South Korea. According to the IEA, a per-capita coal consumption of 2.29 tce (tons of coal equivalent) in 2014 means that South Korea has already moved past the US and China to become number five on the list.

When it comes to coal consumption for fuel, South Korea seems poised to catch up to Russia and South Africa for the number five position behind China, India, the US and Japan. Eleven new coal power plants, which will each burn millions of tons of coal per year, are scheduled to be completed by next year, increasing the country’s generation capacity by more than 33% from 26,274 megawatts at the end of 2015 to 34,998 megawatts. Even if the new power plants maintain an average rate of operation, the annual domestic coal use for the generation of power will balloon from approximately 81,558,000 tons last year to over 100 million tons.

Though the government announced on July 6 that it would shutter 10 aging coal-fired plants and that it would stop commissioning new coal-fired plants as part of measures to reduce airborne particulate matter, this hardly means that South Korea has joined the ranks of countries reducing their dependence on coal.

The government had already been planning to shut down or replace the fuel in four of the 10 plants, and the six whose shutdown was newly confirmed (No. 1 and No. 2 at Samcheonpo Coal Power Plant, No. 1 and No. 2 at Boryeong Coal Power Plant, and No. 1 and No. 2 at Honam Coal Power Plant) will not actually be shuttered until between 2020 and 2025. This means that the plants will operate for between four and nine more years, for a total operational lifespan ranging from 36 years on the low end (Samcheonpo) to 49 years on the high end (Honam).

Considering that Chungnam Seocheon Coal Power Plant (which the government already announced it would shut down in the seventh basic energy plan confirmed last year) is expected to remain in operation for 35 years altogether, the government’s announcement on July 6 looks less like a plan for an early phase-out of coal plants and more like a plan for extending their lifespan.

More coal-fired power plants being constructed than shut down

Furthermore, the government refuses to budge on its plan to build nine more coal plants by 2022. The nine power plants will have an installed capacity of 8,420MW – more than double the 3,345MW installed capacity of the 10 power plants the government intends to close.

Assuming that this 5,075MW addition in coal-fired power generation capacity operates at the efficiency of the 870MW Yeongheung Coal Plant No. 6, the most advanced plant currently in operation (as of 2015, producing 7,002,528MWh of electricity per 2,787,403 tons of coal input) the amount of coal that is used for power generation will increase by more than 16 million tons a year. This means that South Korea is a long way from becoming coal-free.

South Korea is actively involved in the construction of coal-fired plants not only at home but also in other countries. South Korea’s investment in the overseas coal industry by way of export credit agencies in 2014 amounted to US$7 billion, the most of any country in the OECD aside from Japan.

This is why South Korea is under fire from both domestic and international environmental groups for selling greenhouse gases and air pollution.

This is also why the board of directors of the Green Climate Fund – whose secretariat is located in South Korea – decided during a meeting on June 30 not to authorize the Export-Import Bank of Korea to carry out the fund’s projects and to distribute its money.

The number one reason that South Korea is ignoring the movement away from coal and keeps trying to increase its coal consumption is because coal is cheap.

Statistics for 2015 provided by the Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO) list the price for 1kWh of electricity purchased from power generating companies according to the type of generation: 62.61 won (US$0.05) for nuclear power, 71.41 won for bituminous coal, 105.99 won for wind power, 153.84 won for solar energy and 169.49 won for liquefied natural gas (LNG).

While nuclear power is even cheaper than bituminous coal, potent opposition to nuclear power makes the construction of coal-fueled power stations seem a rational choice. But coal’s price does not account for the cost of environmental damage and health problems caused by air pollution, including the particulate matter that has made headlines recently.

But greenhouse gases and particulate matter are not coal plants’ only problematic products. These plants also produce heavy metals and various other trace toxins that are harmful to the human body, though they receive scant attention in South Korea.

