hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Rich/poor gap continues to widen

By Ryu Yi-geun, staff writer

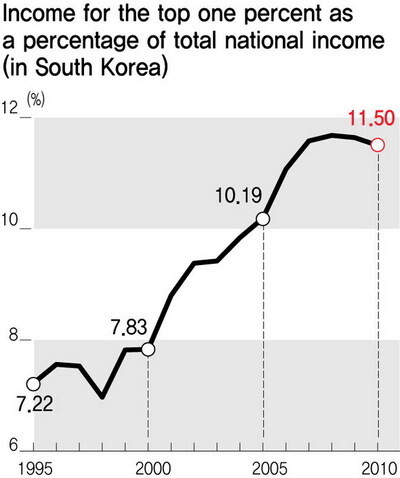

The percentage of total national income earned by the top 1% of South Koreans rose sharply in the 2000s, from just over 7% through the 1990s to 12% in 2010, according to a recent study.

The Hankyoreh obtained a copy of a report showing trends of income concentration in South Korea compared to other countries by Dongguk University economics professor and Naksungdae Institute of Economic Research director Kim Nak-nyun. In it, the percentage of total income in the hands of the top 1% was shown rising from 7.22% in 1955 and 6.97% in 1998 to 11.50% in 2010, after a peak of 11.68% in 2008.

Average per capita income for the top 1% was 195 million won (US$172,000) in 2010. The bulk of the earnings (65.1%) consisted of earned income, followed by business and real estate earnings (30.3%), dividends (2.5%), interest earnings (1.8%), and “other” (0.3%). Earned income constituted a smaller portion and business/real estate earnings a greater one compared to the average for all earners.

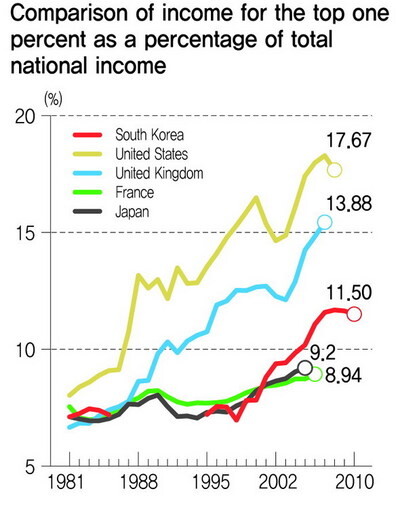

The concentration of wealth among the top 1% of earners crossed the 10% line in 1987 for the United States and 1993 for the United Kingdom. In Japan and France, it remained below 10% through the 2000s.

Kim‘s study involved a comparative analysis of National Tax Agency annual national statistics and Bank of Korea data on national accounts. The findings show a pattern of increasingly unequal wealth distribution in South Korea, the US, Japan, the UK, and France.

Kim explained that income inequality rose amid changes in the pay system. “We’ve seen the pay of the top earners soar to several times that of other earners while the number of jobs has failed to increase much since the foreign exchange crisis,” he said.

Chung-Ang University sociology professor Shin Kwang-young said, “This data provides a clear picture of how income inequality in South Korea is coming to resemble the US and UK.”

Kim’s report shows an average annual income of some 195 million won for the top 1% of earners, indicating a substantial distance between them and ordinary or self-employed workers.

Korea Institute for New Society researcher Yeo Gyeong-hun said that the self-employed had an average income of around 20 million won in 2009, with an average of 110 million won for health care and public health workers in this group.

“It looks as though doctors and pharmacists probably make up a large portion of the top 1%,” Yeo said.

No data exists to show precisely which people make up the top 1% of earners. They are presumed to consist for the most part of corporate owners and executives, as well as doctors, lawyers, patent agents, accountants, and other professionals.

After experiencing little change before then, the percentage of earnings for the top 1% rose precipitously after the foreign exchange crisis in 1998, when the South Korean economy experienced a major shock.

Few dispute that the foreign exchange crisis marked the beginning of this rapid concentration of South Korean wealth among the top 1%, but opinions vary on the causes.

Kim said the reason income distribution was more equal during the country’s period of rapid growth was because the fruits of growth were distributed more evenly throughout the population as employment opportunities become more abundant.

“Income concentration intensified with a decline in employment quality after the foreign exchange crisis, and an increase in service industries centering on the self-employed,” Kim explained.

Some analysts suggested that the concentration of economic power with large exporting companies contributed significantly to polarization.

“The added value produced by large exporters is not being distributed evenly,” said National Assembly Budget Office economic analyst Jang In-seong. “Instead, it’s mostly going to company owners and CEOs in the form of rising stock values and dividends.”

Even as the overall pie grows with greater corporate earnings, the workers are receiving a shrinking portion.

Other factors at play include a sharp rise in income for highly paid professionals and skilled workers in general, and an increase in bonuses and stock options for CEOs and executives at large companies. Meanwhile, income for low earners has failed to keep pace amid an increase in temporary positions owing to labor market flexibilization, coupled with an inadequate social safety net.

Some analysts contend the solution demands a more active role for the state. In a recent report titled “International Comparison of the Characteristics of the Ultra-High Income Class,” the Korea Institute of Public Finance, a national think tank, argued, “Because the rise in the percentage of income possessed by the uppermost class also means an increase in inequality, this necessitates a tax policy that prioritizes redistribution.”

South Korea ranks last among OECD nations welfare expenditures such as public pension payments. It spends one-eight as much as Northern European countries like Denmark and Sweden.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 2Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 3The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 4Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 5Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 6[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 7N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 8[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 9Up-and-coming Indonesian group StarBe spills what it learned during K-pop training in Seoul

- 10Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76