According to a study published by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2011 that laid the groundwork for the agency’s MATS (Mercury and Air Toxics Standards) regulations for coal plants, these plants are virtual heavy metal factories, churning out 50% of the mercury, 62% of the arsenic, 39% of the cadmium and 22% of the chrome among all US environmental emissions.

South Korea backpedaling on reduction of greenhouse emissionsIn South Korea, a survey of this sort has only been done for mercury. According to a report called “A Second Study on Mercury Emissions from Air Polluting Facilities,” which an industry and academic cooperative team of researchers at Yonsei University prepared for the Ministry of Environment in 2011, 27.19% of mercury emissions came from thermal power stations (97.6% of which were coal-fired).

In 2007, prestigious medical journal The Lancet published research concluding that, for every 1TWh of electricity generated, 24.5 people die prematurely and 225 people come down with serious diseases that require hospital care – and that assumes that the coal-fired plants are actually following emissions standards. Given South Korea’s 207.3TWh of electricity produced by burning coal in 2015, this implies that there were 5,078.9 premature deaths. But considering South Korea’s small territory and its high population density, the actual damage is most likely even greater than that.

A joint research project carried out last year by Greenpeace, the environmental advocacy group, and researchers from Harvard University predicted that fine particulate matter (PM2.5) produced by the 20 coal plants that are either under construction or being planned in South Korea will result in 1,020 premature deaths a year. This incalculable sacrifice is a cost that need not be paid if we used renewable energy.

Ahn Byeong-ok, director of the Institute for Climate Change Action, offered his thoughts on how much longer South Korea can afford to indulge in cheap coal.

“There are already a lot of places around the world that have reached grid parity – that is, where renewable energy costs about the same as coal-fired energy. With renewable energy getting cheaper at a rate that is faster than we expected, coal may start to lose its appeal,” Ahn said.

In a report published last month titled “The Power to Change: Solar and Wind Cost Reduction Potential to 2025,” the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) predicted that by 2025 the rapid development of renewable energy technology would push down the generation cost of onshore wind by 26%, offshore wind by 35%, and solar energy by 59% compared to last year’s rates. This means that a day will soon come when coal’s comparative price advantage will vanish, even without factoring in its environmental cost.

This could mean that South Korea’s excessive capacity in coal plants may become an albatross around its neck: the country might have to purchase power from polluting coal plants even after it costs more than clean electricity.

Since increasing efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions around the world necessarily implies less demand for coal, some experts think it will become even cheaper to buy coal in the future. But even if they are right, there is only so long that South Korea – one of the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitters, ranking seventh in carbon dioxide emissions – can keep reaping the windfall of disregarding the global community’s efforts to cut emissions.

“There’s a tendency for the international community to tolerate poor countries and developing countries when they use cheap coal despite their greenhouse gas emissions. But South Korea won’t be able to keep getting away with blending in with developing countries by turning cheap coal into cheap electricity,” said Lee Sang-hun, director of the Green Energy Strategy Institute.

By signing the Paris Agreement on climate change, South Korea promised the international community to reduce its greenhouse emissions by 37% of business-as-usual projections until 2030, as part of a new climate protocol that will launch after 2020. This regime will demand that the country’s target keep increasing.

The view shared by climate change experts is that, if the South Korean government moves ahead with its plans to increase the number of coal-fired plants, it will be effectively impossible to reach these targets. This means that, somewhere down the line, South Korea may find itself forced by international approbation to hurriedly “call off the party” and try to catch up to the coal-free campaign.

The future is not something that just happens; it is defined by each and every one of the choices that we make today. What future will South Korea choose to make?

By Kim Jeong-su, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 3After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 4US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 5[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 6[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 7Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 8Nearly 1 in 5 N. Korean defectors say they regret coming to S. Korea

- 9John Linton, descendant of US missionaries and naturalized Korean citizen, to lead PPP’s reform effo

- 10Strong dollar isn’t all that’s pushing won exchange rate into to 1,400 range